Coccidioidomycosis, is a mammalian fungal disease caused by Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii. It is commonly known as cocci, Valley fever, as well as California fever, desert rheumatism, or San Joaquin Valley fever. Coccidioidomycosis is endemic in certain parts of the United States in Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, and northern Mexico.

Coccidioides immitis is a pathogenic fungus that resides in the soil in certain parts of the southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and a few other areas in the Western Hemisphere.

Coccidioides is a genus of dimorphic ascomycetes in the family Onygenaceae. Member species are the cause of coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever, an infectious fungal disease largely confined to the Western Hemisphere and endemic in the Southwestern United States. The host acquires the disease by respiratory inhalation of spores disseminated in their natural habitat. The causative agents of coccidioidomycosis are Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Both C. immitis and C. posadasii are indistinguishable during laboratory testing and commonly referred in literature as Coccidioides.

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus that causes blastomycosis, an invasive and often serious fungal infection found occasionally in humans and other animals. It lives in soil and wet, decaying wood, often in an area close to a waterway such as a lake, river or stream. Indoor growth may also occur, for example, in accumulated debris in damp sheds or shacks. The fungus is endemic to parts of eastern North America, particularly boreal northern Ontario, southeastern Manitoba, Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, parts of the U.S. Appalachian mountains and interconnected eastern mountain chains, the west bank of Lake Michigan, the state of Wisconsin, and the entire Mississippi Valley including the valleys of some major tributaries such as the Ohio River. In addition, it occurs rarely in Africa both north and south of the Sahara Desert, as well as in the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent. Though it has never been directly observed growing in nature, it is thought to grow there as a cottony white mold, similar to the growth seen in artificial culture at 25 °C (77 °F). In an infected human or animal, however, it converts in growth form and becomes a large-celled budding yeast. Blastomycosis is generally readily treatable with systemic antifungal drugs once it is correctly diagnosed; however, delayed diagnosis is very common except in highly endemic areas.

Coccidioides posadasii is a pathogenic fungus that, along with Coccidioides immitis, is the causative agent of coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever in humans. It resides in the soil in certain parts of the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and some other areas in the Americas, but its evolution was connected to its animal hosts.

Chlamydosauromyces punctatus is the sole species in the monotypic genus of fungi, Chlamydosauromyces in the family, Onygenaceae. It was found in the skin shed from frilled lizard. This fungus is mesophilic and digests hair. It reproduces both sexually and asexually. The fungus has so far not been reported to be pathogenic.

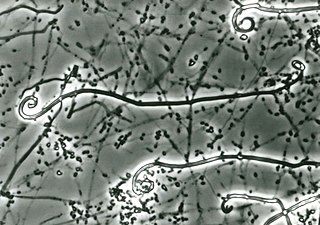

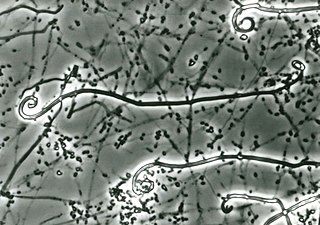

Uncinocarpus is a genus of fungi within the Onygenaceae family. The name is derived from the Latin word uncinus, meaning "hook" and the Greek word karpos (καρπός), meaning "fruit". It was distinguished from the genus Gymnoascus based on keratinolytic capacity, ascospore morphology and the development of hooked, occasionally spiraling appendages. Alternatively, Uncinocarpus species may possess helically coiled or smooth, wavy appendages, or lack appendages altogether, an example of such species being U. orissi.

Nannizziopsis vreisii is a keratinophilic microfungus in the Family Onygenaceae of the order Onygenales. Also included in this family are dematophytes and saprophytic species. While the ecology of N. vriessi is not well known, there has been several studies which identifies the Chrysosporium anamorph of N. vriesii as a causal agent of skin lesions in reptiles across several regions. This species is usually identified under a microscope by its white ascomata, and hyaline and globose ascospores. Like many other fungi, N. vreisii has a sexual and asexual state, the asexual states are classified as the genus Chryososporium, Malbranchea or Sporendonema.

Onychocola canadensis is a relative of the dermatophyte and an occasionally causes onychomycosis. It was described in 1990 from 3 clinical reports in Canada.

Chrysosporium keratinophilum is a mold that is closely related to the dermatophytic fungi and is mainly found in soil and the coats of wild animals to break down keratin. Chrysosporium keratinophilum is one of the more commonly occurring species of the genus Chrysosporium in nature. It is easily detected due to its characteristic "light-bulb" shape and flat base. Chrysosporium keratinophilum is most commonly found in keratin-rich, dead materials such as feathers, skin scales, hair, and hooves. Although not identified as pathogenic, it is a regular contaminant of cutaneous specimens which leads to the common misinterpretation that this fungus is pathogenic.

Amauroascus kuehnii is a fungus in the phylum Ascomycota, class Eurotiomycetes. It is keratinophilic but not known to cause any human disease. It has been isolated from animal dungs, soil, and keratinous surfaces of live or deceased animals.

Keratinophyton durum is a keratinophilic fungus, that grows on keratin found in decomposing or shed animal hair and bird feathers. Various studies conducted in Canada, Japan, India, Spain, Poland, Ivory Coast and Iraq have isolated this fungus from decomposing animal hair and bird feathers using SDA and hair-bait technique. Presence of fungus in soil sediments and their ability to decompose hairs make them a potential human pathogen.

Ctenomyces serratus is a keratinophilic fungal soil saprotroph classified by the German mycologist, Michael Emil Eduard Eidam in 1880, who found it growing on an old decayed feather. Many accounts have shown that it has a global distribution, having been isolated in select soils as well as on feathers and other substrates with high keratin content. It has also been found in indoor dust of hospitals and houses in Kanpur, Northern India and as a common keratinophilic soil fungus in urban Berlin. This species has been associated with nail infections in humans as well as skin lesions and slower hair growth in guinea pigs.

Arthrographis kalrae is an ascomycetous fungus responsible for human nail infections described in 1938 by Cochet as A. langeronii. A. kalrae is considered a weak pathogen of animals including human restricted to the outermost keratinized layers of tissue. Infections caused by this species are normally responsive to commonly used antifungal drugs with only very rare exceptions.

Myxotrichum chartarum is a psychrophilic and cellulolytic fungus first discovered in Germany by Gustav Kunze in 1823. Its classification has changed many times over its history to better reflect the information available at the time. Currently, M. chartarum is known to be an ascomycete surrounded by a gymnothecium composed of ornate spines and releases asexual ascospores. The presence of cellulolytic processes are common in fungi within the family Myxotrichaceae. M. chartarum is one of many Myxotrichum species known to degrade paper and paper products. Evidence of M. chartarum "red spot" mold formation, especially on old books, can be found globally. As a result, this fungal species and other cellulolytic molds are endangering old works of art and books. Currently, there is no evidence that suggests that species within the family Myxotrichaceae are pathogenic.

Uncinocarpus uncinatus is a species of microfungi that grows on dung and other keratinous materials such as bone. It was the second species to be designated as part of the genus Uncinocarpus. The species was first described by Randolph S. Currah in 1985; synonyms include Myxotrichum uncinatum and Gymnoascus uncinatus.

Uncinocarpus orissi is a species of microfungus that grows on dung and other keratinous materials, such as hair. It was the third species to be designated as part of the genus Uncinocarpus by Canadian mycologists Lynne Sigler, Arlene Flis and J.W. Carmichael in 1998 as a synonym for Pseudoarachniotus orissi and Aphanoascus orissi.

Uncinocarpus queenslandicus is a species of microfungi that grows in soil and keratinous materials, such as hair. It was the fourth species to be designated as part of the genus Uncinocarpus. Its name is derived from the Australian state of Queensland, where it was first isolated.

Apinisia keratinophila, formerly Myriodontium keratinophilum, is a fungus widespread in nature, most abundantly found in keratin-rich environments such as feathers, nails and hair. Despite its ability to colonize keratinous surfaces of human body, the species has been known to be non-pathogenic in man and is phylogentically distant to other human pathogenic species, such as anthropophilic dermatophytes. However, its occasional isolation from clinical specimens along with its keratinolytic properties suggest the possibility it may contribute to disease.

Auxarthron californiense is a fungus within the family Onygenaceae family and one of the type species of the genus Auxarthron. A. californiense is generally distributed around the world and it is frequently found on dung and in soil near the entrances of animal burrows.