Charleston riot of 1919

The Charleston riot of 1919 started about 10 p.m. on Saturday, May 10, 1919, and ended after midnight. It began when five white sailors felt they had been cheated by a black man and, unable to find him, attacked African Americans at random. A black man named Isaac Doctor shot at them and was killed. "Within an hour, word of the street brawls and shooting got back to the Charleston Naval Yard and carloads of sailors poured into the black district."

The fighting started at a pool parlor near Beaufain Street and Charles Street (later renamed as Archdale Street) but eventually spread over much of the commercial section of King Street from Queen Street to Columbus Street. [3] There were more than 1,000 sailors, and some white civilians joined in. "Two shooting galleries in Beaufain Street were raided by the sailors, the police reported, and the small caliber rifles removed from the galleries and used by the members of the mob." They attacked black individuals, businesses, and homes. "For a time the rioters practically had possession of the downtown streets. A negro barber shop on King Street was almost wrecked and in several instances street cars were stopped by pulling down the trolley poles and negroes on the cars were beaten up. One negro was shot down as he was snatched off a car."

Admiral Frank Edmund Beatty, "who ran the Navy's southern headquarters from the Charleston Navy Yard," ordered Marines sent in, in addition to naval police ("bluejackets"). The Marines, although they were not always well disciplined themselves, worked closely with the city police force from a joint command center. The armed Marines arrived shortly after midnight. [3] By 2:30 a.m., order had been reestablished and the riot was over.

This was the worst violence in Charleston since the Civil War. Five blacks were killed, and another died later. Seventeen black men, seven white sailors, and one police officer suffered serious injuries; 35 blacks and eight sailors were admitted to hospitals. Stores had been ransacked, and black businesses and homes damaged, in some cases extensively.

Restrictions were put by the Navy on men going into Charleston, and naval troops patrolled the streets. Three sailors were court-martialed; one was acquitted and the two others, Jacob Cohen and Frank Holliday, were given a year in a naval prison, followed by dishonorable discharges. Both men had been implicated in and confessed to the murder of a black man.

"Forty-nine men, most of them white, were arraigned on charges from murder to rioting to assaulting police officers." Two black and one white man were acquitted of inciting a riot. Charges against the remainder were dropped — police were overwhelmed that night, with little time to spare for taking statements and securing evidence. 8 men received $50 ($800 in 2024) fines for carrying a concealed weapon.

Aftermath

One of Charleston's leading newspapers, The Evening Post, printed an editorial the day after the riots in which blame for the riots was placed squarely on servicemen who were not familiar with Charleston's ways. The piece included the following defense for the city:

The relations between the races in Charleston have always been of the friendliest and it is because there has been such clear definition and acceptance of them and the genuine liking for and the sense of obligation to protect the weaker race, the white people have always had.

The outbreak was a rather startling illustration of the extent to which race prejudice will go when provoked in minds uncontrolled by understanding and experience, and bring into wholesome contrast the consideration and kindness which the white people of Charleston have always shown to the respectable colored people, in whose welfare they have exhibited the most practical concern, and it emphasizes peculiarly the necessity of preserving this excellent relationship by and adherence to the line of conduct which has supported it. [3]

This uprising was one of several incidents of civil unrest that began in the so-called American Red Summer, of 1919. The Summer consisted of terrorist attacks on black communities, and white oppression in over three dozen cities and counties. In most cases, white mobs attacked African American neighborhoods. In some cases, black community groups resisted the attacks, especially in Chicago and Washington, D.C. Most deaths occurred in rural areas during events like the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas, where an estimated 100 to 240 black people and 5 white people were killed. Also occurring in 1919 were the Chicago Race Riot and Washington D.C. race riot which killed 38 and 39 people respectively, and with both having many more non-fatal injuries and extensive property damage reaching up into the millions of dollars.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

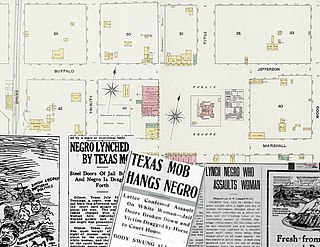

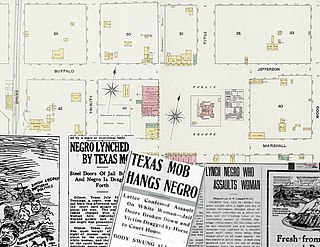

Jim McMillan was lynched in Bibb County, Alabama on June 18, 1919.

Berry Washington was a 72-year-old black man who was lynched in Milan, Georgia, in 1919. He was in jail after killing a white man who was attacking two young girls. He was taken from jail and lynched by a mob.

The Macon, Mississippi, race riot took place on June 7, 1919, in Macon, Mississippi. White members who were angry that black people were organizing to attain better work conditions beat, whipped and then forced them into exile.

The Annapolis riot of 1919 took place on June 27, 1919, between midnight and 1 AM, in Annapolis, Maryland. A mob of African-American bluejackets from the U.S. Navy fought local Annapolis African-Americans.

The Baltimore riots of 1919 were a series of riots connected to the Red Summer of 1919. As more and more African-Americans moved from the south to the industrial north they started to move into predominantly white neighborhoods. This change in the racial demographics of urban areas increased racial tension that occasionally boiled over into civil unrest.

The 1919 Norfolk race riot occurred on July 21, 1919, when a homecoming celebration for African American veterans of World War I was attacked in Norfolk, Virginia. At least two people were killed and six people were shot. City officials called in Marines and Navy personnel to restore order.

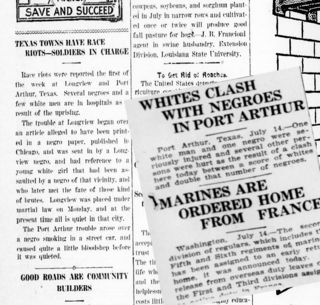

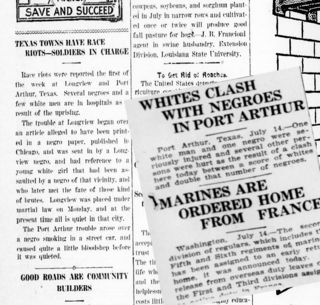

The Port Arthur riot happened on July 15, 1919, in Port Arthur, Texas. Violence started after a group of white men objected to an African American smoking near a white woman on a street car. A "score" of whites and twice that number of African Americans battled in the streets leaving two seriously injured and dozens with minor injuries.

The Putnam County, Georgia arson attack was an attack on the black community by white mobs in May of 1919.

The New London riots of 1919 were a series of racial riots between white and black Navy sailors and Marines stationed in New London and Groton, Connecticut.

The Newberry 1919 lynching attempt was the attempted lynching of Elisha Harper, Newberry, South Carolina on July 24, 1919. Harper was sent to jail for insulting a 14-year-old girl.

Newman O'Neal was the mayor of Hobson City, Alabama, until he faced death threats and was assaulted forcing him to flee.

Corbin, Kentucky race riot of 1919 was a race riot in 1919 in which a white mob forced nearly all the town's 200 black residents onto a freight train out of town, and a sundown town policy until the late 20th century.

The Wilmington, Delaware race riot of 1919 was a violent racial riot between white and black residents of Wilmington, Delaware on November 13, 1919.

Miles Phifer and Robert Crosky were lynched in Montgomery, Alabama for allegedly assaulting a white woman.

Paul Jones was lynched on November 2, 1919, after being accused of attacking a fifty-year-old white woman in Macon, Georgia.

African-American man, Jordan Jameson was lynched on November 11, 1919, in the town square of Magnolia, Columbia County, Arkansas. A large white mob seized Jameson after he allegedly shot the local sheriff. They tied him to a stake and burned him alive.

On Sunday, November 16, 1919, four African-Americans were lynched in Moberly, Missouri. Three were able to escape but one was shot to death.

Chilton Jennings was lynched on July 24, 1919, after being accused of attacking a white woman, Mrs. Virgie Haggard in Gilmer, Texas.

On December 26, 1920, an African-American man named Wade Thomas was lynched in Jonesboro, Arkansas, by a white mob. The mob seized Thomas from the Jonesboro jail after he allegedly shot local Patrolman Elmer Ragland, and murdered him.