William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. What he called his "prophetic works" were said by 20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language". While he lived in London his entire life, except for three years spent in Felpham, he produced a diverse and symbolically rich collection of works, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God", or "human existence itself".

Thomas Stothard was a British painter, illustrator and engraver. His son, Robert T. Stothard was a painter : he painted the proclamation outside York Minster of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne in June 1837.

Rev Robert Blair was a Scottish poet. His fame rests upon his poem The Grave, which in a later printing was illustrated by William Blake.

Ruthven Campbell Todd was a Scottish poet, artist and novelist, best known as an editor of the works of William Blake, and expert on his printing techniques. During the 1940s he also wrote detective fiction under the pseudonym R. T. Campbell and children's fiction during the 1950s.

"The Tyger" is a poem by the English poet William Blake, published in 1794 as part of his Songs of Experience collection and rising to prominence in the romantic period. The poem is one of the most anthologised in the English literary canon, and has been the subject of both literary criticism and many adaptations, including various musical versions. The poem explores and questions Christian religious paradigms prevalent in late 18th century and early 19th century England, discussing God's intention and motivation for creating both the tiger and the Lamb.

Earth's Answer is a poem by William Blake within his larger collection called Songs of Innocence and of Experience. It is the response to the previous poem in The Songs of Experience-- Introduction . In the Introduction, the bard asks the Earth to wake up and claim ownership. In this poem, the feminine Earth responds.

"Infant Joy" is a poem written by the English poet William Blake. It was first published as part of his collection Songs of Innocence in 1789 and is the counterpart to "Infant Sorrow", which was published at a later date in Songs of Experience in 1794.

Robert Hartley Cromek (1770–1812) was an English engraver, editor, art dealer and entrepreneur who was most active in the early nineteenth century. He is best known for having allegedly cheated William Blake out of the potential profits of his engraving depicting Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims.

The Song of Los is one of William Blake's epic poems, known as prophetic books. The poem consists of two sections, "Africa" and "Asia". In the first section Blake catalogues the decline of morality in Europe, which he blames on both the African slave trade and enlightenment philosophers. The book provides a historical context for The Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los, and also ties those more obscure works to The Continental Prophecies, "Europe" and "America". The second section consists of Los urging revolution.

Nebuchadnezzar is a colour monotype print with additions in ink and watercolour portraying the Old Testament Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II by the English poet, painter, and printmaker William Blake. Taken from the Book of Daniel, the legend of Nebuchadnezzar tells of a ruler who through hubris lost his mind and was reduced to animalistic madness and eating "grass as oxen".

The Ghost of a Flea is a miniature painting by the English poet, painter and printmaker William Blake, held in the Tate Gallery, London. Measuring only 8.42 by 6.3 inches, it is executed in a tempera mixture with gold, on a mahogany-type tropical hardwood panel. It was completed between 1819 and 1820, as part of a series depicting "Visionary Heads" commissioned by the watercolourist and astrologist John Varley (1778–1842). Fantastic, spiritual art was popular in Britain from around 1770 to 1830, and during this time Blake often worked on unearthly, supernatural panels to amuse and amaze his friends.

The French Revolution is a poem written by William Blake in 1791. It was intended to be seven books in length, but only one book survives. In that book, Blake describes the problems of the French monarchy and seeks the destruction of the Bastille in the name of Freedom.

A Vision of the Last Judgement is a painting by William Blake that was designed in 1808 before becoming a lost artwork. The painting was to be shown in an 1810 exhibition with a detailed analysis added to a second edition of his Descriptive Catalogue. This plan was dropped after the exhibition was cancelled, and the painting disappeared. Blake's notes for the Descriptive Catalogue describe various aspects of the work in a detailed manner, which allow the aspects of the painting to be known. Additionally, earlier designs that reveal similar Blake depiction of the Last Judgement have survived, and these date back to an 1805 precursor design created for Robert Blair's The Grave. In addition to Blake's notes on the painting, a letter written to Ozias Humphrey provides a description of the various images within an earlier design of the Last Judgement.

The Life of William Blake, "Pictor Ignotus." With selections from his poems and other writings is a two-volume work on the English painter and poet William Blake, first published in 1863. The first volume is a biography and the second a compilation of Blake's poetry, prose, artwork and illustrated manuscript.

Pity is a colour print on paper, finished in ink and watercolour, by the English artist and poet William Blake, one of the group known as the "Large Colour Prints". Along with his other works of this period, it was influenced by the Bible, Milton, and Shakespeare. The work is unusual, as it is a literal illustration of a double simile from Macbeth, found in the lines:

Robert Hunt was an English writer. His infamous reviews of the works of William Blake are amongst the earliest criticism of the poet and painter.

Maria Flaxman was a British painter and illustrator.

The Notebook of William Blake was used by William Blake as a commonplace book from c. 1787 to 1818.

"The Human Abstract" is a poem written by the English poet William Blake. It was published as part of his collection Songs of Experience in 1794. The poem was originally drafted in Blake's notebook and was later revised for as part of publication in Songs of Experience. Critics of the poem have noted it as demonstrative of Blake's metaphysical poetry and its emphasis on the tension between the human and the divine.

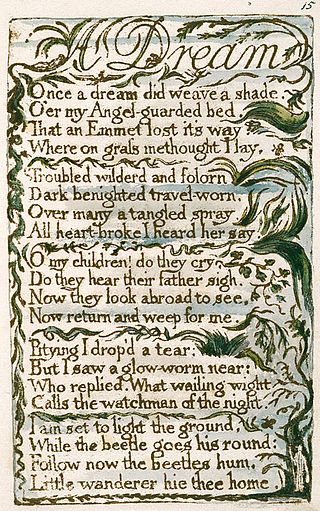

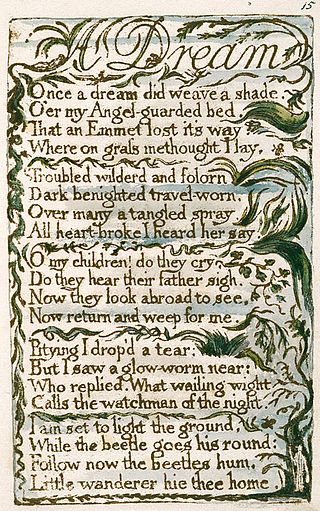

"A Dream" is a poem by English poet William Blake. The poem was first published in 1789 as part of Blake's collection of poems entitled Songs of Innocence.