Min dialects

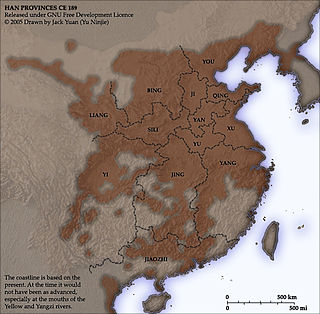

The Min homeland consists of most of the province of Fujian, and the adjacent eastern part of Guangdong. The area features rugged mountainous terrain, with short rivers that flow into the South China Sea. After the area was first settled by Chinese during the Han dynasty, most subsequent migration from north to south China passed through the valleys of the Xiang and Gan rivers to the west. Min varieties have thus developed in relative isolation. [1]

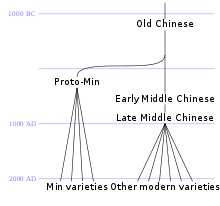

Separation from common Chinese

As described in rhyme dictionaries such as the Qieyun (601 AD), Middle Chinese initial stops and affricate consonants showed a three-way contrast between voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated and voiced consonants. There were four tones, with the fourth, the "entering tone", a checked tone comprising syllables ending in stops (-p, -t or -k).

This syllable structure was also found in neighbouring languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area – Proto-Hmong–Mien, Proto-Tai and early Vietnamese – and is largely preserved by early loans between the languages. [2] Towards the end of the first millennium AD, all of these languages experienced a tone split conditioned by initial consonants. Each tone split into an upper (yīn阴/陰) register consisting of words with voiceless initials and a lower (yáng阳/陽) register of words with voiced initials. When voicing was lost in most varieties, the register distinction became phonemic, yielding up to eight tonal categories, with a six-way contrast in unchecked syllables and a two-way contrast in checked syllables. [3]

The traditional classification of varieties of Chinese distinguished seven groups according to the reflexes of Middle Chinese voiced initials in various tonal categories. [4] For example, voiced stops are preserved in the Wu and Old Xiang groups, have merged with aspirated or unaspirated stops depending on the tone in Mandarin, and have uniformly become aspirated stops in Gan and Hakka. [5] The distinguishing characteristic of Min varieties is that voiced stops yield both aspirated and unaspirated stops in all tonal categories. Further, the distribution is consistent across Min varieties, suggesting a common ancestor in which two types of voiced stop were distinguished. [6]

Min must have diverged before two changes in other Chinese varieties (including Middle Chinese) that are not reflected in Min:

- The Old Chinese finals *-jaj and *-je merged after velar initials. This merger is reflected in a change in poetic rhyme between the Western Han (206 BC to 9 AD) and Eastern Han (25–220 AD) periods. [7]

- Old Chinese velar initials palatalized in certain environments during the Western Han period. [8] For example, Middle Chinese tsye 'branch' 支 / 枝 is believed to reflect palatalization of an Old Chinese initial *k- because other words written with the same phonetic component, such as gjeX 'skill' 伎 / 技 , have velar initials. The Proto-Min form *kiA 'branch' retains the original initial. [9]

However, the palatalization of dental stop initials, which had occurred in some dialects by the Eastern Han period, is common to Middle Chinese and Min. [10] Baxter and Sagart suggest that the later part of the Proto-Min period may have overlapped with Early Middle Chinese. [11]

Pointing to features of Min varieties that are also found in Hakka and Yue varieties, Jerry Norman suggests that the three groups are descended from a variety spoken in the lower Yangtze region during the Han period, which he calls Old Southern Chinese. [12] He argues that this dialect belonged to the group of dialects known as Wu (吳) or Jiangdong (江東) in the Western Jin period, when the writer Guo Pu (early 4th century AD) described them as quite distinct from other Chinese varieties. [13] Some of the distinctive Jiangdong words mentioned by Guo Pu appear to be preserved in modern Min varieties, including Proto-Min *giA 'leech' and *lhɑnC 'young fowl'. [14] This language entered Fujian after the area was opened to Chinese settlement by the defeat of the Minyue state by the armies of Emperor Wu of Han in 110 BC. [15] Norman argues that Hakka and Yue have resulted from overlays of this language by successive waves of influence from northern China. [16]

When Chinese soldiers and settlers moved south from their homeland in the North China Plain, they came into contact with speakers of Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic languages. Early loans from Chinese into these languages date from around Han times and thus contain evidence of the sounds of Chinese as spoken in the south at that time. [17]

Strata

Norman identifies four main layers in the vocabulary of modern Min varieties:

- A non-Chinese substratum from the original languages of Minyue, which Norman believes were Austroasiatic. [18] These etymologies have been disputed by Laurent Sagart, and there is no other evidence for an early Austroasiatic presence in southeast China. [19]

- The earliest Chinese layer, brought to Fujian by settlers from Zhejiang to the north during the Han dynasty [13] (compare Eastern Han Chinese).

- A layer from the Northern and Southern dynasties period, largely consistent with the phonology of the Qieyun dictionary, which was published in 601 AD but based on earlier dictionaries that are now lost [20] (Early Middle Chinese).

- A literary layer based on the koiné of Chang'an, the capital of the Tang dynasty [21] (Late Middle Chinese).

Since the latter two layers can largely be derived from the Qieyun, Norman sought to focus on the earlier layers. [20]

Subgroups

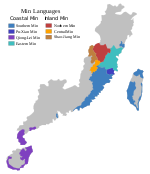

Early classifications, such as those of Li Fang-Kuei in 1937 and Yuan Jiahua in 1960, divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups. [22] [23] However, in a 1963 report on a survey of Fujian, Pan Maoding and colleagues argued that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups. [24] The inland varieties are distinguished by consistently having two distinct reflexes of Middle Chinese /l/. [23] The two groups also have differences in their vocabulary, including their pronoun systems. [25]

The coastal dialects are divided into three subgroups: [26]

- Eastern Min

- including Fuzhou, Ningde and Fu'an in northeast Fujian

- Pu-Xian Min

- including Putian and Xianyou on the central Fujian coast

- Southern Min

- including Xiamen, Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in southern Fujian, and Chaozhou, Jieyang and Shantou in eastern Guangdong

They divided the inland dialects into two subgroups:

- Northern Min

- including Jianyang, Jian'ou, Chong'an, Zhenghe and Shibei

- Central Min

- including Sanming and Yong'an in western Fujian

Several varieties in the far west of Fujian include features of Min and the neighbouring Gan and Hakka groups, making them difficult to classify. In the Shaojiang dialects, spoken in the northwestern Fujian counties of Shaowu and Jiangle, the reflexes of Middle Chinese voiced stops are uniformly aspirated, as in Gan and Hakka, leading some workers to assign them to one of these groups. Pan et al. described them as intermediate between Min and Hakka. [27] However, Norman showed that their tonal development could only be explained in terms of the same two classes of voiced initial assumed for Min dialects. He suggested that they were inland Min dialects that had been subject to heavy Gan or Hakka influence. [28] Norman's student David Prager Branner argued that the varieties of Longyan and the township of Wan'an, in the southwestern part of the province, were coastal Min varieties, but outside of the three subgroups identified by Pan. [29] [30]