William Hogarth was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects", and he is perhaps best known for his series A Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode. Knowledge of his work is so pervasive that satirical political illustrations in this style are often referred to as "Hogarthian".

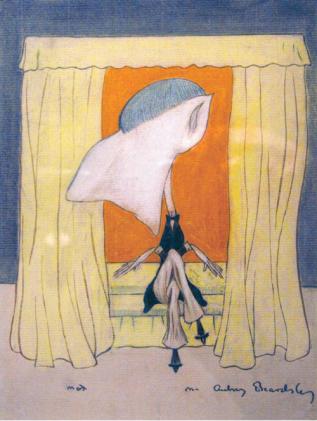

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings. Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, and can serve a political purpose, be drawn solely for entertainment, or for a combination of both. Caricatures of politicians are commonly used in newspapers and news magazines as political cartoons, while caricatures of movie stars are often found in entertainment magazines.

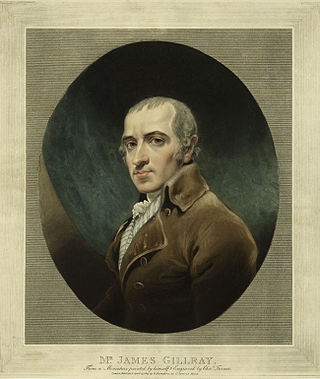

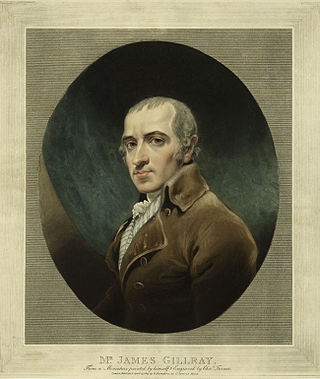

James Gillray was a British caricaturist and printmaker famous for his etched political and social satires, mainly published between 1792 and 1810. Many of his works are held at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

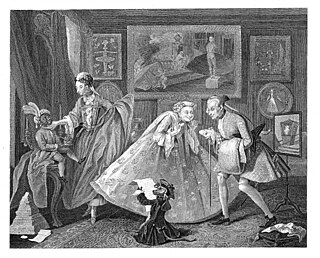

A Harlot's Progress is a series of six paintings and engravings (1732) by the English artist William Hogarth. The series shows the story of a young woman, M. Hackabout, who arrives in London from the country and becomes a prostitute. The series was developed from the third image. After painting a prostitute in her boudoir in a garret on Drury Lane, Hogarth struck upon the idea of creating scenes from her earlier and later life. The title and allegory are reminiscent of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress.

The Four Stages of Cruelty is a series of four printed engravings published by English artist William Hogarth in 1751. Each print depicts a different stage in the life of the fictional Tom Nero.

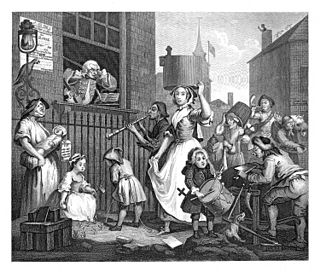

Four Times of the Day is a series of four oil paintings by English artist William Hogarth. They were completed in 1736 and in 1738 were reproduced and published as a series of four engravings. They are humorous depictions of life in the streets of London, the vagaries of fashion, and the interactions between the rich and poor. Unlike many of Hogarth's other series, such as A Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress, Industry and Idleness, and The Four Stages of Cruelty, it does not depict the story of an individual, but instead focuses on the society of the city in a humorous manner. Hogarth does not offer a judgment on whether the rich or poor are more deserving of the viewer's sympathies. In each scene, while the upper and middle classes tend to provide the focus, there are fewer moral comparisons than seen in some of his other works. Their dimensions are about 74 cm (29 in) by 61 cm (24 in) each.

The Gate of Calais or O, the Roast Beef of Old England is a 1748 painting by William Hogarth, reproduced as a print from an engraving the next year. Hogarth produced the painting directly after his return from France, where he had been arrested as a spy while sketching in Calais. The scene depicts a side of beef being transported from the harbour to an English tavern in the port, while a group of undernourished, ragged French soldiers and a fat friar look on hungrily. Hogarth painted himself in the left corner with a "soldier's hand upon my shoulder."

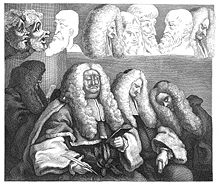

Characters and Caricaturas is an engraving by English artist William Hogarth that he produced as the subscription ticket for his 1743 series of prints, Marriage à-la-mode, and which was eventually issued as a print in its own right. Critics had sometimes dismissed the exaggerated features of Hogarth's characters as caricature and, by way of an answer, he produced this picture filled with characterisations accompanied by a simple illustration of the difference between characterisation and caricature.

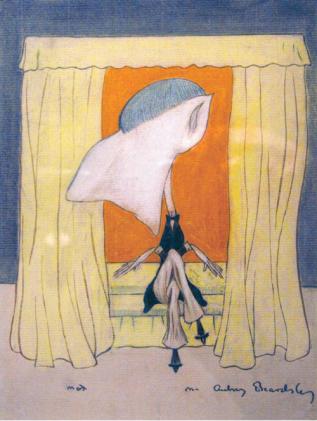

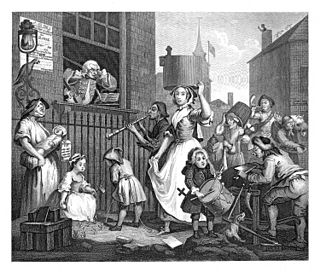

The Enraged Musician is a 1741 etching and engraving by English artist William Hogarth which depicts a comic scene of a violinist driven to distraction by the cacophony outside his window. It was issued as companion piece to the third state of his print of The Distrest Poet.

The Distrest Poet is an oil painting produced sometime around 1736 by the British artist William Hogarth. Reproduced as an etching and engraving, it was published in 1741 from a third state plate produced in 1740. The scene was probably inspired by Alexander Pope's satirical poem The Dunciad. It depicts a scene in a small, dingy attic room where a poet sits at his desk in the dormer and, scratching his head, stares at the papers on the desk before him, evidently looking for inspiration to complete the poem he is writing. Near him sits his wife darning clothes, surprised by the entrance of a milkmaid, who impatiently demands payment of debts.

Beer Street and Gin Lane are two prints issued in 1751 by English artist William Hogarth in support of what would become the Gin Act. Designed to be viewed alongside each other, they depict the evils of the consumption of gin as a contrast to the merits of drinking beer. At almost the same time and on the same subject, Hogarth's friend Henry Fielding published An Inquiry into the Late Increase in Robbers. Issued together with The Four Stages of Cruelty, the prints continued a movement started in Industry and Idleness, away from depicting the laughable foibles of fashionable society and towards a more cutting satire on the problems of poverty and crime.

Mary and Matthew Darly were English printsellers and caricaturists during the 1770s. Mary Darly was a printseller, caricaturist, artist, engraver, writer, and teacher. She wrote, illustrated, and published the first book on caricature drawing, A Book of Caricaturas [sic], aimed at "young gentlemen and ladies." Mary was the wife of Matthew Darly, also called Matthias, a London printseller, furniture designer, and engraver. Mary was evidently the second wife of Matthew; his first was named Elizabeth Harold.

Columbus Breaking the Egg is a 1752 engraving by English artist William Hogarth. Issued as the subscription ticket for his treatise on art, The Analysis of Beauty, it depicts an apocryphal tale concerning Christopher Columbus's response to detractors of his discovery of the New World. Hogarth uses the story as a parallel to what he considered his own discoveries in art.

Hogarth Painting the Comic Muse is a painting in the National Portrait Gallery, London by the British artist William Hogarth. It was painted in approximately 1757 and published as a print in etching and engraving in 1758, with its final and sixth state in 1764. Hogarth used this particular self-portrait as the frontispiece of his collected engravings, published in 1764.

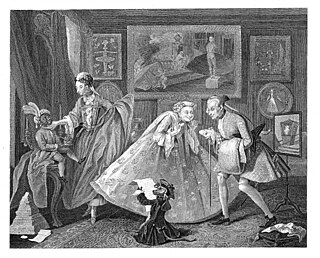

Taste in High Life is an oil-on-canvas painting from around 1742, by William Hogarth. The version seen on the right was engraved by Samuel Phillips in 1798, under commission from John Boydell for a posthumous edition of Hogarth's works, but Phillips's final, third state was not published until 1808.

The March of the Guards to Finchley, also known as The March to Finchley or The March of the Guards, is a 1750 oil-on-canvas painting by English artist William Hogarth, owned by and on display at the Foundling Museum. Hogarth was well known for his satirical works, and The March of the Guards to Finchley has been said to have given full scope to this sense of satire; it was described by Hogarth himself as "steeped in humour".

Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme is an early print by William Hogarth, created in 1721 and widely published from 1724. It caricatures the financial speculation, corruption and credulity that caused the South Sea Bubble in England in 1720–21. The print is often considered the first editorial cartoon or as a precursor of the form.

Heads of Six of Hogarth's Servants is an oil-on-canvas painting by William Hogarth from c. 1750-5. Measuring 63 centimetres (25 in) high and 75.5 centimetres (29.7 in) wide, it depicts the heads of six of his domestic servants. It is held by in Tate Britain in London.

Trump was a pug owned by English painter William Hogarth. He included the dog in several works, including his 1745 self-portrait Painter and his Pug, held by the Tate Gallery. In the words of the Tate's display caption, "Hogarth's pug dog, Trump, serves as an emblem of the artist's own pugnacious character."