Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity. When the cause of the convection is unspecified, convection due to the effects of thermal expansion and buoyancy can be assumed. Convection may also take place in soft solids or mixtures where particles can flow.

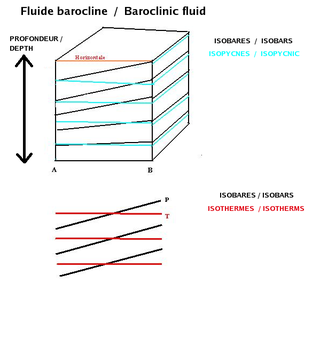

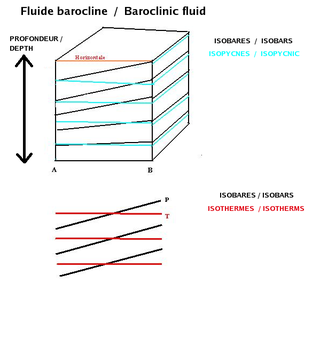

In fluid dynamics, the baroclinity of a stratified fluid is a measure of how misaligned the gradient of pressure is from the gradient of density in a fluid. In meteorology a baroclinic flow is one in which the density depends on both temperature and pressure. A simpler case, barotropic flow, allows for density dependence only on pressure, so that the curl of the pressure-gradient force vanishes.

In fluid dynamics, a convection cell is the phenomenon that occurs when density differences exist within a body of liquid or gas. These density differences result in rising and/or falling convection currents, which are the key characteristics of a convection cell. When a volume of fluid is heated, it expands and becomes less dense and thus more buoyant than the surrounding fluid. The colder, denser part of the fluid descends to settle below the warmer, less-dense fluid, and this causes the warmer fluid to rise. Such movement is called convection, and the moving body of liquid is referred to as a convection cell. This particular type of convection, where a horizontal layer of fluid is heated from below, is known as Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Convection usually requires a gravitational field, but in microgravity experiments, thermal convection has been observed without gravitational effects.

Equivalent potential temperature, commonly referred to as theta-e, is a quantity that is conserved during changes to an air parcel's pressure, even if water vapor condenses during that pressure change. It is therefore more conserved than the ordinary potential temperature, which remains constant only for unsaturated vertical motions.

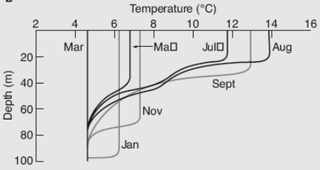

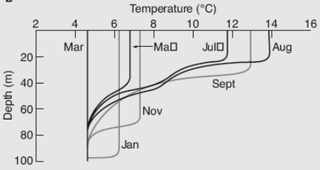

A thermocline is a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid with a high gradient of distinct temperature differences associated with depth. In the ocean, the thermocline divides the upper mixed layer from the calm deep water below.

A pycnocline is the cline or layer where the density gradient is greatest within a body of water. An ocean current is generated by the forces such as breaking waves, temperature and salinity differences, wind, Coriolis effect, and tides caused by the gravitational pull of celestial bodies. In addition, the physical properties in a pycnocline driven by density gradients also affect the flows and vertical profiles in the ocean. These changes can be connected to the transport of heat, salt, and nutrients through the ocean, and the pycnocline diffusion controls upwelling.

The potential temperature of a parcel of fluid at pressure is the temperature that the parcel would attain if adiabatically brought to a standard reference pressure , usually 1,000 hPa (1,000 mb). The potential temperature is denoted and, for a gas well-approximated as ideal, is given by

In atmospheric dynamics, oceanography, asteroseismology and geophysics, the Brunt–Väisälä frequency, or buoyancy frequency, is a measure of the stability of a fluid to vertical displacements such as those caused by convection. More precisely it is the frequency at which a vertically displaced parcel will oscillate within a statically stable environment. It is named after David Brunt and Vilho Väisälä. It can be used as a measure of atmospheric stratification.

Isopycnals are layers within the ocean that are stratified based on their densities and can be shown as a line connecting points of a specific density or potential density on a graph. Isopycnals are often displayed graphically to help visualize "layers" of the water in the ocean or gases in the atmosphere in a similar manner to how contour lines are used in topographic maps to help visualize topography.

Ocean stratification is the natural separation of an ocean's water into horizontal layers by density. This is generally stable stratification, because warm water floats on top of cold water, and heating is mostly from the sun, which reinforces that arrangement. Stratification is reduced by wind-forced mechanical mixing, but reinforced by convection. Stratification occurs in all ocean basins and also in other water bodies. Stratified layers are a barrier to the mixing of water, which impacts the exchange of heat, carbon, oxygen and other nutrients. The surface mixed layer is the uppermost layer in the ocean and is well mixed by mechanical (wind) and thermal (convection) effects. Climate change is causing the upper ocean stratification to increase.

The oceanic or limnological mixed layer is a layer in which active turbulence has homogenized some range of depths. The surface mixed layer is a layer where this turbulence is generated by winds, surface heat fluxes, or processes such as evaporation or sea ice formation which result in an increase in salinity. The atmospheric mixed layer is a zone having nearly constant potential temperature and specific humidity with height. The depth of the atmospheric mixed layer is known as the mixing height. Turbulence typically plays a role in the formation of fluid mixed layers.

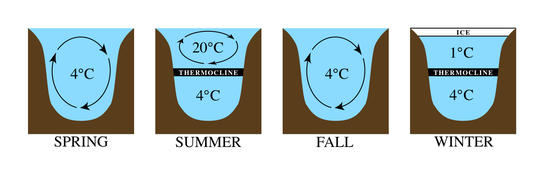

A dimictic lake is a body of freshwater whose difference in temperature between surface and bottom layers becomes negligible twice per year, allowing all strata of the lake's water to circulate vertically. All dimictic lakes are also considered holomictic, a category which includes all lakes which mix one or more times per year. During winter, dimictic lakes are covered by a layer of ice, creating a cold layer at the surface, a slightly warmer layer beneath the ice, and a still-warmer unfrozen bottom layer, while during summer, the same temperature-derived density differences separate the warm surface waters, from the colder bottom waters. In the spring and fall, these temperature differences briefly disappear, and the body of water overturns and circulates from top to bottom. Such lakes are common in mid-latitude regions with temperate climates.

Atmospheric instability is a condition where the Earth's atmosphere is considered to be unstable and as a result local weather is highly variable through distance and time. Atmospheric instability encourages vertical motion, which is directly correlated to different types of weather systems and their severity. For example, under unstable conditions, a lifted parcel of air will find cooler and denser surrounding air, making the parcel prone to further ascent, in a positive feedback loop.

In fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic stability is the field which analyses the stability and the onset of instability of fluid flows. The study of hydrodynamic stability aims to find out if a given flow is stable or unstable, and if so, how these instabilities will cause the development of turbulence. The foundations of hydrodynamic stability, both theoretical and experimental, were laid most notably by Helmholtz, Kelvin, Rayleigh and Reynolds during the nineteenth century. These foundations have given many useful tools to study hydrodynamic stability. These include Reynolds number, the Euler equations, and the Navier–Stokes equations. When studying flow stability it is useful to understand more simplistic systems, e.g. incompressible and inviscid fluids which can then be developed further onto more complex flows. Since the 1980s, more computational methods are being used to model and analyse the more complex flows.

Double diffusive convection is a fluid dynamics phenomenon that describes a form of convection driven by two different density gradients, which have different rates of diffusion.

Geophysical fluid dynamics, in its broadest meaning, refers to the fluid dynamics of naturally occurring flows, such as lava flows, oceans, and planetary atmospheres, on Earth and other planets.

The flow in many fluids varies with density and depends upon gravity. The fluid with lower density is always above the fluid with higher density. Stratified flows are very common such as the Earth's ocean and its atmosphere.

Stratification in water is the formation in a body of water of relatively distinct and stable layers by density. It occurs in all water bodies where there is stable density variation with depth. Stratification is a barrier to the vertical mixing of water, which affects the exchange of heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients. Wind-driven upwelling and downwelling of open water can induce mixing of different layers through the stratification, and force the rise of denser cold, nutrient-rich, or saline water and the sinking of lighter warm or fresher water, respectively. Layers are based on water density: denser water remains below less dense water in stable stratification in the absence of forced mixing.

The Turner angleTu, introduced by Ruddick(1983) and named after J. Stewart Turner, is a parameter used to describe the local stability of an inviscid water column as it undergoes double-diffusive convection. The temperature and salinity attributes, which generally determine the water density, both respond to the water vertical structure. By putting these two variables in orthogonal coordinates, the angle with the axis can indicate the importance of the two in stability. Turner angle is defined as:

Open ocean convection is a process in which the mesoscale ocean circulation and large, strong winds mix layers of water at different depths. Fresher water lying over the saltier or warmer over the colder leads to the stratification of water, or its separation into layers. Strong winds cause evaporation, so the ocean surface cools, weakening the stratification. As a result, the surface waters are overturned and sink while the "warmer" waters rise to the surface, starting the process of convection. This process has a crucial role in the formation of both bottom and intermediate water and in the large-scale thermohaline circulation, which largely determines global climate. It is also an important phenomena that controls the intensity of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).