The deuterocanonical books, meaning "Of, pertaining to, or constituting a second canon," collectively known as the Deuterocanon (DC), are certain books and passages considered to be canonical books of the Old Testament by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Church, and the Church of the East. In contrast, modern Rabbinic Judaism and Protestants regard the DC as Apocrypha.

The Epistle of James is a general epistle and one of the 21 epistles in the New Testament. It was written originally in Koine Greek.

The Epistle to the Hebrews is one of the books of the New Testament.

The Epistle to the Philippians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and Timothy is named with him as co-author or co-sender. The letter is addressed to the Christian church in Philippi. Paul, Timothy, Silas first visited Philippi in Greece (Macedonia) during Paul's second missionary journey from Antioch, which occurred between approximately 50 and 52 AD. In the account of his visit in the Acts of the Apostles, Paul and Silas are accused of "disturbing the city".

The Epistle to the Colossians is the twelfth book of the New Testament. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately 100 miles (160 km) from Ephesus in Asia Minor.

Our Lady of La Salette is a Marian apparition reported by two French children, Maximin Giraud and Mélanie Calvat, to have occurred at La Salette-Fallavaux, France, in 1846.

The Nazarenes were an early Jewish Christian sect in first-century Judaism. The first use of the term is found in the Acts of the Apostles of the New Testament, where Paul the Apostle is accused of being a ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes before the Roman procurator Antonius Felix at Caesarea Maritima by Tertullus. At that time, the term simply designated followers of Jesus of Nazareth, as the Hebrew term נוֹצְרִי, and the Arabic term نَصْرَانِي, still do.

Pseudepigrapha are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the work is falsely attributed is often prefixed with the particle "pseudo-", such as for example "pseudo-Aristotle" or "pseudo-Dionysius": these terms refer to the anonymous authors of works falsely attributed to Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, respectively.

The New Testament apocrypha are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

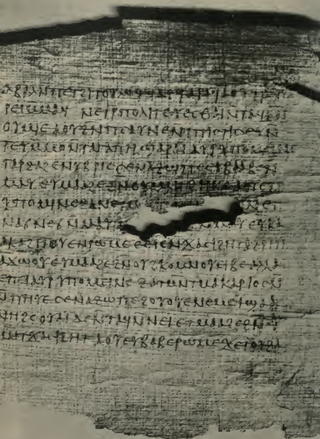

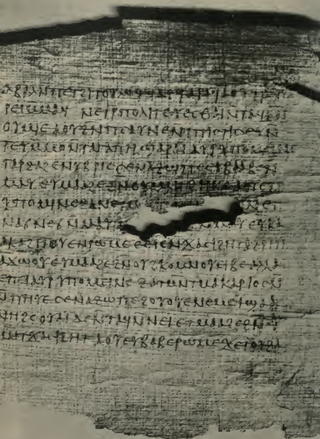

The Third Epistle to the Corinthians is an early Christian text written by an unknown author claiming to be Paul the Apostle. It is also found in the Acts of Paul, and was framed as Paul's response to a letter of the Corinthians to Paul. The earliest extant copy is Papyrus Bodmer X, dating to the third century. Originally written in Koine Greek, the letter survives in Greek, Coptic, Latin, and Armenian manuscripts.

The Epistle of the Apostles is a work of New Testament apocrypha. Despite its name, it is more a gospel or an apocalypse than an epistle. The work takes the form of an open letter purportedly from the remaining eleven apostles describing key events of the life of Jesus, followed by a dialogue between the resurrected Jesus and the apostles where Jesus reveals apocalyptic secrets of reality and the future. It is 51 chapters long. The epistle was likely written in the 2nd century CE in Koine Greek, but was lost for many centuries. A partial Coptic language manuscript was discovered in 1895, a more complete Ethiopic language manuscript was published in 1913, and a full Coptic-Ethiopic-German edition was published in 1919.

The Letter of Jeremiah, also known as the Epistle of Jeremiah, is a deuterocanonical book of the Old Testament; this letter is attributed to Jeremiah and addressed to the Jews who were about to be carried away as captives to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. It is included in Catholic Church bibles as the final chapter of the Book of Baruch. It is also included in Orthodox bibles as a separate book, as well as in the Apocrypha of the Authorized Version.

In Catholicism, the Lord's Day refers to Sunday, the principal day of communal worship. It is the first day of the week in the Hebrew calendar and traditional Christian calendars, with the exception of European (workweek) calendars. It is observed by most Christians as the weekly memorial of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who is said to have been raised from the dead early on the first day of the week. The phrase appears only once in Rev. 1:10 of the New Testament.

The Lost Books of the Bible and the Forgotten Books of Eden (1926) is a collection of 17th-century and 18th-century English translations of some Old Testament Pseudepigrapha and New Testament Apocrypha, some of which were assembled in the 1820s, and then republished with the current title in 1926.

The First Epistle of Clement is a letter addressed to the Christians in the city of Corinth. The work is attributed to Clement I, the fourth bishop of Rome and almost certainly written by him. Based on internal evidence some scholars say the letter was composed some time before AD 70, but the common time given for the epistle's composition is at the end of the reign of Domitian. As the name suggests, a Second Epistle of Clement is known, but this is a later work by a different author.

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations also includes deuterocanonical books. Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants use different canons, which differ with respect to the texts that are included in the Old Testament.

This is a glossary of terms used in Christianity.

A biblical canon is a set of texts which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible.

Lazar Jovanović was a Bosnian Serb manuscript writer from the first half of the 19th century. He worked as a teacher at Serb elementary schools in Tešanj and Tuzla, in the north-east of the Ottoman province of Bosnia. He wrote, illuminated and bound two books in 1841 and 1842. The first book was commissioned by Serb members of the guild of goldsmiths in Sarajevo. It contains a collection of advice to be presented to journeymen on the ceremony of their promotion to master craftsmen. His second book contains a version of the apocryphal epistle known as the Epistle of Christ from Heaven. Although Jovanović states that he writes in Slavonic-Serbian, the language of his books is basically vernacular Serbian of the Ijekavian accent. He follows traditional Church Slavonic orthography, rather than the reformed Serbian Cyrillic introduced in 1818.