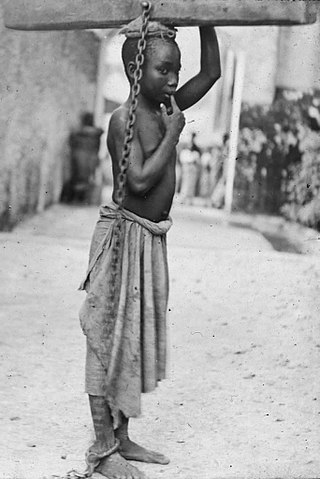

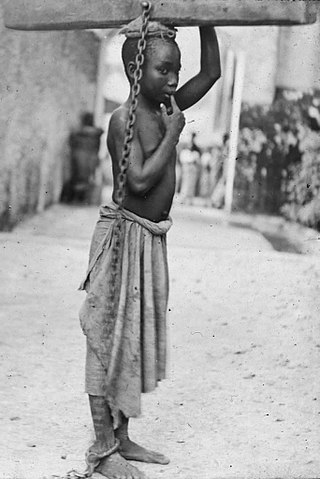

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage. Europeans established a coastal slave trade in the 15th century and trade to the Americas began in the 16th century, lasting through the 19th century. The vast majority of those who were transported in the transatlantic slave trade were from Central Africa and West Africa and had been sold by West African slave traders to European slave traders, while others had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids. European slave traders gathered and imprisoned the enslaved at forts on the African coast and then brought them to the Americas. Some Portuguese and Europeans participated in slave raids. As the National Museums Liverpool explains: "European traders captured some Africans in raids along the coast, but bought most of them from local African or African-European dealers." Many European slave traders generally did not participate in slave raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade because of malaria that was endemic in the African continent. An article from PBS explains: "Malaria, dysentery, yellow fever, and other diseases reduced the few Europeans living and trading along the West African coast to a chronic state of ill health and earned Africa the name 'white man's grave.' In this environment, European merchants were rarely in a position to call the shots." The earliest known use of the phrase began in the 1830s, and the earliest written evidence was found in an 1836 published book by F. H. Rankin. Portuguese coastal raiders found that slave raiding was too costly and often ineffective and opted for established commercial relations.

The globalAfrican diaspora is the worldwide collection of communities descended from people from Africa, predominantly in the Americas. The African populations in the Americas are descended from haplogroup L genetic groups of native Africans. The term most commonly refers to the descendants of the native West and Central Africans who were enslaved and shipped to the Americas via the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries, with their largest populations in Brazil, the United States, Colombia and Haiti. However, the term can also be used to refer to African descendants who immigrated to other parts of the world. Scholars identify "four circulatory phases" of this migration out of Africa. The phrase African diaspora gradually entered common usage at the turn of the 21st century. The term diaspora originates from the Greek διασπορά which gained popularity in English in reference to the Jewish diaspora before being more broadly applied to other populations.

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who were primarily of black African descent with little mixture. They were a distinct group of free people of color in the French colonies, including Louisiana and in settlements on Caribbean islands, such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti), St. Lucia, Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. In these territories and major cities, particularly New Orleans, and those cities held by the Spanish, a substantial third class of primarily mixed-race, free people developed. These colonial societies classified mixed-race people in a variety of ways, generally related to visible features and to the proportion of African ancestry. Racial classifications were numerous in Latin America.

The Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known slave uprising in human history that led to the founding of a state which was both free from slavery and ruled by non-whites and former captives.

Afro-Caribbean or African Caribbeanpeople are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Africa. The majority of the modern Afro-Caribbean people descend from the Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 15th and 19th centuries to work primarily on various sugar plantations and in domestic households. Other names for the ethnic group include Black Caribbean, Afro- or Black West Indian, or Afro- or Black Antillean. The term West Indian Creole has also been used to refer to Afro-Caribbean people, as well as other ethnic and racial groups in the region, though there remains debate about its use to refer to Afro-Caribbean people specifically. The term Afro-Caribbean was not coined by Caribbean people themselves but was first used by European Americans in the late 1960s.

Afro-Caribbean music is a broad term for music styles originating in the Caribbean from the African diaspora. These types of music usually have West African/Central African influence because of the presence and history of African people and their descendants living in the Caribbean, as a result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. These distinctive musical art forms came about from the cultural mingling of African, Indigenous, and European inhabitants. Characteristically, Afro-Caribbean music incorporates components, instruments and influences from a variety of African cultures, as well as Indigenous and European cultures.

Sidney Wilfred Mintz was an American anthropologist best known for his studies of the Caribbean, creolization, and the anthropology of food. Mintz received his PhD at Columbia University in 1951 and conducted his primary fieldwork among sugar-cane workers in Puerto Rico. Later expanding his ethnographic research to Haiti and Jamaica, he produced historical and ethnographic studies of slavery and global capitalism, cultural hybridity, Caribbean peasants, and the political economy of food commodities. He taught for two decades at Yale University before helping to found the Anthropology Department at Johns Hopkins University, where he remained for the duration of his career. Mintz's history of sugar, Sweetness and Power, is considered one of the most influential publications in cultural anthropology and food studies.

The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution is a 1938 book by Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James, a history of the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804.

Richard Price is an American anthropologist and historian, best known for his studies of the Caribbean and his experiments with writing ethnography.

The Haitian Declaration of Independence was proclaimed on 1 January 1804 in the port city of Gonaïves by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, marking the end of 13-year long Haitian Revolution. The declaration marked Haiti becoming the first independent nation of Latin America and only the second in the Americas after the United States.

For a history of Afro-Caribbean people in the UK, see British African Caribbean community.

Afro-Haitians or Black Haitians are Haitians who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. They form the largest racial group in Haiti and together with other Afro-Caribbean groups, the largest racial group in the region.

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic slave trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practiced on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

The Wesley Logan Prize is an annual prize given to a historian by the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life & History

Laurent Dubois is the John L. Nau III Bicentennial Professor in the History & Principles of Democracy. A specialist on the history and culture of the Atlantic world who studies the Caribbean, North America, and France, Dubois joined the University of Virginia in January 2021, and will also serve as the Democracy Initiative’s Director for Academic Affairs. In this role, Dubois will spearhead the Democracy Initiative’s research and pedagogical missions and will serve as the director and lead research convener of the John L. Nau III History and Principles of Democracy Lab—the permanent core lab of the Initiative which will operate as the connecting hub for the entire project. His studies have focused on Haiti.

Capitalism and Slavery is the published version of the doctoral dissertation of Eric Williams, who was the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago in 1962. It advances a number of theses on the impact of economic factors on the decline of slavery, specifically the Atlantic slave trade and slavery in the British West Indies, from the second half of the 18th century. It also makes criticisms of the historiography of the British Empire of the period: in particular on the use of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 as a sort of moral pivot; but also directed against a historical school that saw the imperial constitutional history as a constant advance through legislation. It uses polemical asides for some personal attacks, notably on the Oxford historian Reginald Coupland. Seymour Drescher, a prominent critic among historians of some of the theses put forward in Capitalism and Slavery by Williams, wrote in 1987: "If one criterion of a classic is its ability to reorient our most basic way of viewing an object or a concept, Eric Williams's study supremely passes that test."

Julius Sherrod Scott III was an American scholar of slavery and Caribbean and Atlantic history. He was best known for his influential doctoral thesis and later book The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. Scott's original thesis has been regarded as "arguably the most read, sought after and discussed English-language dissertation in the humanities and social sciences during the 20th century", elevating the historian to the position of an intellectual "cult figure among scholars" in the field.

Alex Dupuy is a retired sociology professor emeritus and author in the United States. He chaired Wesleyan University’s African American Studies department and was its John E. Andrus Professor of Sociology. Born in Haiti, he has written books and essays on Haiti. An oral interview with him was recorded by Wesleyan in March 2019.