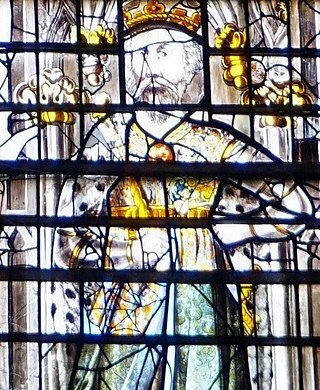

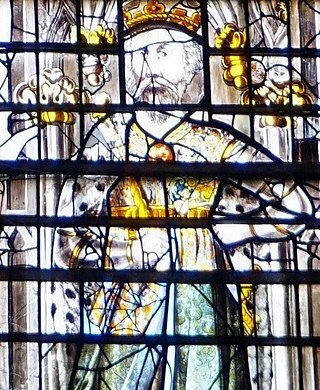

Offa was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of Æthelbald. Offa defeated the other claimant, Beornred. In the early years of Offa's reign, it is likely that he consolidated his control of Midland peoples such as the Hwicce and the Magonsæte. Taking advantage of instability in the kingdom of Kent to establish himself as overlord, Offa also controlled Sussex by 771, though his authority did not remain unchallenged in either territory. In the 780s he extended Mercian Supremacy over most of southern England, allying with Beorhtric of Wessex, who married Offa's daughter Eadburh, and regained complete control of the southeast. He also became the overlord of East Anglia and had King Æthelberht II of East Anglia beheaded in 794, perhaps for rebelling against him.

Eadwig was King of England from 23 November 955 until his death. He was the elder son of Edmund I and his first wife Ælfgifu, who died in 944. Eadwig and his brother Edgar were young children when their father was killed trying to rescue his seneschal from attack by an outlawed thief on 26 May 946. As Edmund's sons were too young to rule he was succeeded by his brother Eadred, who suffered from ill health and died unmarried in his early 30s.

Æthelred I was King of Wessex from 865 until his death in 871. He was the fourth of five sons of King Æthelwulf of Wessex, four of whom in turn became king. Æthelred succeeded his elder brother Æthelberht and was followed by his youngest brother, Alfred the Great. Æthelred had two sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold, who were passed over for the kingship on their father's death because they were still infants. Alfred was succeeded by his son, Edward the Elder, and Æthelwold unsuccessfully disputed the throne with him.

Edward the Martyr was King of England from 8 July 975 until he was killed on 18 March 978. He was the eldest son of King Edgar (959–975). On Edgar's death, the succession to the throne was contested between Edward's supporters and those of his younger half-brother, the future King Æthelred the Unready. As they were both children, it is unlikely that they played an active role in the dispute, which was probably between rival family alliances. Edward's principal supporters were Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury and Æthelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia, while Æthelred was backed by his mother, Queen Ælfthryth and her friend Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester. The dispute was quickly settled. Edward was chosen as king and Æthelred received the lands traditionally allocated to the king's eldest son in compensation.

Æthelbald was the King of Mercia, in what is now the English Midlands from 716 until he was killed in 757. Æthelbald was the son of Alweo and thus a grandson of King Eowa. Æthelbald came to the throne after the death of his cousin, King Ceolred, who had driven him into exile. During his long reign, Mercia became the dominant kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons, and recovered the position of pre-eminence it had enjoyed during the strong reigns of Mercian kings Penda and Wulfhere between about 628 and 675.

Coenwulf was the King of Mercia from December 796 until his death in 821. He was a descendant of King Pybba, who ruled Mercia in the early 7th century. He succeeded Ecgfrith, the son of Offa; Ecgfrith only reigned for five months, and Coenwulf ascended the throne in the same year that Offa died. In the early years of Coenwulf's reign he had to deal with a revolt in Kent, which had been under Offa's control. Eadberht Præn returned from exile in Francia to claim the Kentish throne, and Coenwulf was forced to wait for papal support before he could intervene. When Pope Leo III agreed to anathematise Eadberht, Coenwulf invaded and retook the kingdom; Eadberht was taken prisoner, was blinded, and had his hands cut off. Coenwulf also appears to have lost control of the kingdom of East Anglia during the early part of his reign, as an independent coinage appears under King Eadwald. Coenwulf's coinage reappears in 805, indicating that the kingdom was again under Mercian control. Several campaigns of Coenwulf's against the Welsh are recorded, but only one conflict with Northumbria, in 801, though it is likely that Coenwulf continued to support the opponents of the Northumbrian king Eardwulf.

Ine, also rendered Ini or Ina, was King of Wessex from 689 to 726. At Ine's accession, his kingdom dominated much of southern England. However, he was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla, who had expanded West Saxon territory substantially. By the end of Ine's reign, the kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, and Essex were no longer under West Saxon sway; however, Ine maintained control of what is now Hampshire, and consolidated and extended Wessex's territory in the western peninsula.

Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians became ruler of English Mercia shortly after the death or disappearance of its last king, Ceolwulf II in 879. Æthelred's rule was confined to the western half, as eastern Mercia was then part of the Viking-ruled Danelaw. His ancestry is unknown. He was probably the leader of an unsuccessful Mercian invasion of Wales in 881, and soon afterwards he acknowledged the lordship of King Alfred the Great of Wessex. This alliance was cemented by the marriage of Æthelred to Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd.

Æthelwold or Æthelwald was the younger of two known sons of Æthelred I, King of Wessex from 865 to 871. Æthelwold and his brother Æthelhelm were still infants when their father the king died while fighting a Danish Viking invasion. The throne passed to the king's younger brother Alfred the Great, who carried on the war against the Vikings and won a crucial victory at the Battle of Edington in 878.

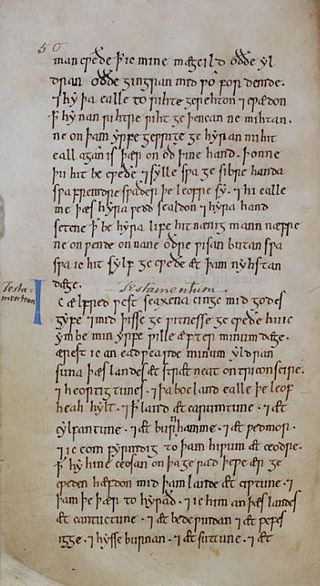

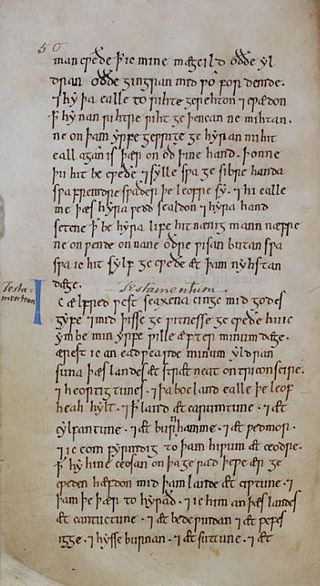

Ælfgifu was Queen of the English as wife of King Eadwig of England for a brief period of time until 957 or 958. What little is known of her comes primarily by way of Anglo-Saxon charters, possibly including a will, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and hostile anecdotes in works of hagiography. Her union with the king, annulled within a few years of Eadwig's reign, seems to have been a target for factional rivalries which surrounded the throne in the late 950s. By c. 1000, when the careers of the Benedictine reformers Dunstan and Oswald became the subject of hagiography, its memory had suffered heavy degradation. In the mid-960s, however, she appears to have become a well-to-do landowner on good terms with King Edgar and, through her will, a generous benefactress of ecclesiastical houses associated with the royal family, notably the Old Minster and New Minster at Winchester.

Æthelhelm or Æþelhelm was the elder of two known sons of Æthelred I, King of Wessex from 865 to 871, and Queen Wulfthryth.

The ancient Selwood Forest ran approximately between Gillingham in Dorset and Chippenham in Wiltshire. It is described by the historian Barbara Yorke as a "formidable natural obstacle" in the Anglo-Saxon period, which was a significant boundary between east and west Wessex. It may earlier have been a negotiated frontier between Wessex and the British kingdom of Dumnonia which was important in the later development of the West Saxon shires, and later boundaries between Wiltshire and Somerset and north Dorset run through the forest. The boundaries through the forest and Bokerley Dyke which separated Somerset and Dorset from eastern counties may date to the fifth or sixth centuries. Selwood's importance as a boundary was also recognised in 705 when the bishopric of Sherborne was established for those "west of Selwood".

Edward the Elder was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a challenge from his cousin Æthelwold, who had a strong claim to the throne as the son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor, Æthelred I.

Thored was a 10th-century Ealdorman of York, ruler of the southern half of the old Kingdom of Northumbria on behalf of the king of England. He was the son of either Gunnar or Oslac, northern ealdormen. If he was the former, he may have attained adulthood by the 960s, when a man of his name raided Westmorland. Other potential appearances in the records are likewise uncertain until 979, the point from which Thored's period as ealdorman can be accurately dated.

Ælfhelm was the ealdorman of Northumbria, in practice southern Northumbria, from about 994 until his death. An ealdorman was a senior nobleman who governed a province—a shire or group of shires—on behalf of the king. Ælfhelm's powerful and wealthy family came from Mercia, a territory and former kingdom incorporating most of central England, and he achieved his position despite being an outsider. Ælfhelm first appears in charters as dux ("ealdorman") in about 994.

Northman was a Mercian chieftain of the early 11th century. A member of a powerful Mercian kinship (clan), he is known primarily for receiving the village of Twywell in Northamptonshire from King Æthelred II in 1013, and for his death by order of King Cnut the Great (Canute) in 1017. His violent end by Cnut contrasts with the successful career enjoyed by his brother Leofric, as Earl of Mercia during Cnut's reign. Northman is believed to have been an associate of the troublesome ealdorman Eadric Streona, who was killed with him.

Very little is known for certain of the ancestry of the Godwins, the family of the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, Harold II. When King Edward the Confessor died in January 1066 his closest relative was his great-nephew, Edgar the Ætheling, but he was young and lacked powerful supporters. Harold was the head of the most powerful family in England and Edward's brother-in-law, and he became king. In September 1066 Harold defeated and killed King Harald Hardrada of Norway at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, and Harold was himself defeated and killed the following month by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings.

Æthelred Mucel was an Anglo-Saxon noble from Mercia who was the father of Ealhswith, the wife of Alfred the Great.

Osferth or Osferd or Osfrith was described by Alfred the Great in his will as a "kinsman". Osferth witnessed royal charters from 898 to 934, as an ealdorman between 926 and 934. In a charter of Edward the Elder, he was described as a brother of the king. Therefore, Janet Nelson argues that he was probably an illegitimate son of Alfred. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge suggest that he may have been a relative of Alfred's mother Osburh, or a son of Oswald filius regis, who in turn may have been a son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor as king, Æthelred I.

Cyfeilliog was Bishop of Ergyng and probably Gwent in south-east Wales. He is recorded by the mid-880s in the Llandaff Charters and in 914 he was captured by the Vikings and ransomed by Edward the Elder, King of the Anglo-Saxons, for 40 pounds. He is probably the author of a cryptogram in the Juvencus Manuscript which would have required a knowledge of Latin and Greek.