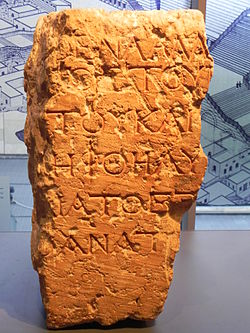

| Temple Warning Inscription | |

|---|---|

The inscription in its current location | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Writing | Greek |

| Created | c. 23 BCE – 70 CE [1] |

| Discovered | 1871 |

| Present location | Istanbul Archaeology Museums |

| Identification | 2196 T |

The Temple Warning inscription, also known as the Temple Balustrade inscription or the Soreg inscription, [2] is an inscription that hung along the balustrade outside the Sanctuary of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Two of these tablets have been found. [3] The inscription was a warning to pagan visitors to the temple not to proceed further. Both Greek and Latin inscriptions on the temple's balustrade served as warnings to pagan visitors not to proceed under penalty of death. [3] [4]

Contents

A complete tablet was discovered in 1871 by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, in the ad-Dawadariya school just outside the al-Atim Gate to the Temple Mount, and published by the Palestine Exploration Fund. [1] [5] Following the discovery of the inscription, it was taken by the Ottoman authorities, and it is currently in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums. A partial fragment of a less well made version of the inscription was found in 1936 by J. H. Iliffe during the excavation of a new road outside Jerusalem's Lions' Gate; it is held in the Israel Museum. [1] [6] [7]