Related Research Articles

The Indian removal was the United States government's policy of ethnic cleansing through the forced displacement of self-governing tribes of American Indians from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River—specifically, to a designated Indian Territory, which many scholars have labeled a genocide. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, the key law which authorized the removal of Native tribes, was signed into law by United States president Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830. Although Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, the law was primarily enforced during the Martin Van Buren administration. After the enactment of the Act, approximately 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands, with thousands dying during the Trail of Tears.

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek or just Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy, are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands in the United States. Their historical homelands are in what now comprises southern Tennessee, much of Alabama, western Georgia and parts of northern Florida.

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent nation-state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty which was carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act. The treaty ceded about 11 million acres (45,000 km2) of the Choctaw Nation in what is now Mississippi in exchange for about 15 million acres (61,000 km2) in the Indian territory, now the state of Oklahoma. The principal Choctaw negotiators were Chief Greenwood LeFlore, Mosholatubbee, and Nittucachee; the U.S. negotiators were Colonel John Coffee and Secretary of War John Eaton.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes in October 1867, intended to bring peace to the area by relocating the Native Americans to reservations in Indian Territory and away from European-American settlement. The treaty was negotiated after investigation by the Indian Peace Commission, which in its final report in 1868 concluded that the wars had been preventable. They determined that the United States government and its representatives, including the United States Congress, had contributed to the warfare on the Great Plains by failing to fulfill their legal obligations and to treat the Native Americans with honesty.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie is an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of the first Fort Laramie treaty, signed in 1851.

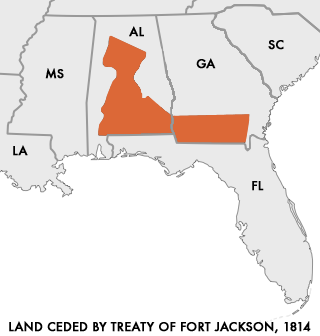

The Treaty of Fort Jackson was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick resistance by United States allied forces at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

Three agreements, each known as a Treaty of Hopewell, were signed between representatives of the Congress of the United States and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw peoples. They were negotiated and signed at the Hopewell plantation in South Carolina over 45 days during the winter of 1785–86.

Kicking Bird, also known as Tene-angop'te, "The Kicking Bird", "Eagle Who Strikes with his Talons", or "Striking Eagle" was a High Chief of the Kiowa in the 1870s. It is said that he was given his name for the way he fought his enemies. He was a Kiowa, though his grandfather had been a Crow captive who was adopted by the Kiowa. His mysterious death at Fort Sill on May 3, 1875, is the subject of much debate and speculation.

This Fort Bridger Treaty Council of 1868, was also known as the Great Treaty Council, was a council that developed the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. The Shoshone, also referred to as the Shoshoni or Snake, were the main American Indian group affected by this treaty. The event itself is significant because it was the last treaty council which dealt with establishing a reservation. After that council, executive Orders were used to establish reservations.

The Tawakoni are a Southern Plains Native American tribe, closely related to the Wichitas. They historically spoke a Wichita language of the Caddoan language family. Currently, they are enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, a federally recognized tribe.

The Council House Fight, often referred to as the Council House Massacre, was a fight between soldiers and officials of the Republic of Texas and a delegation of Comanche chiefs during a peace conference in San Antonio on March 19, 1840. About 35 Comanche men and women under chief, Mukwooru represented just a fraction of the Penateka band of the southern portion of the Comanche tribe. He knew he had no authority to speak for the Southern tribes as a whole and thus, any discussions of peace would be simply a farce. However, if Mukwooru could re-establish a lucrative trade with the San Antonian's perhaps a peace, by proxy, could be established. Just as the Comanche had done had been done for centuries in San Antonio, Santa Fe and along the Rio Grande River. They would rob one settlement and then sell to the other.

The Texas–Indian wars were a series of conflicts between settlers in Texas and the Southern Plains Indians during the 19th-century. Conflict between the Plains Indians and the Spanish began before other European and Anglo-American settlers were encouraged—first by Spain and then by the newly Independent Mexican government—to colonize Texas in order to provide a protective-settlement buffer in Texas between the Plains Indians and the rest of Mexico. As a consequence, conflict between Anglo-American settlers and Plains Indians occurred during the Texas colonial period as part of Mexico. The conflicts continued after Texas secured its independence from Mexico in 1836 and did not end until 30 years after Texas became a state of the United States, when in 1875 the last free band of Plains Indians, the Comanches led by Quahadi warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

Chitto Harjo was a leader and orator among the traditionalists in the Muscogee Creek Nation in Indian Territory at the turn of the 20th century. He resisted changes which the US government and local leaders wanted to impose to achieve statehood for what became Oklahoma. These included extinguishing tribal governments and civic institutions and breaking up communal lands into allotments to individual households, with United States sales of the "surplus" to European-American and other settlers. He was the leader of the Crazy Snake Rebellion on March 25, 1909 in Oklahoma. At the time this was called the last "Indian uprising".

The Treaty of Bird's Fort, or Bird's Fort Treaty was a peace treaty between the Republic of Texas and some of the Indian tribes of Texas and Oklahoma, signed on September 29, 1843. The treaty was intended to end years of hostilities and warfare between the Native Americans and the white settlers in Texas. The full title of the treaty was "Republic of Texas Treaty with the Indigenous Nations of the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tawakani, Keechi, Caddo, Anadahkah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee." The principal negotiators for the Republic of Texas were Edward H. Tarrant and George W. Terrell.

The Cherokee have participated in over forty treaties in the past three hundred years.

The Fort Martin Scott Treaty of 1850 was an unratified treaty between the United States government and the Comanche, Caddo, Quapaw, Tawakoni, Lipan Apache, and Waco tribes in Texas. The treaty was signed in San Saba County, Texas, but named after the nearest military outpost, Fort Martin Scott in Gillespie County, on the outskirts of Fredericksburg.

The Treaty of Bosque Redondo also the Navajo Treaty of 1868 or Treaty of Fort Sumner, Navajo Naal Tsoos Sani or Naaltsoos Sání) was an agreement between the Navajo and the US Federal Government signed on June 1, 1868. It ended the Navajo Wars and allowed for the return of those held in internment camps at Fort Sumner following the Long Walk of 1864. The treaty effectively established the Navajo as a sovereign nation.

Yellow Wolf, Spirit Talker 's nephew and Buffalo Hump 's cousin and best support, was a War Chief of the Penateka division of the Comanche Indians. He came to prominence after the Council House Fight, when Buffalo Hump called the Comanches and, along with Yellow Wolf and Santa Anna, led them in the Great Raid of 1840.

Sam Houston had a diverse relationship with Native Americans, particularly the Cherokee from Tennessee. He was an adopted son, and he was a negotiator, strategist, and creator of fair public policy for Native Americans as a legislator, governor and president of the Republic of Texas. He left his widowed mother's home around 1808 and was taken in by John Jolly, a leader of the Cherokee. Houston lived in Jolly's village for three years. He adopted Cherokee customs and traditions, which stressed the importance of being honest and fair, and he learned to speak the Cherokee language. He felt that Cherokees and other indigenous people had been short-changed during negotiation of treaties with United States government, the realization influenced his decisions as a military officer, treaty negotiator, and in his roles as governor of the states of Tennessee and Texas, and president of the Republic of Texas.

References

- ↑ "Tehuacana Creek Treaty". Indians.org. Retrieved 2011-05-22.