Related Research Articles

The close-mid central rounded vowel, or high-mid central rounded vowel, is a type of vowel sound. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ɵ⟩, a lowercase barred letter o.

The sound system of Norwegian resembles that of Swedish. There is considerable variation among the dialects, and all pronunciations are considered by official policy to be equally correct – there is no official spoken standard, although it can be said that Eastern Norwegian Bokmål speech has an unofficial spoken standard, called Urban East Norwegian or Standard East Norwegian, loosely based on the speech of the literate classes of the Oslo area. This variant is the most common one taught to foreign students.

Bernese German, like other High Alemannic varieties, has a two-way contrast in plosives and fricatives that is not based on voicing, but on length. The absence of voice in plosives and fricatives is typical for all High German varieties, but many of them have no two-way contrast due to general lenition.

The phonology of the Persian language varies between regional dialects, standard varieties, and even from older variates of Persian. Persian is a pluricentric language and countries that have Persian as an official language have separate standard varieties, namely: Standard Dari (Afghanistan), Standard Iranian Persian and Standard Tajik (Tajikistan). The most significant differences between standard varieties of Persian are their vowel systems. Standard varieties of Persian have anywhere from 6 to 8 vowel distinctions, and similar vowels may be pronounced differently between standards. However, there are not many notable differences when comparing consonants, as all standard varieties a similar amount of consonant sounds. Though, colloquial varieties generally have more differences than their standard counterparts. Most dialects feature contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters.

Old English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative since Old English is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large corpus of the language, and the orthography apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully, so it is not difficult to draw certain conclusions about the nature of Old English phonology.

Dutch phonology is similar to that of other West Germanic languages, especially Afrikaans and West Frisian.

The Greek language underwent pronunciation changes during the Koine Greek period, from about 300 BC to 400 AD. At the beginning of the period, the pronunciation was close to Classical Greek, while at the end it was almost identical to Modern Greek.

Unlike many languages, Icelandic has only very minor dialectal differences in sounds. The language has both monophthongs and diphthongs, and many consonants can be voiced or unvoiced.

Hindustani is the lingua franca of northern India and Pakistan, and through its two standardized registers, Hindi and Urdu, a co-official language of India and co-official and national language of Pakistan respectively. Phonological differences between the two standards are minimal.

Hard and soft G in Dutch refers to a phonetic phenomenon of the pronunciation of the letters ⟨g⟩ and ⟨ch⟩ and also a major isogloss within that language.

Lithuanian has eleven vowels and 45 consonants, including 22 pairs of consonants distinguished by the presence or absence of palatalization. Most vowels come in pairs which are differentiated through length and degree of centralization.

Afenmai (Afemai), Yekhee, or Iyekhe, is an Edoid language spoken in Edo State, Nigeria by Afenmai people. Not all speakers recognize the name Yekhee; some use the district name Etsako.

This article aims to describe the phonology and phonetics of central Luxembourgish, which is regarded as the emerging standard.

The phonology of Old Saxon mirrors that of the other ancient Germanic languages, and also, to a lesser extent, that of modern West Germanic languages such as English, Dutch, Frisian, German, and Low German.

The phonological system of the Old English language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included a number of vowel shifts, and the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions.

This article covers the phonology of the Orsmaal-Gussenhoven dialect, a variety of Getelands spoken in Orsmaal-Gussenhoven, a village in the Linter municipality.

Weert dialect or Weert Limburgish is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Dutch city of Weert alongside Standard Dutch. All of its speakers are bilingual with standard Dutch. There are two varieties of the dialect: rural and urban. The latter is called Stadsweerts in Standard Dutch and Stadswieërts in the city dialect. Van der Looij gives the Dutch name buitenijen for the peripheral dialect.

This article covers the phonology of the Kerkrade dialect, a West Ripuarian language variety spoken in parts of the Kerkrade municipality in the Netherlands and Herzogenrath in Germany.

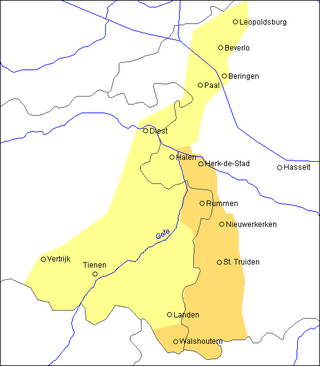

Getelands or West Getelands is a South Brabantian dialect spoken in the eastern part of Flemish Brabant as well as the western part of Limburg in Belgium. It is a transitional dialect between South Brabantian and West Limburgish.

The phonology of the Maastrichtian dialect, especially with regards to vowels is quite extensive due to the dialect's tonal nature.

References

- ↑ Based on the consonant table in Sipma (1913 :8). The allophones [ɲ,ɡ,β̞] are not included.

- ↑ Hoekstra (2001), p. 84.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), pp. 8, 15–16.

- 1 2 Keil (2003), p. 8.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), p. 29.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (1982), p. 6.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), pp. 8, 15–17.

- ↑ Collins & Mees (1982), p. 7.

- ↑ Gussenhoven (1999), p. 74.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), p. 15.

- ↑ Keil (2003), p. 7.

- 1 2 Hoekstra (2001), p. 86.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), pp. 15, 17.

- 1 2 Sipma (1913), p. 36.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Booij (1989), p. 319.

- ↑ Hoekstra & Tiersma (2013), p. 509.

- 1 2 3 Visser (1997), p. 14.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), p. 9.

- ↑ Visser (1997), p. 24.

- ↑ Visser (1997), p. 19.

- 1 2 3 van der Veen (2001), p. 102.

- ↑ Sipma (1913), pp. 6, 8, 10.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), p. 11.

- 1 2 For instance Booij (1989), Tiersma (1999), van der Veen (2001), Keil (2003) and Hoekstra & Tiersma (2013).

- ↑ ⟨ɵ⟩ is used by Sipma (1913) (as ⟨ö⟩, which is how it was transcribed in 1913' see History of the International Phonetic Alphabet), and ⟨ʏ⟩ is used by de Haan (2010).

- ↑ Visser (1997), pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Visser (1997), p. 17.

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), p. 10.

- ↑ Visser (1997), p. 23.

- 1 2 Hoekstra (2001), p. 83.

- 1 2 3 de Haan (2010), p. 333.

- ↑ Hoekstra (2003 :202), citing Hof (1933 :14)

- 1 2 3 Tiersma (1999), p. 12.

- ↑ For instance, Tiersma (1999), Keil (2003) and Hoekstra & Tiersma (2013).

- ↑ For instance, Booij (1989), Hoekstra (2001) and Keil (2003).

- ↑ For instance, Tiersma (1999) and Hoekstra & Tiersma (2013).

- ↑ Tiersma (1999), pp. 12, 36.

- ↑ Booij (1989), pp. 319–320.

- ↑ Hoekstra & Tiersma (2013), pp. 509–510.

- ↑ "Taalportaal | Constraints on sequences of three or four vowels".