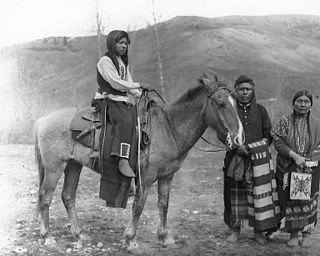

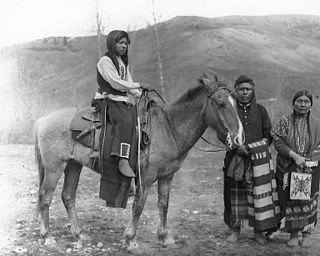

The Nez Perce are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region has been occupied for at least 11,500 years.

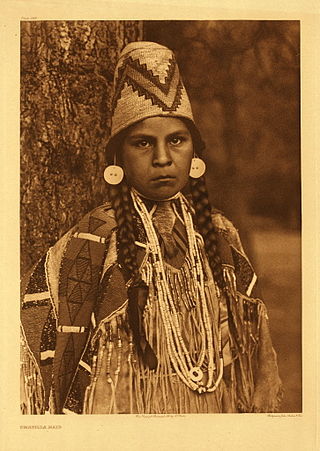

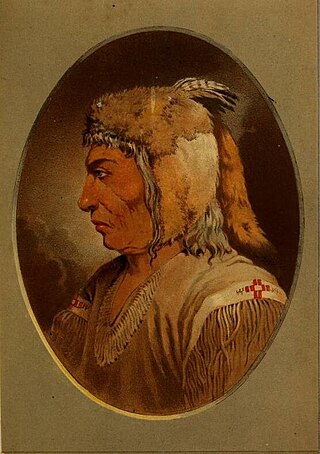

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Walla Walla, Walawalałáma, sometimes Walúulapam, are a Sahaptin Indigenous people of the Northwest Plateau. The duplication in their name expresses the diminutive form. The name Walla Walla is translated several ways but most often as "many waters".

The Cayuse are a Native American tribe in what is now the state of Oregon in the United States. The Cayuse tribe shares a reservation and government in northeastern Oregon with the Umatilla and the Walla Walla tribes as part of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The reservation is located near Pendleton, Oregon, at the base of the Blue Mountains.

The Palouse are a Sahaptin tribe recognized in the Treaty of 1855 with the United States along with the Yakama. It was negotiated at the 1855 Walla Walla Council. A variant spelling is Palus. Today they are enrolled in the federally recognized Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and some are also represented by the Colville Confederated Tribes, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Nez Perce Tribe.

Sahaptian is a two-language branch of the Plateau Penutian family spoken by Native American peoples in the Columbia Plateau region of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho in the northwestern United States.

The Umatilla are a Sahaptin-speaking Native American tribe who traditionally inhabited the Columbia Plateau region of the northwestern United States, along the Umatilla and Columbia rivers.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation are the federally recognized confederations of three Sahaptin-speaking Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited the Columbia River Plateau region: the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla.

Celilo Falls was a tribal fishing area on the Columbia River, just east of the Cascade Mountains, on what is today the border between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington. The name refers to a series of cascades and waterfalls on the river, as well as to the native settlements and trading villages that existed there in various configurations for 15,000 years. Celilo was the oldest continuously inhabited community on the North American continent until 1957, when the falls and nearby settlements were submerged by the construction of The Dalles Dam. In 2019, there were calls by tribal leaders to restore the falls.

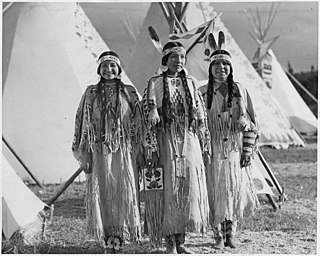

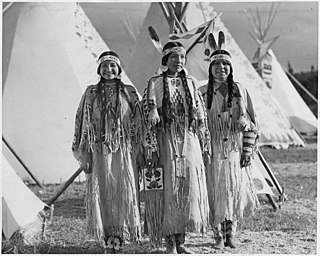

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau, also referred to by the phrase Indigenous peoples of the Plateau, and historically called the Plateau Indians are Indigenous peoples of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada, and the non-coastal regions of the Northwestern United States.

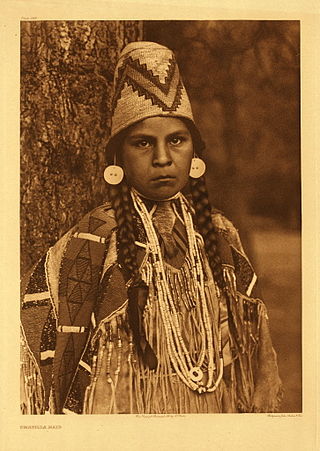

Nez Perce, also spelled Nez Percé or called nimipuutímt, is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin. Nez Perce comes from the French phrase nez percé, "pierced nose"; however, Nez Perce, who call themselves nimiipuu, meaning "the people", did not pierce their noses. This misnomer may have occurred as a result of confusion on the part of the French, as it was surrounding tribes who did so.

The Sahaptin are a number of Native American tribes who speak dialects of the Sahaptin language. The Sahaptin tribes inhabited territory along the Columbia River and its tributaries in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Sahaptin-speaking peoples included the Klickitat, Kittitas, Yakama, Wanapum, Palus, Lower Snake, Skinpah, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, and Nez Perce.

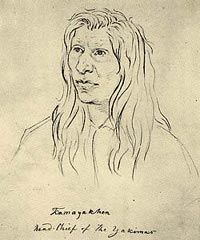

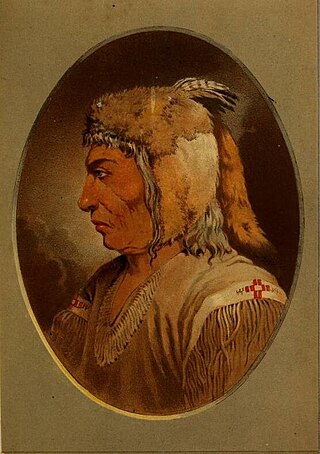

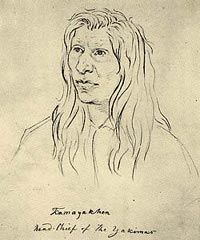

Kamiakin (1800–1877) (Yakama) was a leader of the Yakama, Palouse, and Klickitat peoples east of the Cascade Mountains in what is now southeastern Washington state. In 1855, he was disturbed by threats of the Territorial Governor, Isaac Stevens, against the tribes of the Columbia Plateau. After being forced to sign a treaty of land cessions, Kamiakin organized alliances with 14 other tribes and leaders, and led the Yakima War of 1855–1858.

Wasco-Wishram are two closely related Chinook Indian tribes from the Columbia River in Oregon. Today the tribes are part of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs living in the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Oregon and Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation living in the Yakama Indian Reservation in Washington.

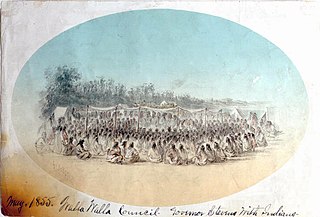

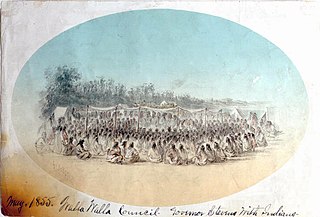

The Walla Walla Council (1855) was a meeting in the Pacific Northwest between the United States and sovereign tribal nations of the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama. The council occurred on May 29 – June 11; the treaties signed at this council on June 9 were ratified by the U.S. Senate four years later in 1859.

Umatilla is a variety of Southern Sahaptin, part of the Sahaptian subfamily of the Plateau Penutian group. It was spoken during late aboriginal times along the Columbia River and is therefore also called Columbia River Sahaptin. It is currently spoken as a first language by a few dozen elders and some adults in the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon. Some sources say that Umatilla is derived from imatilám-hlama: hlama means 'those living at' or 'people of' and there is an ongoing debate about the meaning of imatilám, but it is said to be an island in the Columbia River. B. Rigsby and N. Rude mention the village of ímatalam that was situated at the mouth of the Umatilla River and where the language was spoken.

Bruce Rigsby was an American-Australian anthropologist specializing in the languages and ethnography of native peoples on both continents. He was professor emeritus at Queensland University, and a member of both the Australian Anthropological Society and the American Anthropological Association.

The Yakima practical alphabet is an orthography used to write Sahaptin languages of the Pacific Northwest of North America.

Virginia R. Beavert was a Native American linguist of the Ichishkíin language at the University of Oregon.

The Skinpah were a Sahaptin-speaking people of the Tenino dialect living along the northern bank of the Columbia River in what is now south-central Washington. They were first recorded as the E-nee-shers in 1805 by Lewis and Clark. Their village, Sk'in, was located adjacent to Celilo Falls in modern day Klickitat County.