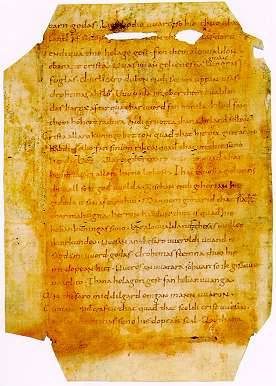

Christ and Satan is an anonymous Old English religious poem consisting of 729 lines of alliterative verse, contained in the Junius Manuscript, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Christ and Satan is an anonymous Old English religious poem consisting of 729 lines of alliterative verse, contained in the Junius Manuscript, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

The poem is located in a codex of Old English biblical poetry called the Junius Manuscript. The Junius Manuscript consists of two booklets, referred to as Book I and Book II, and it contains an assortment of illustrations. Book I of the Junius Manuscript houses the poems Genesis A , Genesis B , Exodus , and Daniel , while Book II holds Christ and Satan, the last poem in the manuscript.

Francis Junius was the first to credit Cædmon, the 7th century Anglo-Saxon religious poet, as the author of the manuscript. Junius was not alone in suggesting that Cædmon was the author of the manuscript, as many others noticed the “book’s collective contents strikingly resembled the body of work ascribed by Bede to the oral poet Cædmon” (Remley 264). However, the inconsistencies between Book I and Book II has made Christ and Satan a crucial part of the debate over the authorship of the manuscript. Most scholars now believe the Junius Manuscript to have been written by multiple authors. One piece of evidence that has called the authorship of the manuscript into question is the fact that unlike Genesis A and Genesis B, the complaints of Satan and the fallen angels (in the Book II poem Christ and Satan) are not made against God the Father, but rather Jesus the Son. [1] This variance is just one example of why the authorship of the manuscript is under suspicion. Another cause for suspicion is the opinion that Satan is portrayed “as a much more abject and pathetic figure [in Christ and Satan] than, for example in Genesis B”. [1] Furthermore, a single scribe is responsible for having copied out Genesis, Exodus, and Daniel, but Book II (consisting only of Christ and Satan) was entered “by three different scribes with rounder hands”. [2]

Unlike the poems in Book I of the Junius manuscript, which rely on Old Testament themes, Christ and Satan encompasses all of biblical history, linking both the Old Testament and New Testament, and expounding upon a number of conflicts between Christ and Satan. [1]

The composite and inconsistent nature of the text has been and remains some cause for confusion and debate. [3] Nevertheless, Christ and Satan is usually divided into three narrative sections:

In addition, the poem is interspersed with homiletic passages pleading for a righteous life and the preparation for Judgment Day and the afterlife. The value of the threefold division has not gone uncontested. Scholars such as Donald Scragg have questioned whether Christ and Satan should be read as one poem broken into three sections or many more poems which may or may not be closely interlinked. In some cases, such as in the sequence of Resurrection, Ascension and Day of Judgment, the poem does follow some logical narrative order. [4]

Due to the wide variety of topics in the text, scholars debate as to what constitute the main themes. Prevalent topics discussed, however, are 1) Satan as a character; 2) The might and measure of Christ and Satan (Christ vs. Satan: struggle for power) and 3) A search for Christ and Satan's self and identity (Christ vs. Satan: struggle for self). [5]

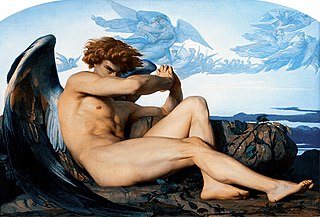

Old English authors often shied away from overtly degrading the devil. [6] In comparison, Christ and Satan humiliates, condemns, and de-emphasizes Satan versus Christ, holding him as the epic enemy and glorious angel. [7] The text portrays Satan as a narrative character, giving him long monologues in the "Fall of Satan" and the "Harrowing of Hell", where he is seen as flawed, failing, angry, and confused. In combining another predominant theme (see Christ vs. Satan: Struggle for Identity), Satan confuses and lies about his own self-identity, with his demons lamenting in hell saying,

In addition, Christ and Satan is one of the Old English pieces to be included in “The Plaints of Lucifer”. [8] The “Plaints” are pieces where Satan participates in human context and action and is portrayed as flawed, tormented, and ultimately weak, others including Phoenix , Guthlac , and “incidentally” in Andreas , Elene , Christ I and Christ II , Juliana , and in some manners of phraseology in Judith . [9] In comparison with other literature of the time period which portrayed Satan as the epic hero (such as Genesis A and B), the “Plaints” seem to have become much more popular historically, with a large number of plaintive texts surviving today. [10]

The power struggle between the two key characters in Christ and Satan is emphasized through context, alliteration, and theme; with a heavy emphasis on the great measure (ametan) of God. From the very beginning of the piece, the reader is reminded and expected to know the power and mightiness of God, the creator of the universe:

In all three parts of Christ and Satan, Christ's might is triumphant against Satan and his demons. [11] Alliteration combines and emphasizes these comparisons. The two words metan "meet" and ametan "measure" play with Satan's measuring of hell and his meeting of Christ, [12] caritas and cupiditas, [13] are compared between Christ and Satan, the micle mihte "great might" of God is mentioned often, and wite "punishment", witan "to know", and witehus "hell" [14] coincide perfectly with Satan's final knowledge that he will be punished to hell (the Fall of Satan). In the Temptation, truth and lies are compared between Christ and Satan explicitly through dialogue and recitation of scripture. Although both characters quote scripture, Christ is victorious in the end with a true knowledge of the word of God. The ending of The Temptation in Christ and Satan deviates from Biblical account. Actual scripture leaves the ending open with the sudden disappearance of Satan (Matthew 4:1-11), but Christ and Satan takes the more fictional and epic approach with a victory for Christ over Satan—adding to what scripture seems to have left to interpretation.

The word seolf "self" occurs over 22 times in the poem, [15] leaving scholars to speculate about the thematic elements of self-identity within the piece. Satan confuses himself with God and deceives his demons into believing that he is the ultimate Creator, while the seolf of Christ is emphasized many times throughout the piece. In the wilderness (Part III, the Temptation of Christ), Satan attacks Christ by questioning his identity and deity, [16] saying:

and

Christ finishes triumphantly, however, by banishing Satan to punishment and hell, manifesting his ability to banish the devil and revealing the true identities of himself and Satan. [17]

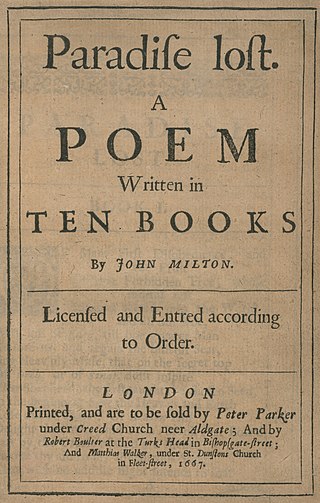

The poems of the Junius Manuscript, especially Christ and Satan, can be seen as a precursor to John Milton's 17th-century epic poem Paradise Lost. It has been proposed that the poems of the Junius Manuscript served as an influence of inspiration to Milton's epic, but there has never been enough evidence to prove such a claim (Rumble 385).

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books with minor revisions throughout. It is considered to be Milton's masterpiece, and it helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of all time. The poem concerns the biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in the course of a dream, according to the 8th-century Christian historian and saint Bede. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational Christian poet. He is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism, with a feast day on 11 February.

TheDream of the Rood is one of the Christian poems in the corpus of Old English literature and an example of the genre of dream poetry. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative verse. The word Rood is derived from the Old English word rōd 'pole', or more specifically 'crucifix'. Preserved in the tenth-century Vercelli Book, the poem may be as old as the eighth-century Ruthwell Cross, and is considered one of the oldest extant works of Old English literature.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Cynewulf is one of twelve Old English poets known by name, and one of four whose work is known to survive today. He presumably flourished in the 9th century, with possible dates extending into the late 8th and early 10th centuries.

Paradise Regained is a poem by English poet John Milton, first published in 1671. The volume in which it appeared also contained the poet's closet drama Samson Agonistes. Paradise Regained is connected by name to his earlier and more famous epic poem Paradise Lost, with which it shares similar theological themes; indeed, its title, its use of blank verse, and its progression through Christian history recall the earlier work. However, this effort deals primarily with the temptation of Christ as recounted in the Gospel of Luke.

The Junius manuscript is one of the four major codices of Old English literature. Written in the 10th century, it contains poetry dealing with Biblical subjects in Old English, the vernacular language of Anglo-Saxon England. Modern editors have determined that the manuscript is made of four poems, to which they have given the titles Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, and Christ and Satan. The identity of their author is unknown. For a long time, scholars believed them to be the work of Cædmon, accordingly calling the book the Cædmon manuscript. This theory has been discarded due to the significant differences between the poems.

The Heliand is an epic alliterative verse poem in Old Saxon, written in the first half of the 9th century. The title means "savior" in Old Saxon, and the poem is a Biblical paraphrase that recounts the life of Jesus in the alliterative verse style of a Germanic epic. Heliand is the largest known work of written Old Saxon.

The Questions of Bartholomew is not to be confused with the book called Resurrection of Jesus Christ, although either text may be the missing Gospel of Bartholomew, a lost work from the New Testament apocrypha.

The Ruthwell Cross is a stone Anglo-Saxon cross probably dating from the 8th century, when the village of Ruthwell, now in Scotland, was part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria.

Franciscus Junius , also known as François du Jon, was a pioneer of Germanic philology. As a collector of ancient manuscripts, he published the first modern editions of a number of important texts. In addition, he wrote the first comprehensive overview of ancient writings on the visual arts, which became a cornerstone of classical art theories throughout Europe.

Genesis A is an Old English poetic adaptation of about the first half of the biblical book of Genesis. The poem is fused with a passage known today as Genesis B, translated and interpolated from the Old Saxon Genesis.

Genesis B, also known as The Later Genesis, is a passage of Old English poetry describing the Fall of Satan and the Fall of Man, translated from an Old Saxon poem known as the Old Saxon Genesis. The passage known as Genesis B survives as an interpolation in a much longer Old English poem, the rest of which is known as Genesis A, which gives an otherwise fairly faithful translation of the biblical Book of Genesis. Genesis B comprises lines 235-851 of the whole poem.

In Christianity, the Devil is the personification of evil. He is traditionally held to have rebelled against God in an attempt to become equal to God himself. He is said to be a fallen angel, who was expelled from Heaven at the beginning of time, before God created the material world, and is in constant opposition to God. The devil is conjectured to be several other figures in the Bible including the serpent in the Garden of Eden, Lucifer, Satan, the tempter of the Gospels, Leviathan, and the dragon in the Book of Revelation.

Christ II, also called The Ascension, is one of Cynewulf's four signed poems that exist in the Old English vernacular. It is a five-section piece that spans lines 440–866 of the Christ triad in the Exeter Book, and is homiletic in its subject matter in contrast to the martyrological nature of Juliana, Elene, and Fates of the Apostles. Christ II draws upon a number of ecclesiastical sources, but it is primarily framed upon Gregory the Great’s Homily XXIX on Ascension Day.

Andreas is an Old English poem, which tells the story of St. Andrew the Apostle, while commenting on the literary role of the "hero". It is believed to be a translation of a Latin work, which is originally derived from the Greek story The Acts of Andrew and Matthew in the City of Anthropophagi, dated around the 4th century. However, the author of Andreas added the aspect of the Germanic hero to the Greek story to create the poem Andreas, where St. Andrew is depicted as an Old English warrior, fighting against evil forces. This allows Andreas to have both poetic and religious significance.

Daniel is an anonymous Old English poem based loosely on the Biblical Book of Daniel, found in the Junius Manuscript. The author and the date of Daniel are unknown. Critics have argued that Cædmon is the author of the poem, but this theory has been since disproven. Daniel, as it is preserved, is 764 lines long. There have been numerous arguments that there was originally more to this poem than survives today. The majority of scholars, however, dismiss these arguments with the evidence that the text finishes at the bottom of a page, and that there is a simple point, which translators assume indicates the end of a complete sentence. Daniel contains a plethora of lines which Old English scholars refer to as “hypermetric” or long.

Exodus is the title given to an Old English alliterative poem in the 10th century Junius manuscript. Exodus is not a paraphrase of the biblical book, but rather a re-telling of the story of the Israelites' flight from Egyptian captivity and the Crossing of the Red Sea in the manner of a "heroic epic", much like Old English poems Andreas, Judith, or even Beowulf. It is one of the densest, most allusive and complex poems in Old English, and is the focus of much critical debate.

Cædmon's Hymn is a short Old English poem attributed to Cædmon, a supposedly illiterate and unmusical cow-herder who was, according to the Northumbrian monk Bede, miraculously empowered to sing in honour of God the Creator. The poem is Cædmon's only known composition.