Related Research Articles

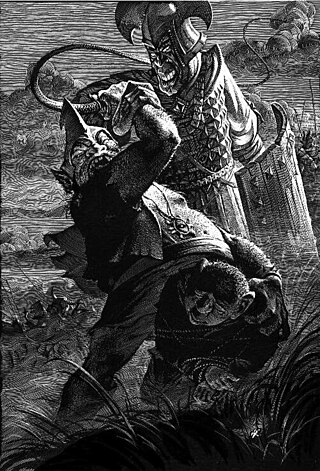

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating is for the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025 AD. Scholars call the anonymous author the "Beowulf poet". The story is set in pagan Scandinavia in the 5th and 6th centuries. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall Heorot has been under attack by the monster Grendel for twelve years. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother takes revenge and is in turn defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a barrow on a headland in his memory.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Rohan is a fictional kingdom of Men in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy setting of Middle-earth. Known for its horsemen, the Rohirrim, Rohan provides its ally Gondor with cavalry. Its territory is mainly grassland. The Rohirrim call their land the Mark or the Riddermark, names recalling that of the historical kingdom of Mercia, the region of Western England where Tolkien lived.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

"Deor" is an Old English poem found on folio 100r–100v of the late-10th-century collection the Exeter Book. The poem consists of a reflection on misfortune by a poet whom the poem is usually thought to name Deor. The poem has no title in the Exeter Book itself; the title has been bestowed by modern editors.

The Peterborough Chronicle is a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles originally maintained by the monks of Peterborough Abbey, now in Cambridgeshire. It contains unique information about the history of England and of the English language after the Norman Conquest; according to philologist J. A. W. Bennett, it is the only prose history in English between the Conquest and the later 14th century.

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has survived.

The Proverbs of Alfred is a collection of early Middle English sayings ascribed to King Alfred the Great, said to have been uttered at an assembly in Seaford, East Sussex. The collection of proverbs was probably put together in Sussex in the mid-12th century. The manuscript evidence suggests the text originated at either a Cluniac or a Benedictine monastery: either Lewes Priory, 10 mi (16 km) to the north of Seaford, or Battle Abbey, 25 mi (40 km) to the north-east.

Northumbrian was a dialect of Old English spoken in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria. Together with Mercian, Kentish and West Saxon, it forms one of the sub-categories of Old English devised and employed by modern scholars.

The Battle of Aylesford or Epsford was fought between Britons and Anglo-Saxons recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Historia Brittonum. Both sources concur that it involved the Anglo-Saxon leaders Hengist and Horsa on one side and the family of Vortigern on the other, but neither says who won the battle. It was fought near Æglesthrep, presumed to be Aylesford, in Kent.

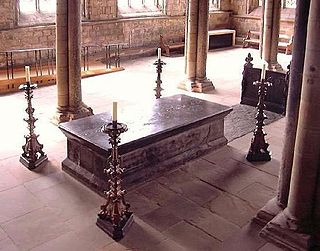

Saint Sigfrid of Sweden (Swedish: Sigfrid, Latin: Sigafridus, Old Norse: Sigurðr, Old English: Sigefrið/Sigeferð) was a missionary-bishop in Scandinavia during the first half of the 11th century. Originally from England, Saint Sigfrid is credited in late medieval king-lists and hagiography with performing the baptism of the first steadfastly Christian monarch of Sweden, Olof Skötkonung. He most likely arrived in Sweden soon after the year 1000 and conducted extensive missions in Götaland and Svealand. For some years after 1014, following his return to England, Sigfrid was based in Trondheim, Norway. However, his position there became untenable after the defeat of Olaf Haraldsson.

"Maxims I" and "Maxims II" are pieces of Old English gnomic poetry. The poem "Maxims I" can be found in the Exeter Book and "Maxims II" is located in a lesser known manuscript, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B i. "Maxims I" and "Maxims II" are classified as wisdom poetry, being both influenced by wisdom literature, such as the Havamal of ancient Germanic literature. Although they are separate poems of diverse contents, they have been given a shared name because the themes throughout each of the poems are similar.

In Germanic paganism, a vé or wēoh is a type of shrine, sacred enclosure or other place with religious significance. The term appears in skaldic poetry and in place names in Scandinavia, often in connection with an Old Norse deity or a geographic feature.

De falsis diis, or, in Classical Latin spelling, De falsis deis, is an Old English homily composed by Ælfric of Eynsham in the late tenth or early eleventh century. The sermon is noted for its attempt to explain beliefs in traditional Anglo-Saxon and Norse gods within a Christian framework through Euhemerisation. The homily was subsequently adapted and circulated by Wulfstan II, Archbishop of York, and also translated into Old Norse under the title ''Um þat hvaðan ótrú hófsk''.

Langfeðgatal is an anonymous, twelfth-century Icelandic genealogy of Scandinavian kings.

Bede's Death Song is the editorial name given to a five-line Old English poem, supposedly the final words of the Venerable Bede. It is, by far, the Old English poem that survives in the largest number of manuscripts — 35 or 45. It is found in both Northumbrian and West Saxon dialects.

The Old English Dicts of Cato is the editorial name given to the Old English language text based on the Latin Distichs of Cato. It is a collection of approximately 80 prose proverbs, the exact number varying between each of the three manuscript versions. These can be found in MS Cambridge, Trinity College, R.9.17, MS British Library, Cotton Vespasian D.xiv and MS British Library, Cotton Julius A.ii respectively.

Leonard Neidorf is an American philologist who is Distinguished Professor of English at Shenzhen University. Neidorf specializes in the study of Old English and Middle English literature, and is a known authority on Beowulf.

The Proverbia Grecorum is an anonymous Latin collection of proverbs compiled in the seventh or eighth century AD in the British Isles, probably in Ireland. Despite the name, it has no known Greek source. It was perhaps designed as a secular complement to the Hebrew Bible's Book of Proverbs.

The author J. R. R. Tolkien uses many proverbs in The Lord of the Rings to create a feeling that the world of Middle-earth is both familiar and solid, and to give a sense of the different cultures of the Hobbits, Men, Elves, and Dwarves who populate it. Scholars have also commented that the proverbs are sometimes used directly to portray characters such as Barliman Butterbur, who never has time to collect his thoughts. Often these proverbs serve to make Tolkien's created world seem at once real and solid, while also remaining somewhat unfamiliar. Further, the proverbs help to convey Tolkien's underlying message about providence; while he keeps his Christianity hidden, readers can see that what appears as luck to the protagonists reflects a higher purpose throughout Tolkien's narrative.

References

- 1 2 Milfull 1996, pp. 34.

- ↑ Hollis & Wright 1992, pp. 34.

- ↑ Springer 1995, pp. 129.

- ↑ Hollis & Wright 1992, pp. 35.

- 1 2 Marsden 2004, pp. 302–303.

- 1 2 Marsden 2004, pp. 302.

- 1 2 Arngart 1981, pp. 288.

- ↑ Arngart 1981, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Treharne 2003, pp. 470–471.

- ↑ Treharne 2003, pp. 468.

- ↑ Poole 1998, pp. 207.

- ↑ Laingui 1997, pp. 929.

- ↑ Arngart 1981, pp. 289.

- ↑ Arngart 1981, pp. 290.

- ↑ Greenfield, Calder & Lapidge 1996, pp. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fulk, Cain & Anderson 2003, pp. 167.

- ↑ Arngart 1981, pp. 296.

- 1 2 Marsden 2004, pp. 306.

- 1 2 Robinson 1982, pp. 4, 262.

- ↑ Arngart 1981, pp. 293.

- ↑ Abels 2006, pp. 34–35.

- 1 2 Gwara 2008, pp. 94.

- ↑ Hollis & Wright 1992, pp. 47.

- ↑ Sánchez-Martí 2008, pp. 218.

- ↑ Sánchez-Martí 2008, pp. 217.

Bibliography

- Abels, Richard (2006). ""Cowardice" and Duty in Anglo-Saxon England". In Clifford J. Rogers; Kelly DeVries; John France (eds.). The journal of medieval military history. Vol. 4. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-267-6.

- Arngart, Olof Sigfrid (April 1981). "The Durham Proverbs". Speculum. 56 (2): 288–300. doi:10.2307/2846936. JSTOR 2846936. S2CID 163063785.

- Fulk, Robert Dennis; Cain, Christopher M.; Anderson, Rachel S. (2003). "Wisdom Literature and Lyric Poetry". A history of Old English literature. Blackwell histories of literature. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22397-9.

- Gwara, Scott (2008). Heroic identity in the world of Beowulf. Medieval and Renaissance authors and texts. Vol. 2. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17170-1.

- Greenfield, Stanley B.; Calder, Daniel Gillmore; Lapidge, Michael (1996). "Ælfric, Wulfstan, and other Late prose". A New Critical History of Old English Literature. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3088-1.

- Hollis, Stephanie; Wright, Michael (1992). "Durham and other Proverbs". Old English prose of secular learning . Annotated bibliographies of Old and Middle English literature. Vol. 4. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85991-343-0.

- Laingui, André (1997). "Maxim". In Andre Vauchez (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. ISBN 978-1-57958-282-1.

- Marsden, Richard (2004). "The Durham Proverbs". The Cambridge Old English Reader. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45612-8.

- Milfull, Inge B. (1996). The hymns of the Anglo-Saxon church: a study and edition of the Durham Hymnal. Cambridge studies in Anglo-Saxon England. Vol. 17. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46252-5.

- Poole, Russell Gilbert (1998). Old English wisdom poetry. Annotated bibliographies of Old and Middle English literature. Vol. 5. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85991-530-4.

- Robinson, Fred C. (1982). "Understanding an Old English Wisdom Verse: Maxims II, Lines 10ff". In Benson, Larry Dean; Wenzel, Siegfried (eds.). The Wisdom of poetry: essays in early English literature in honor of Morton W. Bloomfield. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. ISBN 978-0-918720-15-3.

- Sánchez-Martí, Jordi (2008). "Age Matters in Old English Literature". In Shannon Lewis-Simpson (ed.). Youth and age in the medieval north. The Northern World. Vol. 42. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17073-5.

- Springer, Carl P. E. (1995). "Manuscripts containing fragments, hymns, et al.". The manuscripts of Sedulius: a provisional handlist. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 85. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-855-1.

- Treharne, Elaine M. (October 2003). "The Form and Function of the Twelfth-Century Old English Dicts of Cato". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 102 (4): 465–485. JSTOR 27712374.