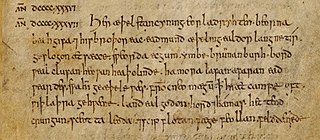

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in the course of a dream, according to the 8th-century historian Bede. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational Christian poet.

TheDream of the Rood is one of the Christian poems in the corpus of Old English literature and an example of the genre of dream poetry. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative verse. Rood is from the Old English word rōd 'pole', or more specifically 'crucifix'. Preserved in the 10th-century Vercelli Book, the poem may be as old as the 8th-century Ruthwell Cross, and is considered one of the oldest works of Old English literature.

"Deor" is an Old English poem found on folio 100r–100v of the late-10th-century collection the Exeter Book. The poem consists of a reflection on misfortune by a poet whom the poem is usually thought to name Deor. The poem has no title in the Exeter Book itself; the title has been bestowed by modern editors.

"Widsith", also known as "The Traveller's Song", is an Old English poem of 143 lines. It survives only in the Exeter Book, a manuscript of Old English poetry compiled in the late-10th century, which contains approximately one-sixth of all surviving Old English poetry. "Widsith" is located between the poems "Vainglory" and "The Fortunes of Men". Since the donation of the Exeter Book in 1076, it has been housed in Exeter Cathedral in southwestern England. The poem is for the most part a survey of the people, kings, and heroes of Europe in the Heroic Age of Northern Europe.

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has survived.

"Wulf and Eadwacer" is an Old English poem in alliterative verse of famously difficult interpretation. It has been variously characterised, (modernly) as an elegy, (historically) as a riddle, and as a song or ballad with refrain. The poem is narrated in the first person, most likely with a woman's voice. Because the audience is given so little information about her situation, some scholars argue the story was well-known, and that the unnamed speaker corresponds to named figures from other stories, for example, to Signý or that the characters Wulf and Eadwacer correspond to Theoderic the Great and his rival Odoacer. The poem's only extant text is found at folios 100v-101r in the tenth-century Exeter Book, alongside other texts to which it possesses qualitative similarities.

The Wanderer is an Old English poem preserved only in an anthology known as the Exeter Book, a manuscript dating from the late 10th century. It comprises 115 lines of alliterative verse. As is often the case with Anglo-Saxon verse, the composer and compiler are anonymous, and within the manuscript the poem is untitled.

"The Wife's Lament" or "The Wife's Complaint" is an Old English poem of 53 lines found on folio 115 of the Exeter Book and generally treated as an elegy in the manner of the German frauenlied, or "women's song". The poem has been relatively well preserved and requires few if any emendations to enable an initial reading. Thematically, the poem is primarily concerned with the evocation of the grief of the female speaker and with the representation of her state of despair. The tribulations she suffers leading to her state of lamentation, however, are cryptically described and have been subject to many interpretations. Indeed, Professor Stephen Ramsay has said, "the 'correct' interpretation of "The Wife's Lament" is one of the more hotly debated subjects in medieval studies."

"The Rhyming Poem", also written as "The Riming Poem", is a poem of 87 lines found in the Exeter Book, a tenth-century collection of Old English poetry. It is remarkable for being no later than the 10th century, in Old English, and written in rhyming couplets. Rhyme is otherwise virtually unknown among Anglo-Saxon literature, which used alliterative verse instead.

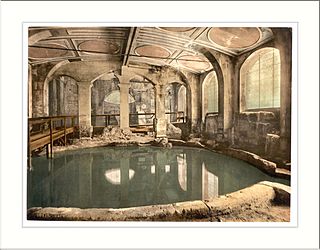

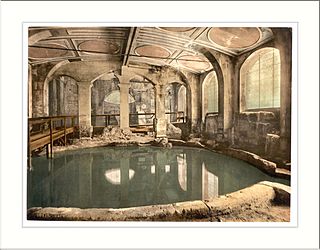

"The Ruin of the Empire", or simply "The Ruin", is an elegy in Old English, written by an unknown author probably in the 8th or 9th century, and published in the 10th century in the Exeter Book, a large collection of poems and riddles. The poem evokes the former glory of an unnamed ruined ancient city that some scholars have identified with modern Bath, juxtaposing the grand, lively past with the decaying present.

Christ I is a fragmentary collection of Old English poems on the coming of the Lord, preserved in the Exeter Book. In its present state, the poem comprises 439 lines in twelve distinct sections. In the assessment of Edward B. Irving Jr, "two masterpieces stand out of the mass of Anglo-Saxon religious poetry: The Dream of the Rood and the sequence of liturgical lyrics in the Exeter Book ... known as Christ I".

"The Husband's Message" is an anonymous Old English poem, 53 lines long and found only on folio 123 of the Exeter Book. The poem is cast as the private address of an unknown first-person speaker to a wife, challenging the reader to discover the speaker's identity and the nature of the conversation, the mystery of which is enhanced by a burn-hole at the beginning of the poem.

Ripostes of Ezra Pound is a collection of 25 poems by the American poet Ezra Pound, submitted to Swift and Co. in London in February 1912, and published by them in October that year. It was published in the United States in July 1913 by Small, Maynard and Co of Boston.

Christ III is an anonymous Old English religious poem which forms the last part of Christ, a poetic triad found at the beginning of the Exeter Book. Christ III is found on fols. 20b–32a and constitutes lines 867–1664 of Christ in Krapp and Dobbie's Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records edition. The poem is concerned with the Second Coming of Christ (parousia) and the Last Judgment.

Exodus is the title given to an Old English alliterative poem in the 10th century Junius manuscript. Exodus is not a paraphrase of the biblical book, but rather a re-telling of the story of the Israelites' flight from Egyptian captivity and the Crossing of the Red Sea in the manner of a "heroic epic", much like Old English poems Andreas, Judith, or even Beowulf. It is one of the densest, most allusive and complex poems in Old English, and is the focus of much critical debate.

The "Battle of Brunanburh" is an Old English poem. It is preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a historical record of events in Anglo-Saxon England which was kept from the late ninth to the mid-twelfth century. The poem records the Battle of Brunanburh, a battle fought in 937 between an English army and a combined army of Scots, Vikings, and Britons. The battle resulted in an English victory, celebrated by the poem in style and language like that of traditional Old English battle poetry. The poem is notable because of those traditional elements and has been praised for its authentic tone, but it is also remarkable for its fiercely nationalistic tone, which documents the development of a unified England ruled by the House of Wessex.

John D. Niles is an American scholar of medieval English literature best known for his work on Beowulf and the theory of oral literature.

The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records (ASPR) is a six-volume edition intended at the time of its publication to encompass all known Old English poetry. Despite many subsequent editions of individual poems or collections, it has remained the standard reference work for scholarship in this field.

De creatura is an 83-line Latin polystichic poem by the seventh- to eighth-century Anglo-Saxon poet Aldhelm and an important text among Anglo-Saxon riddles. The poem seeks to express the wondrous diversity of creation, usually by drawing vivid contrasts between different natural phenomena, one of which is usually physically higher and more magnificent, and one of which is usually physically lower and more mundane.