In phonetics, aspiration is the strong burst of breath that accompanies either the release or, in the case of preaspiration, the closure of some obstruents. In English, aspirated consonants are allophones in complementary distribution with their unaspirated counterparts, but in some other languages, notably most South Asian languages and East Asian languages, the difference is contrastive.

In phonetics, palatalization or palatization is a way of pronouncing a consonant in which part of the tongue is moved close to the hard palate. Consonants pronounced this way are said to be palatalized and are transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet by affixing the letter ⟨ʲ⟩ to the base consonant. Palatalization cannot minimally distinguish words in most dialects of English, but it may do so in languages such as Russian, Japanese, Norwegian, Võro, Irish and Kashmiri.

In linguistics, lenition is a sound change that alters consonants, making them more sonorous. The word lenition itself means "softening" or "weakening". Lenition can happen both synchronically and diachronically. Lenition can involve such changes as voicing a voiceless consonant, causing a consonant to relax occlusion, to lose its place of articulation, or even causing a consonant to disappear entirely.

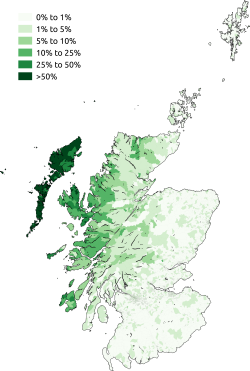

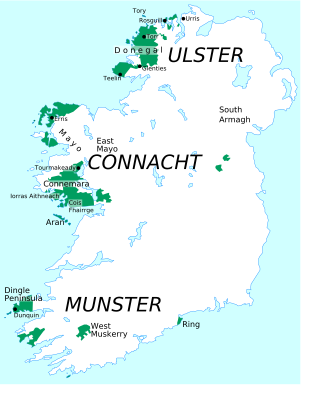

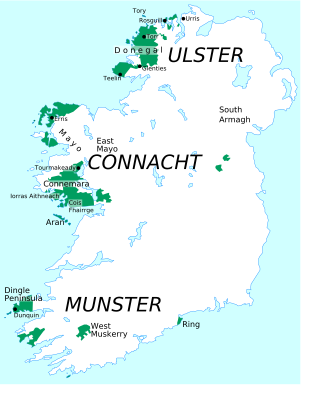

Irish phonology varies from dialect to dialect; there is no standard pronunciation of Irish. Therefore, this article focuses on phenomena shared by most or all dialects, and on the major differences among the dialects. Detailed discussion of the dialects can be found in the specific articles: Ulster Irish, Connacht Irish, and Munster Irish.

In phonetics, nasalization is the production of a sound while the velum is lowered, so that some air escapes through the nose during the production of the sound by the mouth. Examples of archetypal nasal sounds include and.

Marshallese, also known as Ebon, is a Micronesian language spoken in the Marshall Islands. The language of the Marshallese people, it is spoken by nearly all of the country's population of 59,000, making it the principal language. There are also roughly 27,000 Marshallese citizens residing in the United States, nearly all of whom speak Marshallese, as well as residents in other countries such as Nauru and Kiribati.

The phonology of Catalan, a Romance language, has a certain degree of dialectal variation. Although there are two standard varieties, one based on Central Eastern dialect and another one based on South-Western or Valencian dialect, this article deals with features of all or most dialects, as well as regional pronunciation differences.

Irish orthography is the set of conventions used to write Irish. A spelling reform in the mid-20th century led to An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, the modern standard written form used by the Government of Ireland, which regulates both spelling and grammar. The reform removed inter-dialectal silent letters, simplified some letter sequences, and modernised archaic spellings to reflect modern pronunciation, but it also removed letters pronounced in some dialects but not in others.

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic, is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from c. 600 to c. 900. The main contemporary texts are dated c. 700–850; by 900 the language had already transitioned into early Middle Irish. Some Old Irish texts date from the 10th century, although these are presumably copies of texts written at an earlier time. Old Irish is thus forebear to Modern Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

Irish, like all modern Celtic languages, is characterized by its initial consonant mutations. These mutations affect the initial consonant of a word under specific morphological and syntactic conditions. The mutations are an important tool in understanding the relationship between two words and can differentiate various meanings.

Swedish has a large vowel inventory, with nine vowels distinguished in quality and to some degree in quantity, making 18 vowel phonemes in most dialects. Another notable feature is the pitch accent, a development which it shares with Norwegian. Swedish pronunciation of most consonants is similar to that of other Germanic languages.

The phonology of Japanese features a phonemic inventory of five vowels and 14 or more consonants. The phonotactics are relatively simple, allowing for few consonant clusters. Japanese phonology has been affected by the presence of several layers of vocabulary in the language: in addition to native Japanese vocabulary, Japanese has a large amount of Chinese-based vocabulary and loanwords from other languages.

Wong Shik Ling published a scheme of phonetic symbols for Cantonese based on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in the book A Chinese Syllabary Pronounced According to the Dialect of Canton. The scheme has been widely used in Chinese dictionaries published in Hong Kong. The scheme, known as S. L. Wong system (黃錫凌式), is a broad phonemic transcription system based on IPA and its analysis of Cantonese phonemes is grounded in the theories of Y. R. Chao.

In articulatory phonetics, fortition, also known as strengthening, is a consonantal change that increases the degree of stricture. It is the opposite of the more common lenition. For example, a fricative or an approximant may become a stop. Although not as typical of sound change as lenition, fortition may occur in prominent positions, such as at the beginning of a word or stressed syllable; as an effect of reducing markedness; or due to morphological leveling.

The phonological system of the Hawaiian language is based on documentation from those who developed the Hawaiian alphabet during the 1820s as well as scholarly research conducted by lexicographers and linguists from 1949 to present.

This article deals with the phonology and phonetics of Standard Modern Greek. For phonological characteristics of other varieties, see varieties of Modern Greek, and for Cypriot, specifically, see Cypriot Greek § Phonology.

In phonetics, preaspiration is a period of voicelessness or aspiration preceding the closure of a voiceless obstruent, basically equivalent to an -like sound preceding the obstruent. In other words, when an obstruent is preaspirated, the glottis is opened for some time before the obstruent closure. To mark preaspiration using the International Phonetic Alphabet, the diacritic for regular aspiration, ⟨ʰ⟩, can be placed before the preaspirated consonant. However, Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:70) prefer to use a simple cluster notation, e.g. ⟨hk⟩ instead of ⟨ʰk⟩.

This article explains the phonology of Malay and Indonesian based on the pronunciation of Standard Malay, which is the official language of Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia, and Indonesian, which is the official language of Indonesia and a working language in Timor Leste. There are two main standards for Malay pronunciation, the Johor-Riau standard, used in Brunei and Malaysia, and the Baku, used in Indonesia and Singapore.

Ingrian is a nearly extinct Finnic language of Russia. The spoken language remains unstandardised, and as such statements below are about the four known dialects of Ingrian and in particular the two extant dialects.

Old Irish was affected by a series of phonological changes that radically altered its appearance compared with Proto-Celtic and older Celtic languages. The changes occurred at a fairly rapid pace between 350 and 550 CE.