Placement and importance within the Vercelli book

Though the Vercelli book contains, in addition to the homilies, six items written in verse, there seems to be little evidence of an overarching thought structure behind the arrangement of the items within the manuscript. The six verse items, rather than being separated from the prose homilies, are interspersed throughout, demonstrating little intentional differentiation between the prose and verse items of the manuscript. In keeping with the tradition of most Old English vernacular homilies, very little of the material within the Vercelli homilies appears to be original; the vast majority was most likely compiled by the Vercelli scribe from a single library over an extended period of time (Scragg, 1998). Many of the homilies, moreover, were translated very awkwardly into Old English from the original Latin, offering, in some cases, some difficult sections wherein the Old English seems to be based around flawed Latin translation. In fact, the few Latin quotations that appear throughout the homilies suggest that the Vercelli scribe had no training whatsoever in the language.

Subject matter and style

Though the homilies seem to have been gathered piecemeal with little concern for their relation to each other, there do seem to be connections between certain of the homilies. Homilies VI through X constitute a numbered series; XI through XIV seem to share a similar method of rubrication; the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first homilies are, most likely, by the same author. Additionally, the time origins of the homilies differ greatly. The first, second, and arguably third homilies seem to fit into the homiletic tradition of the early tenth century, making them the oldest prose within the Vercelli book; on the other hand, homilies XIX through XXI were most likely written very shortly before the collection of the Vercelli materials.

The subject matter of the homilies also differs considerably from example to example. The majority of the homilies are drawn from the period’s dominant Christian tradition. Homilies II, III, IV, VII, IX, X, XIV, XV, and XXII are eschatological in nature; common themes throughout this broad category of the homilies include descriptions of the End of the World and pleas for repentance in the face of impending judgment. This emphasis on judgment appears elsewhere within the homilies; homilies XI through XIII and XIX through XXI are both sets of three intended for the days leading into Ascension Day as a preparation for, on the third day, meeting God. Relatively few of the homilies are explanatory in nature. Homily I is, in essence, a copy of the Gospel’s story of the Passion, as it offers little comment in addition to the biblical text. Homilies V and VI explain the story of Christmas, while XVI describes the Epiphany and XVII Candlemas. Homilies XVIII and XXIII are the lives of Saints Martin and Guthlac respectively. Homily XXII resists some efforts to classify, as it is more of a spiritual contemplation exploring the fate of the soul after death than a typical homily.

The manner of transposition of the homilies differs greatly through the manuscript. As mentioned, many of the homilies are tied intrinsically to their original Latin, and rarely depart from a very textbook translation into Old English. Others appear to have been merely lifted verbatim from other vernacular texts; homily XXI, for instance, contains a word for word cop of parts of an early version of homily II. On the other hand, certain homilies seem to benefit from a very loose association with the original source material, and have been translated freely into Old English. Homily X has been especially praised as a “highly sophisticated creation” that “shows the application of a shrewd mind, one that can express ideas in highly wrought and beautiful language” (D.G. Scragg). Once again, however, it must be emphasized that the author of homily X, and the authors of all the homilies in general, are unknown, and were uninvolved in the inclusion of the homilies in the Vercelli Book (Scragg, The Vercelli homilies, 1992).

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating pertains to the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025. The anonymous poet is referred to by scholars as the "Beowulf poet".

Old English literature, or Anglo-Saxon literature, encompasses literature written in Old English, in Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066. "Cædmon's Hymn", composed in the 7th century, according to Bede, is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English. Poetry written in the mid-12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English; for example, The Soul's Address to the Body found in Worcester Cathedral Library MS F. 174 contains only one word of possible Latinate origin, while also maintaining a corrupt alliterative meter and Old English grammar and syntax, albeit in a degenerative state. The Peterborough Chronicle can also be considered a late-period text, continuing into the 12th century. The strict adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th century work – as is evident in the works cited above – and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Cynewulf is one of twelve Old English poets known by name, and one of four whose work is known to survive today. He presumably flourished in the 9th century, with possible dates extending into the late 8th and early 10th centuries.

Ælfric of Eynsham was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. He is also known variously as Ælfric the Grammarian, Ælfric of Cerne, and Ælfric the Homilist. In the view of Peter Hunter Blair, he was "a man comparable both in the quantity of his writings and in the quality of his mind even with Bede himself." According to Claudio Leonardi, he "represented the highest pinnacle of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature".

The Old English poem Judith describes the beheading of Assyrian general Holofernes by Israelite Judith of Bethulia. It is found in the same manuscript as the heroic poem Beowulf, the Nowell Codex, dated ca. 975–1025. The Old English poem is one of many retellings of the Holofernes–Judith tale as it was found in the Book of Judith, still present in the Catholic and Orthodox Christian Bibles. Most notably, Ælfric of Eynsham, late 10th-century Anglo-Saxon abbot and writer, composed a homily of the tale.

Wulfstan was an English Bishop of London, Bishop of Worcester, and Archbishop of York. He should not be confused with Wulfstan I, Archbishop of York, or Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester. He is thought to have begun his ecclesiastical career as a Benedictine monk. He became the Bishop of London in 996. In 1002 he was elected simultaneously to the diocese of Worcester and the archdiocese of York, holding both in plurality until 1016, when he relinquished Worcester; he remained archbishop of York until his death. It was perhaps while he was at London that he first became well known as a writer of sermons, or homilies, on the topic of Antichrist. In 1014, as archbishop, he wrote his most famous work, a homily which he titled the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or the Sermon of the Wolf to the English.

Saint Guthlac of Crowland was a Christian saint from Lincolnshire in England. He is particularly venerated in the Fens of eastern England.

Elizabeth Elstob, the "Saxon Nymph", was a pioneering scholar of Anglo-Saxon.

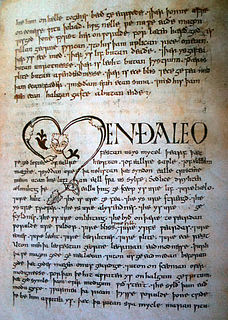

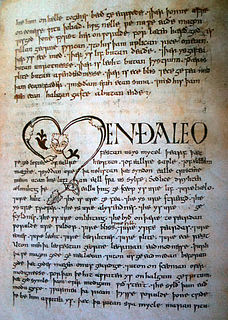

The Vercelli Book is one of the oldest of the four Old English Poetic Codices. It is an anthology of Old English prose and verse that dates back to the late 10th century. The manuscript is housed in the Capitulary Library of Vercelli, in northern Italy.

The Blickling Homilies is the name given to a collection of anonymous homilies from Anglo-Saxon England. They are written in Old English, and were written down at some point before the end of the tenth century, making them one of the oldest collections of sermons to survive from medieval England, the other main witness being the Vercelli Book. Their name derives from Blickling Hall in Norfolk, which once housed them; the manuscript is now Princeton, Scheide Library, MS 71.

Andreas is an Old English poem, which tells the story of St. Andrew the Apostle, while commenting on the literary role of the "hero". It is believed to be a translation of a Latin work, which is originally derived from the Greek story The Acts of Andrew and Matthew in the City of Anthropophagi, dated around the 4th century. However, the author of Andreas added the aspect of the Germanic hero to the Greek story to create the poem Andreas, where St. Andrew is depicted as an Old English warrior, fighting against evil forces. This allows Andreas to have both poetic and religious significance.

Christ and Satan is an anonymous Old English religious poem consisting of 729 verse lines, contained in the Junius Manuscript.

The Harrowing of Hell is an eighth-century Latin piece in fifty-five lines found in the Anglo-Saxon Book of Cerne. It is probably a Northumbrian piece, written in prose and verse, where the former serves either as a set of stage directions for a dramatic portrayal or as a series of narrations for explaining the poetry.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great. Multiple copies were made of that one original and then distributed to monasteries across England, where they were independently updated. In one case, the Chronicle was still being actively updated in 1154.

Cædmon's "Hymn" is a short Old English poem originally composed by Cædmon, a supposedly illiterate cow-herder who was, according to Bede, able to sing in honour of God the Creator, using words that he had never heard before. It was composed between 658 and 680 and is the oldest recorded Old English poem, being composed within living memory of the Christianization of Anglo-Saxon England. It is also one of the oldest surviving samples of Germanic alliterative verse.

Aldred the Scribe is the name by which scholars identify a tenth-century priest, otherwise known only as Aldred, who was a provost of the monastic community of St. Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street in 970.

The Toller Lecture is an annual lecture at the University of Manchester's Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies (MANCASS). It is named after Thomas Northcote Toller, one of the editors of An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.

The Old English Boethius is an Old English translation/adaptation of the sixth-century Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, dating from between c. 880 and 950. Boethius's work is prosimetrical, alternating between prose and verse, and one of the two surviving manuscripts of the Old English translation renders the poems as Old English alliterative verse: these verse translations are known as the Metres of Boethius.