A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919) and is derived from the word toxic.

Poison is something that causes harm. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broad sense.

Ricinus communis, the castor bean or castor oil plant, is a species of perennial flowering plant in the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae. It is the sole species in the monotypic genus, Ricinus, and subtribe, Ricininae. The evolution of castor and its relation to other species are currently being studied using modern genetic tools. It reproduces with a mixed pollination system which favors selfing by geitonogamy but at the same time can be an out-crosser by anemophily or entomophily.

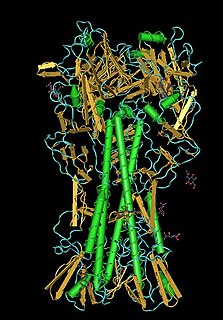

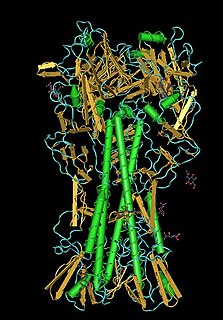

Ricin ( RY-sin) is a lectin (a carbohydrate-binding protein) and a highly potent toxin produced in the seeds of the castor oil plant, Ricinus communis. The median lethal dose (LD50) of ricin for mice is around 22 micrograms per kilogram of body weight via intraperitoneal injection. Oral exposure to ricin is far less toxic. An estimated lethal oral dose in humans is approximately 1 milligram per kilogram of body weight.

Abrus precatorius, commonly known as jequirity bean or rosary pea, is a herbaceous flowering plant in the bean family Fabaceae. It is a slender, perennial climber with long, pinnate-leafleted leaves that twines around trees, shrubs, and hedges.

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins that are highly specific for sugar groups that are part of other molecules, so cause agglutination of particular cells or precipitation of glycoconjugates and polysaccharides. Lectins have a role in recognition at the cellular and molecular level and play numerous roles in biological recognition phenomena involving cells, carbohydrates, and proteins. Lectins also mediate attachment and binding of bacteria, viruses, and fungi to their intended targets.

Adenia is a genus of flowering plants in the passionflower family, Passifloraceae. It is distributed in the Old World tropics and subtropics. The centers of diversity are in Madagascar, eastern and western tropical Africa, and Southeast Asia. The genus name Adenia comes from "aden", reported as the Arabic name for the plant by Peter Forsskål, the author of the genus.

Cicutoxin is a naturally-occurring poisonous chemical compound produced by several plants from the family Apiaceae including water hemlock (Cicuta species) and water dropwort (Oenanthe crocata). The compound contains polyene, polyyne, and alcohol functional groups and is a structural isomer of oenanthotoxin, also found in water dropwort. Both of these belong to the C17-polyacetylenes chemical class.

Abrin is an extremely toxic toxalbumin found in the seeds of the rosary pea, Abrus precatorius. It has a median lethal dose of 0.7 micrograms per kilogram of body mass when given to mice intravenously. The median toxic dose for humans ranges from 10 to 1000 micrograms per kilogram when ingested and is 3.3 micrograms per kilogram when inhaled.

Amatoxin is the collective name of a subgroup of at least nine related toxic compounds found in three genera of poisonous mushrooms and one species of the genus Conocybe. Amatoxins are lethal in even small doses, as little as half a mushroom, including the immature 'egg' form which appears quite different from the fully-grown mushroom.

The trichothecenes are a large family of chemically related mycotoxins. They are produced by various species of Fusarium, Myrothecium, Trichoderma/Podostroma, Trichothecium, Cephalosporium, Verticimonosporium, and Stachybotrys. Chemically, trichothecenes are a class of sesquiterpenes.

Phytotoxins are substances that are poisonous or toxic to the growth of plants. Phytotoxic substances may result from human activity, as with herbicides, or they may be produced by plants, by microorganisms, or by naturally occurring chemical reactions.

Saporin is a protein that is useful in biological research applications, especially studies of behavior. Saporin is a so-called ribosome inactivating protein (RIP), due to its N-glycosidase activity, from the seeds of Saponaria officinalis. It was first described by Fiorenzo Stirpe and his colleagues in 1983 in an article that illustrated the unusual stability of the protein.

Peter Hermann Stillmark was a Baltic-German microbiologist.

A ribosome-inactivating protein (RIP) is a protein synthesis inhibitor that acts at the eukaryotic ribosome. This protein family describes a large family of such proteins that work by acting as rRNA N-glycosylase. They inactivate 60S ribosomal subunits by an N-glycosidic cleavage, which releases a specific adenine base from the sugar-phosphate backbone of 28S rRNA. RIPs exist in bacteria and plants.

Ricinine is a toxic alkaloid found in the castor plant. It can serve as a biomarker of ricin poisoning. It was first isolated from the castor seeds by Tuson in 1864.

Volkensin is a eukaryotic ribosome-inactivating protein found in the Adenia volkensii plant. It is a glycoprotein with two subunits A and B. A subunit is linked to B subunit with disulfide bridges and non-covalent bonds. B subunit is responsible for binding to the galactosyl-terminated receptors on the cell membrane that allows the entry the A subunit of the toxin into the cell, which performs the inhibitory function. Volkensin is a galactose specific lectin that can inhibit protein synthesis in whole cells and in cell-free lysates. This protein can be included into the category of risin like toxins and it resembles modeccin, the toxin of Adenia digitata. Although very similar in composition, volkensin contains more cysteine residues and more than twice as much sugar than modeccin, due to high content of galactose and mannose. In addition, volkensin is able to inhibit protein synthesis at concentrations 10 times lower than required for modeccin. From gene sequencing analysis, volkensin was found to be coded by 1569-bp ORF, that is 523 amino acid residues without introns. The internal linker sequence is 45 bp. The active site of the A subunit contains Ser203, a novel residue that is conserved in all ribosome inactivating proteins.

Modeccin is a toxic lectin, a group of glycoproteins capable of binding specifically to sugar moieties. Different toxic lectins are present in seeds of different origin. Modeccin is found in the roots of the African plant Adenia digitata. These roots are often mistaken for edible roots, which has led to some cases of intoxication. Sometimes the fruit is eaten, or a root extract is drunk as a manner of suicide.

There are a wide variety of substances poisonous to dogs. Many pet owners have a general knowledge of dog health, but not of the larger scope of common substances poisonous to dogs. Recognizing the signs of poisoning will enable dog owners to get the help their dogs need when exposed to poisons. Dogs can be exposed to poisons in several ways: ingestion, contact, and inhalation. The most common poisonous substances include some human foods and medications, household products, and many plants. Understanding exposure and symptoms of poisoning and poisonous substances will assist dog owners in identifying how to get the correct treatment for their pet.