Service in the Northwest Territory

In the 1780s,many Americans wished to settle the "Old Northwest" as the Midwest was known at the time,which of course meant displacing the Indian tribes living there. [5] Supported by the British who still held fur-trading forts in the Old Northwest,the Indians of the Western Confederacy were resolved to oppose the Americans. [5] In 1784,the newly independent United States had almost no army,as the Continental Army had been disbanded with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. [6] In 1784,the entire United States Army comprised just 55 artillerymen at West Point and 25 more at Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh). For defense,the United States relied upon the state militias,who disliked fighting outside of their own states. [6] To enforce American claims upon the Old Northwest,on 3 June 1784,Congress called for a federal regiment,known as the First American Regiment,of about seven hundred men,to be supplied and paid for by Pennsylvania,New Jersey,New York and Connecticut. [6]

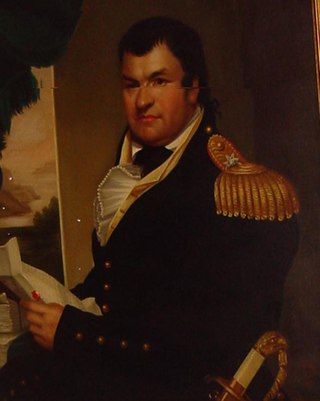

As the largest contingent (about 260 men) came from Pensylvania,the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was allowed to choose the commander of the regiment. Thomas Mifflin,a powerful Pennsylvania politician,successfully pushed for his friend Josiah Harmar to become commander. [6] Harmar was described as a political general with a fondness for alcohol who was only given the position due to his political connections. [7] Harmar's first task was to train the First American Regiment,imposing a rigorous training regime intended to turn the sons of farmers,unemployed urban laborers,and assorted adventurers into professional soldiers. [8] Harmar was known as a strict disciplinarian who would punish his soldiers harshly if their uniforms were dirty or rust appeared on their weapons. [8] Harmar reported to Congress in September 1784 that his emphasis upon Prussian-style drill and discipline was having results as "the troops begin to have a just idea of the noble profession of arms". [8] Shortly afterwards,Harmar was ordered to march to Fort Pitt for his regiment was needed to enforce American claims on the Northwest. [8] Harmar was not impressed with the people of Fort Pitt,writing that they "lived in dirty log cabins and were prone to find joy in liquor and fighting". [9]

As commander of the First American Regiment,Harmar was the senior officer in the United States Army from 1784 to 1791,commanding from Fort McIntosh. Initially,the First American Regiment was to be based in Fort Pitt,but as the Indian chiefs he was to negotiate with did not want to visit Fort Pitt,Harmar relocated his command to Fort McIntosh. [9] Harmar described Fort McIntosh when he found it as having been thoroughly looted by settlers heading for Kentucky,writing the settlers had "destroyed the gates,drawn all the Nails from the roofs,taken off the boards and plundered it of ever article". [9] Harmar was impressed with the richness of the land of the Northwest. In 1785,he wrote to a friend:"I wish you were here to view the beauties of Fort M'Intosh. What think you of pike of 24 lbs,a perch of 15 to 20 lbs,cat-fish of 40 lbs,bass,pickerel,sturgeon &c &c. You would certainly enjoy yourself." [6] Harmar also enjoyed the strawberries growing in the wild,writing:"The earth is most luxuriantly covered with them –we have them in such plenty that I am almost surfeited with them;the addition of fine rich cream is not lacking". [10] He also consumed huge quantities of wine,cognac,whiskey and rum with every meal. [11] In a letter to his patron Mifflin,Harmar stated that stories of "Venison,two or three inches deep cut of fat,turkey at once pence per pound,buffalo in abundance and catfish of one hundred pounds that are by no means exaggerated",going on to write that "cornfields,gardens &c,now appear in places which were lately the habitation of wild beasts. Such are the glories of industry." [11]

Harmar signed the Treaty of Fort McIntosh on 21 January 1785,the same year that he ordered the construction of Fort Harmar near what is now Marietta,Ohio. Harmar did not think the Treaty of Fort McIntosh that he had just signed with the Delaware,Ottawa,Chippewa,and Wyandot ceding what is now southeastern Ohio to the United States to be worth much,writing:"Between you and me,vain and ineffectual all treaties will be,until we take possession of the posts. One treaty held at Detroit would give dignity and consequence to the United States,and answer every purpose". [12]

Until the creation of the Northwest Territory in 1787,the Northwest had no government beyond the U.S. Army,and even after the creation of the Northwest Territory,the area was administered by the War Department for several more years. [12] At this time,hundreds of American settlers,anxious to acquire the rich lands beyond the Ohio River,had begun to illegally settle in the Old Northwest,and in March 1785,Harmar was ordered by Congress to evict the squatters as no land surveys had been performed yet nor had the U.S. government started the work of selling the land. [13] Harmar described the evictions as a painful process as his soldiers had to force the settlers off their newly build homesteads and in his letters to Congress,Harmar asked that the land be surveyed and sold before the entire Northwest was overrun by "lawless bands whose actions are a disgrace to human nature". [14] In May 1785,Thomas Hutchins was appointed Geographer of the United States by Congress and was ordered to go to the Northwest to survey all land of the land,starting with the Seven Ranges. [14] Harmar was ordered by Congress to provide protection for the land surveyors. [14] In September 1785,when Hutchins and his surveyors arrived,Harmar assured him that he "very safely repair with the Surveyors in the intersection of Pennsylvania with the Ohio". [14] In October 1785,Harmar founded Fort Harmar to provide protection for the surveyors. [15] At Fort Harmar,he supplied himself with much luxuries such as Windsor chairs,which led the American historian Wiley Sword to write that Harmar's "considerable urbanity may have rendered him somewhat suspect as an Indian fighter". [11] In November 1785,Harmar reported to Congress that the early arrival of winter together with the fact that soldiers who were guarding the surveyors from Indians and squatters were "barefoot and miserably off for clothing" had ended the surveying for that year. [15]

One Indian people who refused to sign a treaty giving up their lands was the Shawnee,and Harmar was ordered in October 1785 to advance to the Great Miami River in order to persuade the Shawnee to sign away their land. [12] At the time,Congress took the viewpoint that the Indians living in the Old Northwest had by supporting the British in the Revolutionary War forfeited their land,from which they were to be evicted from,and the land handed over to American settlers. [16] The Indians did not share this viewpoint that they were defeated peoples living on a land that rightfully belonged to the Americans,and many began to resist efforts to evict them.

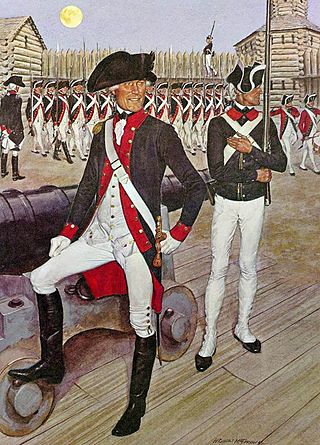

As a commander,Harmar was a stern martinet who was much influenced by Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben's manual Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States ,better known as the Blue Book for the Prussian-style training of American troops. [11] The American historian William Guthman noted:"Steuben's manual was aimed at combatting British and Hessian forces –not the backwoods guerilla fighting of the highly skilled American Indian warriors the regiment would eventually fight. Short-sightedness on the part of the military was the reason that no preparatory training in guerrilla warfare was ever imposed on the Army... no federal unit under Harmar or St. Clair was ever instructed in the frontiersmen's method of war". [11] Harmar doggedly insisted on Prussian-style training designed for the clash of regular forces in Central Europe,not the frontier style of irregular warfare in the forests of the Old Northwest that his men required. [10] The former Prussian officer Steuben held only a divisional command in the Continental Army,but as the chief trainer of the Continental Army,he had introduced Prussian drill and discipline into the American Army,and thanks to Steuben's training,the Continental Army became a formidable force. It is very unlikely that the Continental Army would have won the Revolutionary War without Steuben's training,and as a result,Steuben was greatly admired by many American officers. One of those officers was Harmar,who at the time of his death in 1813,was still insisting to anyone who would listen that all that was needed for victory was to follow the precepts laid down in Steuben's Blue Book. [11]

Harmar also supervised the construction of Fort Steuben near present-day Steubenville,Ohio. In June 1787,he reported to Congress that the Seven Ranges had been surveyed,and the white settlers could finally legally move in. [15] He was brevetted as a brigadier general in July 1787. [17] On 17 July 1787,Harmar visited Vincennes,at the time a mostly French-Canadian town,where he was welcomed by the "principle French inhabitants" and where he informed them that the area was now part of the United States. [18] The people of Vincennes' previous encounters with the Americans had been with the lawless Kentucky militia,who had not impressed them,which led Harmar in a letter to the people of Vincennes to tell them the men they met before were "not real Americans". [18] During his time at Vincennes,several Indian chiefs came to visit him,where Harmar sought to "impress upon them as much as possible the majesty of the United States" and the wish of the U.S government "to live in peace with them". [19] Harmar then visited Cahokia and Kaskaskia whose inhabitants had not seen any representatives of the U.S. government since the Revolutionary War,and who Harmar reported had shown "decent submission &respect" for the U.S. government. [20] Harmar was finally received at St. Louis by Major Francisco Cruzat of the Spanish Army where Harmar reported he was "politely entertained" while noting that the entire Spanish garrison at St. Louis numbered only 20 men. [20]

In April 1788,Harmar greeted Rufus Putnam of the Ohio Land Company,who had promoted "Putnam's Paradise" in New England,and he founded the village of Marietta next to Fort Harmar. [21] Harmar reported in June 1788 that between December 1787-June 1788 at least 6,000 settlers had passed through Fort Harmar on their way to found settlements beyond the Ohio river,writing "The Emigration is almost incredible". [22] At the new village of Marietta,Harmar celebrated the Fourth of July in 1788 with Putnam,having his regiment march down the street in a parade. [23] At Fort Harmar,he built a "commodious fine house...an elegant building for this wooden part of the world",where his wife and his son Charles joined him. [23]

As more and more settlers moved into the Northwest,more and more reports of violence between the settlers and the Indians reached Fort Harmar. [22] Harmar complained that the government was tardy with paying his men,to which he was informed that because fewer than the requisite nine states were represented in Congress because some states were boycotting Congress,it was impossible to pass a budget. [23] For this reason,Harmar welcomed the constitution of 1787,which replaced the Articles of Confederation,expressing the hope with a newly strong federal government that "Anarchy and Confusion will now leave and that a vigorous government will take its place". [24]

With low-level warfare in the Northwest between the Indians and the settlers now the norm,Harmar together with the governor of the Northwest Territory,General Arthur St. Clair started talks in January 1789 with Indian leaders representing the remaining Iroquois,the Ottawa,Chippewa,Wyandot,Potawatomi,Sauk,and Lenape peoples,where the Indians were informed that they could either sell their land for a set price or face war. [25] Both St. Clair and Harmar refused the Indian demand that no more white settlement be allowed beyond the Ohio River,and the resulting Treaty of Fort Harmar saw more land ceded to the United States. [25] None of the Indian peoples living on the Wabash River attended the conference having not been invited,and Harmar predicted that this would mean war with the Miami,the Shawnee and those Potawatomi living on the Wabash. [25] One of Harmar's aides called the Treaty of Fort Harmar a "farce" done to amuse Congress which had the notion the Northwest could be colonized peacefully and predicted the Western Confederacy would fight. [25]

He directed the construction in 1789 of Fort Washington on the Ohio River (located in modern-day Cincinnati),which was built to protect the southern settlements in the Northwest Territory. The fort was named in honor of President Washington. Harmar arrived at the fort on December 28,1789,and welcomed Governor St. Clair there three days later.

By August 1789,enough reports had reached President Washington of widespread violence in the Northwest that he argued that the situation required the "immediate intervention of the General Government". [25]

Harmar's relations with his superiors were not good. [26] President Washington's War Secretary,Henry Knox,was a firm believer that the nation's first line of defense should be the state militias and was hostile to the very idea of a standing army. [26] Knox was a Revolutionary War veteran with a distinguished record,but as War Secretary,he proved to be an unsavory character whose principal interest was engaging in land speculation. [26] As Secretary of War,Knox confiscated land belonging to the Indians,and then sold it at rock-bottom prices to land companies (in which he happened to be a shareholder),which then marked up the land and sold it to American settlers. [26] At the time,the rules on conflicts of interest did not exist and these transactions were legal,through widely viewed as unethical and morally dishonest. [26] To make good these land sales required that the Indians living on the land that Knox was planning to sell be displaced,which made Knox one of the leading hawks in New York (which at the time was the U.S. capital),forever urging that all of the Indians be cleared off the land,so he could sell it all. [26] At the same time,Knox's dislike of the U.S. Army and his preference for using the state militias made the task of displacing the Indians more difficult than it otherwise would have been. [26] The American journalist James Perry wrote that "even Harmar" saw the "danger" of Washington's and Knox's attempts to fight war in the Northwest on the cheap by mobilizing the state militias of Pennsylvania and Kentucky instead of raising more U.S. Army troops. [26]

For his part,Harmar wrote:"No person can hold a more contemptible opinion of the militia in general than I do... It is lamentable... that the government is so feeble as not to afford three or four regiments of national troops properly organized that would soon settle the business with these perfidious villains upon the Wabash." [27] One of Harmar's subordinates,Major Ebenezer Denny,called the Kentucky militia out to assist with conquering the Old Northwest "raw and unused to the gun or the woods;indeed,many are without guns". [27] Harmar complained that the men of the Pennsylvania militia were "hardly able to bear arms - such as old,infirm men and young boys". [27] There were so many sickly,underage and old men in the Pennsylvania contingent sent out to serve under him that Harmar refused to commit them to action in the coming campaign. [27] Very few men wanted to serve in the militia,let alone in a dangerous expedition to the frontier of the Northwest,and so the militiamen sent to serve under Harmar tended not to be the best caliber of troops. [27] The American historian Michael S. Warner described the Kentucky and Pennsylvania militiamen as lacking "discipline,experience and in many cases even muskets". [28]

Campaign against the Miamis

In 1790, Harmar was sent on expeditions against Native Americans and the remaining British in the Northwest Territory. The British who held fur trading forts in the Northwest kept the Indians well supplied with guns and ammunition to keep the Americans out of the area. [6] Furthermore, the Montreal-based North West Company had taken over the old French fur trading routes together with the services of the French-Canadian Voyageurs , and thus had a vested interest in keeping the Northwest for the Indians who sold them the furs that were the source of such profit to them. Knox in a letter on 7 June 1790 ordered Harmar "to extirpate, utterly, if possible, the said Indian banditti". [27] At the same time, Knox sent a letter to Major Patrick Murray commanding the British garrison at Fort Detroit, telling him of the coming expedition. [29] The British response was to inform all of the Indian tribes of the expedition and to release a huge number of rifles and ammunition to the Indians. [29]

Knox, who stood to greatly profit if the Indians were cleared out of the Northwest, seemed to have ordered the expedition in a moment of rage at the obstinate resistance of the Miami, Shawnee and Potawatomi peoples who resisted his attempts to evict them, leading Warnar to comment that anger is not the best emotion when making command decisions. [30] Knox, in his letters to Harmar, repeatedly advised him to move fast, strike hard, and avoid drinking, saying that sober generals were victorious generals. The frequency of the last warning indicated that Knox did not have much confidence in Harmar, which led Warner to question just why he was given the command in the first place given the evident doubts that both Washington and Knox had about him. [30]

Preparations

Harmar's reputation had preceded him, because of which, many of the militiamen from Kentucky and Pennsylvania were "substitutes" (men paid to take the place of the men who were called to serve) and many of the experienced Indian fighters did not want to serve under Harmar. [31] The state militias were paid $3/day, which led Warner to note that for a typical farmer, this would mean neglecting his farm and leaving his family and friends behind to go on a dangerous mission on the Northwest frontier for 60 days, during which time he would earn a total of $60 for his troubles. [31] Most farmers would not willingly go if called up, and when called, many farmers hired substitutes, who came from the lowest elements in American society in their place. [31] Warner wrote that the soldiers of the U.S. Army were also recruited from the lowest elements of American society, but they served on a long-term basis and were well trained. [31] By contrast, Harmar had only two weeks to train his Kentucky militia and only a few days to train the Pennsylvania militia before departing on 1 October 1790. [31]

Harmar was to take 1,300 militiamen and 353 regulars to sack and destroy Kekionga (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana), the capital of the Miami Indians, while the Kentucky militia under Major Jean François Hamtramck was to create a distraction by burning down villages on the Wabash river. [29] Before going out on his expedition, Harmar was faced with quarrels among the various militia commanders as to who was to command whom, with Colonel James Trotter and Colonel John Hardin of the Kentucky militia openly feuding with one another. [29] Shortly before the expedition began in September 1790, Knox sent Harmar a letter accusing him of alcoholism, writing he had heard rumors that "you are too apt to indulge yourself in a convivial glass" to the extent that Harmar's "self-possession" was now in doubt. [32]

Campaign

Harmar, who was much influenced by the Blue Book for the Prussian style training of troops, marched his men out in a formation that would have been appropriate for Central Europe or the Atlantic seaboard of the United States, but not in the wildness of the Northwest. This led to his men getting bogged down, averaging about ten miles per day. [32] Harmar had hoped to reach Kekionga in order to capture the British and French-Canadian fur traders, whom he called the "real villains" of the war because they provided the Miami with guns and ammunition, but his sluggish advance precluded this. [28] Much to Harmar's surprise, Little Turtle refused to give battle, instead retreating and everywhere the Indians burned their villages. [33] On 13 October 1790, Harmar sent out a light company commanded by Hardin to hunt down the retreating Indians. [33] The arrogant Harmar, who held the Indians in complete contempt for racial reasons, believed that the Indians refused to engage him in battle because they were cowards, and that he would soon win the war without even fighting. [33]

After getting lost in the woods and failing to find any Indians, Hardin finally reached Kekionga on 15 October to discover the town was empty and burning. [33] The Kentucky militia promptly spread out far and wide as the militiamen went looking for loot to take home with them. [33] Harmar reached Kekionga on 17 October 1790, and wrote to President Washington that same day to tell him that he had won the war without firing a shot. [33] Harmar got his first inkling of trouble later that night, when the Miami staged a raid that stole about hundred packhorses and cavalry horses, which greatly reduced the mobility of Harmar's force. [33]

The next day, Harmar ordered Trotter to take about 300 Kentucky militiamen out to hunt down the Miami hiding in the woods with the stolen horses. [33] Trotter marched into the woods, encountered one Indian riding a horse whom his party promptly killed, and then another Indian whom they chased and killed. [34] Afterwards, Trotter received reports from a scout that he had seen at least 50 Miami out in the woods, which caused Trotter to immediately return to the camp. [35] Hardin, who loathed Trotter, denounced him openly as a rank coward, and told anyone who would listen that he would have stayed and fought the Miami if he was in Trotter's position. [35] Denny wrote in his diary that Hardin "showed displeasure at Trotter's return without executing the orders he had received, and desired the General to give him command of the detachment". [35] Harmar sent Hardin out early the next morning, 19 October, with 180 men, including 30 U.S. Army soldiers. [35] Denny wrote in his diary: "I saw that the men moved off with great reluctance, and am satisfied that when three miles from the camp he [Hardin] had not more than two-thirds of his command; they dropped out of the ranks and returned to the camp." [35] Hardin managed to lose one company of Kentucky militia under Captain William Faulkner, which was left behind accidentally after his men stopped for a break. This led him to send Major James Fontaine and his cavalry to go find Faulkner to tell him to rejoin the main force. [35] In the meantime, Hardin stretched a column out over half a mile in the woods with 30 U.S. Army troops led by Captain John Armstrong in the lead. [35] At a meadow close to the Eel River, Hardin discovered the ground was covered with countless trinkets, with a fire burning at one end. [35] The Kentucky militiamen immediately dispersed to collect as much as of the loot as they could, despite warnings from Armstrong to stay in formation. [35] Once the militiamen were spread out far and wide, Little Turtle, who had been watching from a hill, gave the order for the Indians hiding in the woods to open fire on the Americans. [35] Denny who questioned survivors wrote in his diary: "The Indians commenced a fire at the distance of 150 yards and advanced. The greatest number of militia fled without firing a shot; the 30 regulars that were part of the detachment stood and were cut to pieces". [36] While the Kentucky militia fled in terror, shouting that it was every man for himself, the U.S. Army regulars joined by nine brave militiamen stood their ground, and returned fire at the unseen enemy in the woods. [36] While the U.S. Army soldiers were reloading their muskets, a force of Miami, Shawnee and Potawatomi Indians emerged from the woods, armed with tomahawks. [36]

In the ensuring battle, with the bayonets of the Americans vs. the tomahawks of the Indians, the Americans fought bravely, but were annihilated with nearly every American in the meadow being cut down and killed. [36] Armstrong, who escaped into a swamp and feigned death, reported that "They fought and died hard". [36] Afterwards, the bodies of the Americans slain on the field were all scalped and hacked to pieces as was normal with the Indians. [36] As the rest of the Kentucky militiamen were running away, they ran into Fontaine and Faulkner coming up to join the main force, leading one militiaman to shout: "For God's sake, retreat! You will all be killed. There are Indians enough to eat you all up!". [36] Harmar was deeply shocked when Hardin and what was left of his force stumbled into the camp to report their defeat. [36] A furious Armstrong arrived at the camp the next day, cursing the "dastardly" behavior of the Kentucky militia and vowed never to fight with them again. [36] Harmar for his part threatened to bring down cannon fire on the Kentucky militia if he should ever see them retreating back to camp in disorder and defeat again. [36] Unknown to Harmar, his camp was being closely watched by the Indians, who were well armed with British muskets, but at a war council, it was decided that it would cause the lives of too many men if they tried to attack the American camp. [37]

On 20 October, Denny wrote in his diary that: "The army all engaged burning and destroying everything that could be of use: corn, beans, pumpkins, stacks of hay, fencing and cabins, &c". [36] Despite Hardin's defeat, Harmar believed he inflicted enough damage on the crops around Kekionga to impair the ability of the Miami to resist the Americans. [38] On 21 October, Harmar ordered his men to return to Fort Washington, much to the general relief of his men as by now the majority of the Americans were highly nervous to be out in the wilderness surrounded by hostile Indians. [39] After leaving Kekionga, Hardin suggested to Harmar that the Americans return to Kekionga to surprise the Miami who he expected would now come out of the woods to dig up their buried possessions. [39] Hamar initially rejected this suggestion, but Hardin insisted that the "honor" of the Kentucky militia demanded such a gesture; it is likely that Hardin was more concerned with his reputation after the inglorious performance of the militiamen in the battle by the Eel River, and was seeking a personal triumph. [37] Harmar finally agreed and in Denny's words "ordered out four hundred choice men, to be under the command of Major John Wyllys, to return to the towns, intending to surprise any parities that might be assembled there". [39] Major Wyllys in his last letter complained: "We are about agoing forth to war in this part of the world. I expect to have not a very agreeable campaign... Tis probable the Indians will fight us in earnest, the greater part of our force will consist of militia; therefore there is some reason to apprehend trouble." [39]

Harmar's Defeat

Harmar's force of Federal troops and militia from Pennsylvania and Kentucky were badly defeated by a tribal coalition led by Little Turtle, in an engagement known as "Harmar's Defeat", "the Battle of the Maumee", "the Battle of Kekionga", or "the Battle of the Miami Towns". Under the sky free of clouds and a full moon, Harmar sent out 60 U.S. Army soldiers and 340 militiamen under Wyllys with Hardin in second in command on the evening of October 21 back to Kekionga. [39]

The American force was divided into three with Major Horatio Hall to lead 150 Kentucky militiamen across the St. Mary's River to strike from the east while Major James McMillian of the Kentucky militia would attack from the west while Wyllys and the U.S. Army would strike frontally at Kekionga. [39] October 22 was a warm, sunny October day and the mood among the American forces was an upbeat one at the beginning of the day. [40] It was known that the Indians would usually avoid combat except on the most advantageous terms with the only exception being when their women and children were in danger, which would force the Indian warriors to stand and fight, and where superior firepower would overwhelm them. [41] It would be believed when the Indian women and children emerged from hiding in the woods to return to Kekionga that this would force Little Turtle to finally engage in battle. [42] Warner described the concept behind the plan as sound, but noted its execution left too much unplanned with for example no co-ordination between the three wings advancing on Kekionga, no thought paid to how the Americans were to cross into dense forest without being noticed by Indian scouts and no contingency plans if surprise was lost. [42]

The Kentucky militia under Hall and McMillian opened fire with everything they had when they both ran into small parties of Indians, instead of using their knives to kill them, thereby alerting the Indians to the American presence. [43] At the same time, the militiamen sent out to pursue the Indians who were fleeing down the St. Joseph's River, leaving Wyllys to lead his attack unsupported. [43] As the militiamen broke up into small groups to pursue the retreating Indians, in effect McMiillian's command had disintegrated. [44] One officer testifying at Harmar's court-martial in 1791 stated the shooting caused Indian women and children to go "flying in all directions" from Kekionga, and stated in his opinion the attack should have been abandoned as it both alerted the Indians and by causing the women and children to flee, ensured the Indians would not stand and fight in the open as they had been hoping. [42]

Little Turtle concentrated his main force at a ford in the Maumee River, where they lay waiting to ambush the Americans. [43] As the Americans were crossing the Maumee, one American, Private John Smith, later recalled that he saw "the opposite riverbank erupt in sheets of flame. Horse and riders were struck down as if by some whirlwind force." [43] Soon, the Maumee ran red with American blood, which led Jean Baptiste Richardville, a half-French, half-Miami chief, to later remark that he could have walked against the Maumee dry-footed as the river was clogged with American bodies. [43] Major Fontaine of the U.S. cavalry drew his sword and charged forward at the opposite bank, shouting "Stick with me!". [43] Upon reaching the banks, all of the Americans were cut down by Indian fire and Fontaine himself was badly wounded. [43] He later bled to death. Hearing the shooting, McMillian and his militiamen came up and forded the Maumee, intending to out-flank Little Turtle. [43]

At that point, the Indians departed in good order, with the Americans in hot pursuit. [43] The Indians went past the ruins of Kekionga and headed towards the St. Joseph's River. [43] The Kentucky militiamen led the pursuit, giving enthusiastic war whoops while Wyllys led the U.S. Army regulars behind them. [43] The Americans believed that Little Turtle was retreating, and failed to recognize that he had merely laid another ambush. [43]

Upon entering spread out helter-skelter in a cornfield, the Americans were astonished to hear what one veteran later recalled was a "hideous yell" as a huge number of Miami emerged from the underbrush. [43] In the "Battle of the Pumpkin Field", the Americans fired off one disorganized volley before they were forced to engage in desperate hand-to-hand fighting with their steel bayonets, swords and knives against the tomahawks, spears and knives of the Miami. [45] The "Battle of the Pumpkin Field" which saw the Indians engage in hand-to-hand combat with the Americans was unusual as normally the Indians preferred to avoid this type of combat. [46] Wyllys together with 50 U.S. Army soldiers and 68 militiamen all fell on the field, and their bodies were all scalped. [45] The Indians called the field a "pumpkin field" not because they were pumpkins growing in it, but rather because the bloody heads of the Americans lying out on the field reminded them of pumpkins.

One of the survivors was Hardin, who upon reaching Harmar's camp reported that the Kentucky militia had fought "charmingly" and claimed he had won a great victory. [45] Harmar considered marching out, but soon learned of the terrible defeat. [45] Harmar first learned of the defeat at about 11 am, when a horsemen rode in to report. [47] Harmar ordered Major James Ray to head out with some volunteers, but only 30 men volunteered, and he turned back only marching three miles. Harmar decided to retreat without making any effort to retrieve and bury the American dead, which was contrary to the normal practice in the U.S. Army. [47] Little Turtle could have finished off Harmar's force, which was saved only by a lunar eclipse, which the Indians regarded as a bad omen. [45] Harmar complained that the militia was "ungovernable" and close to mutiny, ordering that his U.S. Army regulars keep fixed bayonets on the militia to keep them marching in formation. [45]

Aftermath

When Harmar reached Fort Washington on 3 November 1790, American public opinion was outraged to learn of his defeat. [45] Upon returning, Harmar reported that he won a great victory to Knox, but the truth soon came out with militiamen giving interviews to the press accusing Harmar of alcoholism, cowardice and incompetence. [47] The fact that Harmar had never exposed himself to fire led to rumours appearing in the newspapers that he had spent the campaign drunk in his tent. [45] When the news reached New York, President Washington wrote to a friend: "I expected little from the moment I heard he was a drunkard". [45] Warner wrote the expedition was in fact poorly planned as its aim was to "chastise" the Indians of the Northwest by burning down their crops and homes without necessarily bringing Little Turtle to battle, through Harmar was do so if possible; the ambiguity on this point helps to explain Harmar's confusion about what he was supposed to do. [30]

Warner argued that, though Harmar did not have the best troops under his command, it was his lack of familiarity with frontier warfare caused him to make mistakes. In particular, Harmar should had known that the Indians preferred model of war was the ambush, and that the battle by the Eel river could have been avoided as Harmar should have known that Little Turtle would never engage his forces in the open. [48] The fact that Harmar did not attempt to return to bury the men slain by the Eel river was disastrous for morale as it persuaded his men that he was both a coward and indifferent to their lives. [49] Harmar's refusal to bury the American dead was something that the newspapers kept returning to, and gave him such a reputation for cowardice as to finish off his career. [50] The American dead of Kekionga were not finally buried until 1794 when General "Mad Anthony" Wayne finally defeated Little Turtle.

In the national rage caused by the debacle, bashing Harmar become a favorite pastime of the newspapers, but Perry wrote that Harmar was a scapegoat, and the ultimate responsibility rested with President Washington. [45] Perry wrote:

Harmar, in fact, became something of a scapegoat. Washington was just as culpable. He could have insisted on a more experienced, more able officer to lead the expedition. He didn't. He could have demanded the troops be trained in frontier fighting, for he, more than anyone else, knew all about that. He didn't. He could, in fact, have done his best to build a decent little army for a nasty little war. He didn't do that, either. And now he made an even bigger blunder. He named Arthur St. Clair, governor of the territory, as Harmar's replacement, with the rank of major general, and asked him to try again. Harmar was a calamity; St. Clair would be a catastrophe. [51]

Consequently, Harmar was relieved of command and replaced by General Arthur St. Clair, who subsequently suffered, in 1791, an even greater defeat than Harmar had.

Court martial

Harmar was subsequently court-martialed, at his own request, on various charges of negligence, and exonerated by a court of inquiry. [52] Harmar had a run-in with fellow soldier John Robert Shaw, who wrote about the general in his John Robert Shaw: An Autobiography of Thirty Years 1777–1807. [53]