| Battle of the Wabash | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northwest Indian War, American Indian Wars | |||||||

Arthur St. Clair | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Western Confederacy | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

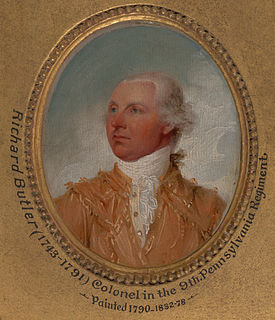

| Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, Buckongahelas | Arthur St. Clair, Richard Butler † William Darke | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,100 | 1,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 21 killed 40 wounded total: 61 | 632 soldiers killed or captured 264 soldiers wounded 24 workers killed, 13 workers wounded total: 933 (not including women and children) | ||||||

St. Clair's Defeat also known as the Battle of the Wabash, the Battle of Wabash River or the Battle of a Thousand Slain, [1] was a battle fought on November 4, 1791 in the Northwest Territory of the United States of America. The U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of Native Americans, as part of the Northwest Indian War. It was "the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military." [2] It was the largest victory ever won by Native Americans. [3]

The Northwest Territory in the United States was formed after the American Revolutionary War, and was known formally as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio. It was the initial post-colonial Territory of the United States and encompassed most of pre-war British colonial territory west of the Appalachian mountains north of the Ohio River. It included all the land west of Pennsylvania, northwest of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River below the Great Lakes. It spanned all or large parts of six eventual U.S. States. It was created as a Territory by the Northwest Ordinance July 13, 1787, reduced to Ohio, eastern Michigan and a sliver of southeastern Indiana with the formation of Indiana Territory July 4, 1800, and ceased to exist March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio, and the remainder attached to Indiana Territory.

The Western Confederacy, or Western Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States following the American Revolutionary War. The confederacy was also sometimes known as the Miami Confederacy, as many federal officials at the time overestimated the influence and numerical strength of the Miami tribe within the confederation. The confederacy, which had its roots in pan-tribal movements dating to the 1740s, came together in an attempt to resist the expansion of the United States, and the encroachment of American settlers, into the Northwest Territory after Great Britain ceded the region to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The resistance resulted in the Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), which ended with an American military victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

Native Americans, also known as American Indians, Indigenous Americans and other terms, are the indigenous peoples of the United States, except Hawaii. More than 570 federally recognized tribes live within the US, about half of which are associated with Indian reservations. The term "American Indian" excludes Native Hawaiians and some Alaska Natives, while "Native Americans" are American Indians, plus Alaska Natives of all ethnicities. The US Census does not include Native Hawaiians or Chamorro, instead being included in the Census grouping of "Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander".

Contents

- Background

- Command structure

- The campaign

- Battle

- Aftermath

- Native American response

- British response

- American response

- Popular culture

- Notes

- See also

- References

The natives were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). The war party numbered more than one thousand warriors, including a large number of Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph. The opposing force of about 1,000 Americans was led by General Arthur St. Clair. The forces of the American Indian confederacy attacked at dawn, taking St. Clair's men by surprise. Of the 1,000 officers and men that St. Clair led into battle, only 24 escaped unharmed. As a result, President George Washington forced St. Clair to resign his post and Congress initiated its first investigation of the executive branch. [4]

Little Turtle ,, was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader then in the Old Northwest," although he later signed several treaties ceding land, which caused him to lose his leader status during the battles which became a prelude to the War of 1812. In the 1790s, Mihšihkinaahkwa led a confederation of native warriors to several major victories against U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian Wars,sometimes called "Little Turtle's War", particularly St. Claires Defeat in 1791, wherein the confederation defeated General Arthur St. Clair, who lost 900 men in the most decisive loss by the U.S. Army against Native American forces.

Blue Jacket or Weyapiersenwah was a war chief of the Shawnee people, known for his militant defense of Shawnee lands in the Ohio Country. Perhaps the pre-eminent American Indian leader in the Northwest Indian War, in which a pantribal confederacy fought several battles with the nascent United States, he was an important predecessor of the famous Shawnee leader Tecumseh.

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking ethnic group indigenous to North America. In colonial times they were a semi-migratory Native American nation, primarily inhabiting areas of the Ohio Valley, extending from what became Ohio and Kentucky eastward to West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Western Maryland; south to Alabama and South Carolina; and westward to Indiana, and Illinois.