Mandarin is a group of Chinese language dialects that are natively spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of the phonology of Standard Chinese, the official language of China. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese. Many varieties of Mandarin, such as those of the Southwest and the Lower Yangtze, are not mutually intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin as a group is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers.

Yue is a branch of the Sinitic languages primarily spoken in Southern China, particularly in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi.

Middle Chinese or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the Qieyun, a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren believed that the dictionary recorded a speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties. However, based on the preface of the Qieyun, most scholars now believe that it records a compromise between northern and southern reading and poetic traditions from the late Northern and Southern dynasties period. This composite system contains important information for the reconstruction of the preceding system of Old Chinese phonology.

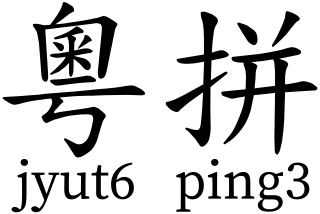

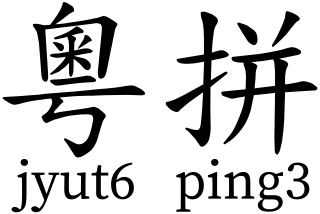

The Linguistic Society of Hong Kong Cantonese Romanization Scheme, also known as Jyutping, is a romanisation system for Cantonese developed in 1993 by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong (LSHK).

In linguistics, a consonant cluster, consonant sequence or consonant compound, is a group of consonants which have no intervening vowel. In English, for example, the groups and are consonant clusters in the word splits. In the education field it is variously called a consonant cluster or a consonant blend.

Taishanese, alternatively romanized in Cantonese as Toishanese or Toisanese, in local dialect as Hoisanese or Hoisan-wa, is a Yue Chinese dialect native to Taishan, Guangdong. Although related, Taishanese has little mutual intelligibility with Cantonese. Taishanese is also spoken throughout Sze Yup, located on the western fringe of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong China. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, most of the Chinese emigration to North America originated from Sze Yup. Thus, up to the mid-20th century, Taishanese was the dominant variety of the Chinese language spoken in Chinatowns in Canada and the United States. It was formerly the lingua franca of the overseas Chinese residing in the United States.

Postalveolar or post-alveolar consonants are consonants articulated with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge. Articulation is farther back in the mouth than the alveolar consonants, which are at the ridge itself, but not as far back as the hard palate, the place of articulation for palatal consonants. Examples of postalveolar consonants are the English palato-alveolar consonants, as in the words "ship", "'chill", "vision", and "jump", respectively.

Historical Chinese phonology deals with reconstructing the sounds of Chinese from the past. As Chinese is written with logographic characters, not alphabetic or syllabary, the methods employed in Historical Chinese phonology differ considerably from those employed in, for example, Indo-European linguistics; reconstruction is more difficult because, unlike Indo-European languages, no phonetic spellings were used.

In phonetics, alveolo-palatal consonants, sometimes synonymous with pre-palatal consonants, are intermediate in articulation between the coronal and dorsal consonants, or which have simultaneous alveolar and palatal articulation. In the official IPA chart, alveolo-palatals would appear between the retroflex and palatal consonants but for "lack of space". Ladefoged and Maddieson characterize the alveolo-palatals as palatalized postalveolars, articulated with the blade of the tongue behind the alveolar ridge and the body of the tongue raised toward the palate, whereas Esling describes them as advanced palatals (pre-palatals), the furthest front of the dorsal consonants, articulated with the body of the tongue approaching the alveolar ridge. These descriptions are essentially equivalent, since the contact includes both the blade and body of the tongue. They are front enough that the fricatives and affricates are sibilants, the only sibilants among the dorsal consonants.

The Hong Kong Government uses an unpublished system of Romanisation of Cantonese for public purposes which is based on the 1888 standard described by Roy T Cowles in 1914 as Standard Romanisation. The primary need for Romanisation of Cantonese by the Hong Kong Government is in the assigning of names to new streets and places. It has not formally or publicly disclosed its method for determining the appropriate Romanisation in any given instance.

Guangdong Romanization refers to the four romanization schemes published by the Guangdong Provincial Education Department in 1960 for transliterating Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka and Hainanese. The schemes utilized similar elements with some differences in order to adapt to their respective spoken varieties.

Starting in the 1980s, proper Cantonese pronunciation has been much promoted in Hong Kong, with the scholar Richard Ho (何文匯) as its iconic campaigner. The very idea of proper pronunciation of Cantonese is controversial, since the concept of labeling native speakers' usage and speech in terms of correctness is not generally supported by linguistics. Law et al. (2001) point out that the phrase 懶音 laan5 jam1 "lazy sounds," most commonly discussed in relation to phonetic changes in Hong Kong Cantonese, implies that the speaker is unwilling to put forth sufficient effort to articulate the standard pronunciation.

General Chinese is a diaphonemic orthography invented by Yuen Ren Chao to represent the pronunciations of all major varieties of Chinese simultaneously. It is "the most complete genuine Chinese diasystem yet published". It can also be used for the Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese pronunciations of Chinese characters, and challenges the claim that Chinese characters are required for interdialectal communication in written Chinese.

Wong Shik Ling published a scheme of phonetic symbols for Cantonese based on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in the book A Chinese Syllabary Pronounced According to the Dialect of Canton. The scheme has been widely used in Chinese dictionaries published in Hong Kong. The scheme, known as S. L. Wong system (黃錫凌式), is a broad phonemic transcription system based on IPA and its analysis of Cantonese phonemes is grounded in the theories of Y. R. Chao.

A checked tone, commonly known by the Chinese calque entering tone, is one of the four syllable types in the phonology of Middle Chinese. Although usually translated as "tone", a checked tone is not a tone in the phonetic sense but rather a syllable that ends in a stop consonant or a glottal stop. Separating the checked tone allows -p, -t, and -k to be treated as allophones of -m, -n, and -ng, respectively, since they are in complementary distribution. Stops appear only in the checked tone, and nasals appear only in the other tones. Because of the origin of tone in Chinese, the number of tones found in such syllables is smaller than the number of tones in other syllables. Chinese phonetics have traditionally counted them separately.

Hong Kong Cantonese is a dialect of the Cantonese language of the Sino-Tibetan family.

The Yale romanization of Cantonese was developed by Gerard P. Kok for his and Parker Po-fei Huang's textbook Speak Cantonese initially circulated in looseleaf form in 1952 but later published in 1958. Unlike the Yale romanization of Mandarin, it is still widely used in books and dictionaries, especially for foreign learners of Cantonese. It shares some similarities with Hanyu Pinyin in that unvoiced, unaspirated consonants are represented by letters traditionally used in English and most other European languages to represent voiced sounds. For example, is represented as b in Yale, whereas its aspirated counterpart, is represented as p. Students attending The Chinese University of Hong Kong's New-Asia Yale-in-China Chinese Language Center are taught using Yale romanization.

The phonology of Standard Chinese has historically derived from the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. However, pronunciation varies widely among speakers, who may introduce elements of their local varieties. Television and radio announcers are chosen for their ability to affect a standard accent. Elements of the sound system include not only the segments—e.g. vowels and consonants—of the language, but also the tones applied to each syllable. In addition to its four main tones, Standard Chinese has a neutral tone that appears on weak syllables.

In Middle Chinese, the phonological system of medieval rime dictionaries and rime tables, the final is the rest of the syllable after the initial consonant. This analysis is derived from the traditional Chinese fanqie system of indicating pronunciation with a pair of characters indicating the sounds of the initial and final parts of the syllable respectively, though in both cases several characters were used for each sound. Reconstruction of the pronunciation of finals is much more difficult than for initials due to the combination of multiple phonemes into a single class, and there is no agreement as to their values. Because of this lack of consensus, understanding of the reconstruction of finals requires delving into the details of rime tables and rime dictionaries.

ISO 11940-2 is an ISO standard for a simplified transcription of the Thai language into Latin characters.