Beowulf is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating is for the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025. Scholars call the anonymous author the "Beowulf poet". The story is set in pagan Scandinavia in the 6th century. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall Heorot has been under attack by the monster Grendel for twelve years. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother takes revenge and is in turn defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a barrow on a headland in his memory.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Rohan is a fictional kingdom of Men in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy setting of Middle-earth. Known for its horsemen, the Rohirrim, Rohan provides its ally Gondor with cavalry. Its territory is mainly grassland. The Rohirrim call their land the Mark or the Riddermark, names recalling that of the historical kingdom of Mercia, the region of Western England where Tolkien lived.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word in the elvish language Sindarin, which Tolkien invented.

"Widsith", also known as "The Traveller's Song", is an Old English poem of 143 lines. It survives only in the Exeter Book, a manuscript of Old English poetry compiled in the late-10th century, which contains approximately one-sixth of all surviving Old English poetry. "Widsith" is located between the poems "Vainglory" and "The Fortunes of Men". Since the donation of the Exeter Book in 1076, it has been housed in Exeter Cathedral in southwestern England. The poem is for the most part a survey of the people, kings, and heroes of Europe in the Heroic Age of Northern Europe.

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has survived.

The Wanderer is an Old English poem preserved only in an anthology known as the Exeter Book, a manuscript dating from the late 10th century. It comprises 115 lines of alliterative verse. As is often the case with Anglo-Saxon verse, the composer and compiler are anonymous, and within the manuscript the poem is untitled.

The Seafarer is an Old English poem giving a first-person account of a man alone on the sea. The poem consists of 124 lines, followed by the single word "Amen". It is recorded only at folios 81 verso – 83 recto of the tenth-century Exeter Book, one of the four surviving manuscripts of Old English poetry. It has most often, though not always, been categorised as an elegy, a poetic genre commonly assigned to a particular group of Old English poems that reflect on spiritual and earthly melancholy.

"Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" was a 1936 lecture given by J. R. R. Tolkien on literary criticism on the Old English heroic epic poem Beowulf. It was first published as a paper in the Proceedings of the British Academy, and has since been reprinted in many collections.

"On Translating Beowulf" is an essay by J. R. R. Tolkien which discusses the difficulties faced by anyone attempting to translate the Old English heroic-elegiac poem Beowulf into modern English. It was first published in 1940 as a preface contributed by Tolkien to a translation of Old English poetry; it was first published as an essay under its current name in the 1983 collection The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays.

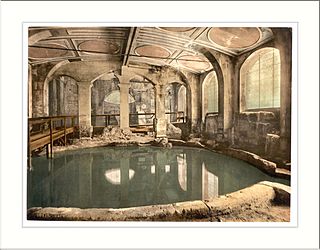

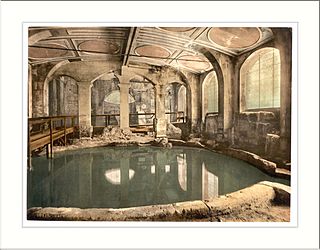

"The Ruin" is an elegy in Old English, written by an unknown author probably in the 8th or 9th century, and published in the 10th century in the Exeter Book, a large collection of poems and riddles. The poem evokes the former glory of an unnamed ruined ancient city that some scholars have identified with modern Bath, juxtaposing the grand, lively past with the decaying present.

"The Fortunes of Men", also "The Fates of Men" or "The Fates of Mortals", is the title given to an Old English gnomic poem of 98 lines in the Exeter Book, fols. 87a–88b.

The Durham Proverbs is a collection of 46 mediaeval proverbs from various sources. They were written down as a collection, in the eleventh century, on some pages of a manuscript that were originally left blank. The manuscript is currently in the collection of Durham Cathedral, to which it was donated in the eighteenth century. The Proverbs form the first part of the manuscript. The second part, to which it is bound, is a copy of Ælfric's Grammar. Each proverb is written in both Latin and Old English, with the former preceding the latter. Olof Arngart's opinion is that the Proverbs were originally in Old English and translated to Latin, but this has since been disputed in a conference paper by T. A. Shippey.

Beowulf: A New Verse Translation is a verse translation of the Old English epic poem Beowulf into modern English by the Irish poet and playwright Seamus Heaney. It was published in 1999 by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux and Faber and Faber, and won that year's Whitbread Book of the Year Award.

Leonard Neidorf is an American philologist who is Professor of English at Nanjing University. Neidorf specializes in the study of Old English and Middle English literature, and is a known authority on Beowulf.

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings; it appears, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden; in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.

The difficulty of translating Beowulf from its compact, metrical, alliterative form in a single surviving but damaged Old English manuscript into any modern language is considerable, matched by the large number of attempts to make the poem approachable, and the scholarly attention given to the problem.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a fantasy author and professional philologist, drew on the Old English poem Beowulf for multiple aspects of his Middle-earth legendarium, alongside other influences. He used elements such as names, monsters, and the structure of society in a heroic age. He emulated its style, creating an impression of depth and adopting an elegiac tone. Tolkien admired the way that Beowulf, written by a Christian looking back at a pagan past, just as he was, embodied a "large symbolism" without ever becoming allegorical. He worked to echo the symbolism of life's road and individual heroism in The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien was attracted to medieval literature, and made use of it in his writings, both in his poetry, which contained numerous pastiches of medieval verse, and in his Middle-earth novels where he embodied a wide range of medieval concepts.