|

| Topics |

|---|

| Notable people |

Founders

Other members |

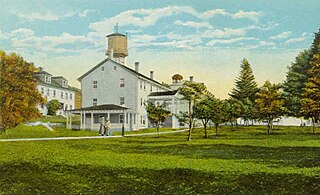

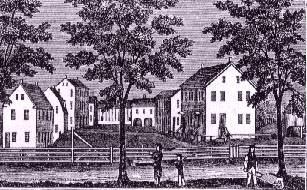

The Union Village Shaker settlement was a village organized by Shakers in Turtlecreek Township, Warren County, Ohio.

|

| Topics |

|---|

| Notable people |

Founders

Other members |

The Union Village Shaker settlement was a village organized by Shakers in Turtlecreek Township, Warren County, Ohio.

The Union Village Shaker settlement was a community of Shakers founded at Turtle Creek, Ohio, in 1805. Early leaders sent out from the Shakers' central Ministry at New Lebanon, New York, included Elder David Darrow (1750-1825), who began evangelizing in 1805, and Eldress Ruth Farrington (1763-1821), who arrived in 1806 to help stabilize the new Shaker society. An early and influential proselyte was Richard McNemar (1770-1839), who was a central figure among western Shakers for many years. [1]

The believers at Turtlecreek signed their first covenant in March 1810. The signers, separated according to sex, included these brethren: David Darrow, Daniel Mosely, Solomon King, Peter Pease, Archibald Meacham, Benjamin Seth Youngs, Issachar Bates, Elisha Dennis, Barachah Dennis, Ross Morrell, James Hodges, Nathan Sharp, Henry Morrell, John Carson, and Joseph Lockwood.

The sisters who signed the covenant were Ruth Farrington, Molly Goodrich, Ruth Darrow, Lucy Bacon, Rachel Johnson, Hortency Goodrich, Martha Sanford, Edith Dennis, Eunice Bedle, Caty Rubert, Susanna Liddil, Polly Thomas, Jenny McNemar, Polly Davis, Hannah Carson, Rachel Duncan, Rachel Dennis, and Phebe Lockwood. [2]

Until 1910, Union Village was the bishopric, or governing unit, for other Shaker villages in Ohio, including the Whitewater Shaker Settlement and the Watervliet Shaker village. After 1862, the Shaker settlement at North Union also came under Union Village's administration. After 1889, the Union Village bishopric ministry oversaw all societies in Kentucky and Ohio. [3] [4]

Shakers were led by gender-balanced teams of elders and eldresses. These individuals were suggested by local consensus and their selection was approved by the Shakers' central Ministry in New Lebanon, New York. Every bishopric's ministry was supposed to oversee the Shaker societies under their jurisdiction and keep an eye on the leaders of all the families, but this system did not always work as intended (see Joseph Slingerland, below).

From 1812 to 1821, David Darrow and his assistant Solomon King were the Ohio bishopric elders, serving with Ruth Farrington and Racel Johnson, [5]

In 1830, the Ohio bishopric ministry included Solomon King and his assistant Joshua Worley on the brethren's side, and Rachel Johnson and Nancy McNemar on the sisters' side. [6]

In 1836 and 1837, Freegift Wells, Betsey Hastings, and Sally Sharp were in the bishopric ministry. [7]

In 1840, Freegift Wells and Betsy Hastings were the lead elder and eldress; their assistants were John Martin and Sally Sharp. [8]

In 1852, the Ohio ministry were John Martin, William Reynolds, Sally Sharp, and Naomi Legier. [9]

In 1860, Aaron Babbit and Sally Sharp led the Ohio bishopric ministry, assisted by Peter Boyd, and Naomi Ligier [10]

In 1864, the Ohio bishopric ministry team consisted of Aaron Babbitt, Cephas Holloway, Sally Sharp, and Naomi Legier. [11]

In 1875, the Ohio ministry were William Reynolds, Amos Parkhurst, Naomi Legier, and Adaline Wells. [12]

In 1881, Ohio bishopric ministry included Matthew Carter, Oliver Hampton, Louisa Farnham, and Adaline Wells. [13] They were still in office in 1887. [14]

In 1818, Union Village was one of the largest Shaker settlements, with a population over 600, but by the 1830s there was a significant reduction in adult membership, [15] which was exacerbated in 1838 and 1839 due to strife among the members over ideological differences and accusations during the early years of Mother Ann's Work, also called the Era of Manifestations. [16]

As their membership dropped, Elder Oliver C. Hampton (1817-1901) began publishing spiritual works and poetry about the Shaker sect to attract people to the sect. Even so, by the 1870s the community did not have enough adult members to do the work required to support the village's farms and industries which included broom making, garden seeds, medicinal herbs and extracts. [17]

In the 1880s, contrary to the Shaker Millennial Laws, they were increasingly in debt. About 1882 James Fennessey joined the community and soon implemented a plan to rent out land to farmers to create a revenue stream. In 1892 the North Union site was sold for $316,000 which was intended to pay off the debts incurred during the previous two decades. The money was mismanaged, though, by Joseph Slingerland. He spent about $500,000 on property purchases, improvements, and renovations, including building an ornate trustees' Office, now called Marble Hall. Contrary to Shaker practice, Slingerland mortgaged the Watervliet, Ohio, Shaker site to compensate for the expenditures and debt. Fennessey became a trustee and by 1902 had Slingerland removed from the Ohio ministry and filed suit against him and an eldress. By 1908 the Union Village ministry was free of debt. [18]

In 1898 Elder Oliver Hampton attempted to create a settlement in Georgia at White Oak to create momentum for the flagging endeavor. However, Hampton died while on a visit there, and with his death came the end to the new settlement. [19]

Hundreds joined the Shakers, who believed that Christ had already appeared for the second time in the person of Mother Ann Lee. The "Advents'" impact was greatest on the Shaker villages at Union Village and Whitewater, Ohio, Harvard, Massachusetts, and Canterbury, New Hampshire. Some remained Shakers for the rest of their lives; others left after a short time. [20]

In December 2004, United States Senator from Ohio, Rob Portman, and Cheryl Bauer published a book on the 19th century Shaker community at Union Village. The book was titled Wisdom's Paradise: The Forgotten Shakers of Union Village. At the end of the twelfth chapter, "An Eternal Sabbath, A Restless Peace," Portman summarizes the dual aspects of Shaker impacts at the close of their way of life at Union Village as both warming to mainstream worldly culture and detrimental to long established order:

Intentionally or unintentionally, the Believers were influencing society in many ways. Little by little, they were becoming more similar to their neighbors. The trend made them more acceptable to society, but in retrospect may have contributed to their demise in Warren County. In economic affairs, they increasingly adapted the methods of the world: taking out loans, using mass marketing techniques. Those strategies sometimes compromised inherent Shaker principles of self-sufficiency and modesty. The Believers were no longer the radical group that attracted people who hungered for a different kind of faith; they were becoming a part of mainstream society. [21]

The Lebanon Correctional Institution and the Warren Correctional Institution, which are adjacent to one another, were built upon land that had been part of the Shaker settlement.

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a millenarian restorationist Christian sect founded c. 1747 in England and then organized in the United States in the 1780s. They were initially known as "Shaking Quakers" because of their ecstatic behavior during worship services. Espousing egalitarian ideals, women took on spiritual leadership roles alongside men, including founding leaders such as Jane Wardley, Ann Lee, and Lucy Wright. The Shakers emigrated from England and settled in Revolutionary colonial America, with an initial settlement at Watervliet, New York, in 1774. They practice a celibate and communal utopian lifestyle, pacifism, uniform charismatic worship, and their model of equality of the sexes, which they institutionalized in their society in the 1780s. They are also known for their simple living, architecture, technological innovation, music, and furniture.

Patriot is a town in Posey Township, Switzerland County, in the U.S. state of Indiana, along the Ohio River. The population was 209 at the 2010 census.

James Whittaker was the second leader of the Shakers.

Canterbury Shaker Village is a historic site and museum in Canterbury, New Hampshire, United States. It was one of a number of Shaker communities founded in the 19th century.

Mount Lebanon Shaker Society, also known as New Lebanon Shaker Society, was a communal settlement of Shakers in New Lebanon, New York. The earliest converts began to "gather in" at that location in 1782 and built their first meetinghouse in 1785. The early Shaker Ministry, including Joseph Meacham and Lucy Wright, the architects of Shakers' gender-balanced government, lived there.

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village is a Shaker village near New Gloucester and Poland, Maine, in the United States. It is the last active Shaker community, with two members as of 2020. With a new member, it had expanded to three members by 2021. The community was established in either 1782, 1783, or 1793, at the height of the Shaker movement in the United States. The Sabbathday Lake meetinghouse was built in 1794. The entire property was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974.

The Enfield Shaker Museum is an outdoor history museum and historic district in Enfield, New Hampshire, in the United States. It is dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of the Shakers, a Protestant religious denomination, who lived on the site from 1793 to 1923. The museum features exhibitions, artifacts, eight Shaker buildings and restored Shaker gardens. It is located in a valley between Mount Assurance and Mascoma Lake in Enfield.

West Union (Busro) is an abandoned Shaker community in Busseron Township, northwestern Knox County, Indiana, about fifteen miles (24 km) north of Vincennes. The settlement was inhabited by the Shakers (United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing) from 1811 to 1827. Though short-lived, West Union was the westernmost Shaker settlement.

Lucy Wright was the leader of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, also known as the Shakers, from 1796 until 1821. At that time, a woman's leadership of a religious sect was a radical departure from Protestant Christianity.

The Enfield Shakers Historic District encompasses some of the surviving remnants of a former Shaker community in Enfield, Connecticut. Founded in the 1780s, the Enfield Shaker community remained active until 1917. The surviving buildings of their once large community complexes are located in and around Taylor Road in northeastern Enfield, and were listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The listing included 15 contributing buildings and one contributing site.

Alfred Shaker Historic District is a historic district in Alfred, Maine, with properties on both sides of Shaker Hill Road. The area had its first Shaker "believers" in 1783 following visiting with Mother Ann Lee and became an official community starting in 1793 when a meetinghouse was built. It was home to Maine's oldest and largest Shaker community. Two notable events were the songwriting of Joseph Brackett, including, according to most accounts, Simple Gifts, and the spiritual healing of the sick by the Shakers. When the Alfred Shakers products and goods were no longer competitive with mass-produced products and the membership had dwindled significantly, the village was closed in 1931 and members moved to Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, also in Maine.

The chronology of Shakers is a list of important events pertaining to the history of the Shakers, a denomination of Christianity. Millenarians who believe that their founder, Ann Lee, experienced the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, the Shakers practice celibacy, confession of sin, communalism, ecstatic worship, pacifism, and egalitarianism. This spans the emergence of denomination in the mid-18th century, the emigration of the Shakers to New York on the eve of the American Revolution, subsequent missionary work and the establishment of nineteen major planned communities, and the continued persistence of the faith through decline into the 21st century.

The Shakers are a sect of Christianity which practices celibacy, communal living, confession of sin, egalitarianism, and pacifism. After starting in England, it is thought that these communities spread into the cotton towns of North West England, with the football team of Bury taking on the Shaker name to acknowledge the Shaker community of Bury.The Shakers left England for the English colonies in North America in 1774. As they gained converts, the Shakers established numerous communities in the late-18th century through the entire 19th century. The first villages organized in Upstate New York and the New England states, and, through Shaker missionary efforts, Shaker communities appeared in the Midwestern states. Communities of Shakers were governed by area bishoprics and within the communities individuals were grouped into "family" units and worked together to manage daily activities. By 1836 eighteen major, long-term societies were founded, comprising some sixty families, along with a failed commune in Indiana. Many smaller, short-lived communities were established over the course of the 19th century, including two failed ventures into the Southeastern United States and an urban community in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Shakers peaked in population by the 1840s and early 1850s, with a membership between 4,000 and 9,000. Growth in membership began to stagnate by the mid 1850s. In the turmoil of the American Civil War and subsequent Industrial Revolution, Shakerism went into severe decline. As the number of living Shakers diminished, Shaker communes were disbanded or otherwise ceased to exist. Some of their buildings and sites have become museums, and many are historic districts under the National Register of Historic Places. The only active community is Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine, which is composed of at least three active members.

Groveland Shaker Village was a settlement of Shakers in Groveland, New York under the bishopric of Groveland.

Watervliet Shaker Village was a Shaker community located in Kettering, Ohio, from 1806 to 1900. Its spiritual name was Vale of Peace and it was within the Union Village bishopric, or governing body.

Drakes Creek is a stream in Warren County, Kentucky, in the United States. It is a tributary of the Barren River. Drakes Creek, as measured at Alvaton, has a mean annual discharge of 768 cubic feet per second. Drakes Creek was named for a white pioneer named Drake who narrowly escaped with his life an attack by Indians. The Shaker community of South Union, Kentucky, attempted a settlement along the creek, some 16 miles from their main village, in 1817, but the effort was abandoned in 1829.

Ruth Mildred Barker was a musician, scholar, manager, and spiritual leader from the Alfred and Sabbathday Lake Shaker villages. A prominent and respected Shaker during her long life, she worked to preserve Shaker music. With the help of Daniel Patterson, she recorded Early Shaker Spirituals, a collection of Shaker songs. In recognition of her achievements in the field, in 1983 she received the National Heritage Fellowship. She also co-founded and managed The Shaker Quarterly, a magazine and journal focused on the Shakers, to which she was also a regular contributor.

Minnie Catherine Allen was a leader among the Shakers, active as a historian and activist as well as a member of the Central Shaker Ministry.

Simon Tuttle Atherton was an early American Shaker, who became highly successful on behalf of his own community, in selling herbs in and around Boston, Massachusetts.

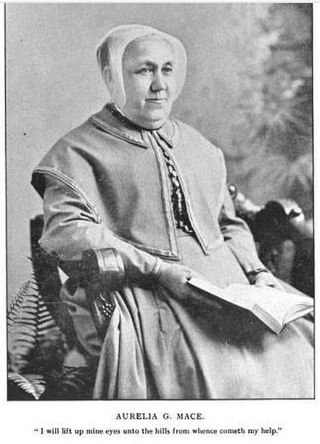

Aurelia Mace was a Shaker eldress, thinker, and writer. She is known for her letters and essays which were compiled into the book The Aletheia: Spirit of Truth.

Note: The Library of Congress, Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, Ohio, and Ohio Historical Society in Columbus, Ohio, own hundreds of Shaker manuscripts and journals that contain further historical information about Ohio Shakers.