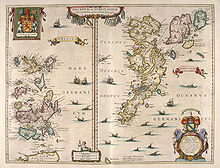

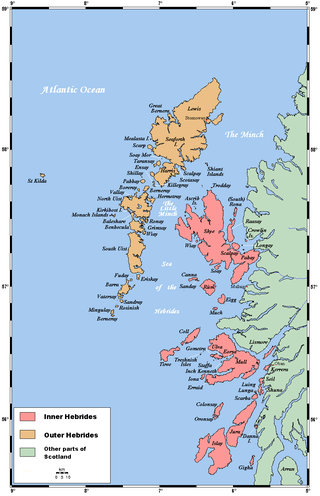

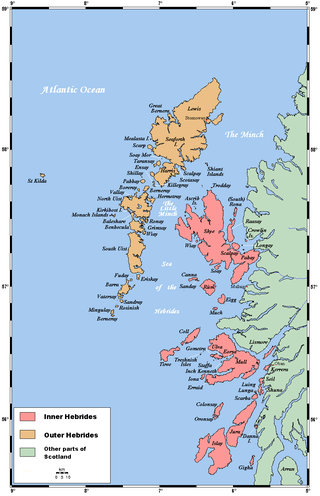

The Hebrides are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrides.

The Picts were a group of peoples in northern Britain, north of the Firth of Forth, in the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pictish stones. The name Picti appears in written records as an exonym from the late third century AD. They are assumed to have been descendants of the Caledonii and other northern Iron Age tribes. Their territory is referred to as "Pictland" by modern historians. Initially made up of several chiefdoms, it came to be dominated by the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the seventh century. During this Verturian hegemony, Picti was adopted as an endonym. This lasted around 160 years until the Pictish kingdom merged with that of Dál Riata to form the Kingdom of Alba, ruled by the House of Alpin. The concept of "Pictish kingship" continued for a few decades until it was abandoned during the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda.

The Outer Hebrides or Western Isles, sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland. The islands are geographically coextensive with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland. They form part of the archipelago of the Hebrides, separated from the Scottish mainland and from the Inner Hebrides by the waters of the Minch, the Little Minch, and the Sea of the Hebrides.

Dál Riata or Dál Riada was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is now Argyll in Scotland and part of County Antrim in Northern Ireland. After a period of expansion, Dál Riata eventually became associated with the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba.

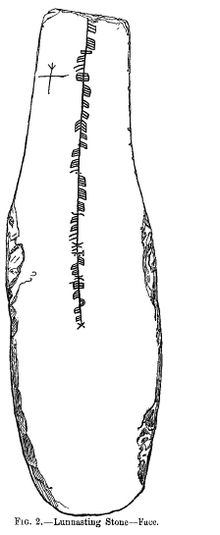

Pictish is an extinct Brittonic Celtic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographical and personal names found on monuments and early medieval records in the area controlled by the kingdoms of the Picts. Such evidence, however, shows the language to be an Insular Celtic language related to the Brittonic language then spoken in most of the rest of Britain.

Fetlar is one of the North Isles of Shetland, Scotland, with a usually resident population of 61 at the time of the 2011 census. Its main settlement is Houbie on the south coast, home to the Fetlar Interpretive Centre. Other settlements include Aith, Funzie, Herra and Tresta. Fetlar is the fourth-largest island of Shetland and has an area of just over 4,000 ha.

The Northern Isles are a chain of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The climate is cool and temperate and highly influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main island groups: Shetland and Orkney. There are a total of 36 inhabited islands, with the fertile agricultural islands of Orkney contrasting with the more rugged Shetland islands to the north, where the economy is more dependent on fishing and the oil wealth of the surrounding seas. Both archipelagos have a developing renewable energy industry. They share a common Pictish and Norse history, and were part of the Kingdom of Norway before being absorbed into the Kingdom of Scotland in the 15th century. The islands played a significant naval role during the world wars of the 20th century.

The Papar were, according to early Icelandic sagas, Irish monks who took eremitic residence in parts of what is now Iceland before that island's habitation by the Norsemen of Scandinavia, as evidenced by the sagas and recent archaeological findings.

The Earldom of Orkney was a Norse territory ruled by the earls of Orkney from the ninth century until 1472. It was founded during the Viking Age by Viking raiders and settlers from Scandinavia. In the ninth and tenth centuries it covered the Northern Isles (Norðreyjar) of Orkney and Shetland, as well as Caithness and Sutherland on the mainland. It was a dependent territory of the Kingdom of Norway until 1472, when it was absorbed into the Kingdom of Scotland. Originally, the title of Jarl or Earl of Orkney was heritable.

Fortriu was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and Easter Ross area. Fortriu is a term used by historians as it is not known what name its people used to refer to their polity. Historians also sometimes use the name synonymously with Pictland in general.

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Cait or Cat was a Pictish kingdom originating c. AD 800 during the Early Middle Ages. It was centered in what is now Caithness in northern Scotland. It was, according to Pictish legend, founded by Caitt, one of the seven sons of the ancestor figure Cruithne. The territory of Cait covered not only modern Caithness, but also southeast Sutherland.

The languages of Scotland belong predominantly to the Germanic and Celtic language families. The classification of the Pictish language was once controversial, but it is now generally considered a Celtic language. Today, the main language spoken in Scotland is English, while Scots and Scottish Gaelic are minority languages. The dialect of English spoken in Scotland is referred to as Scottish English.

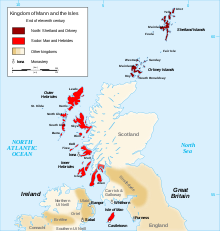

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the early Middle Ages, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 AD and the rise of the kingdom of Alba in 900 AD. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

Hinba is an island in Scotland of uncertain location that was the site of a small monastery associated with the Columban church on Iona. Although a number of details are known about the monastery and its early superiors, and various anecdotes dating from the time of Columba of a mystical nature have survived, modern scholars are divided as to its whereabouts. The source of information about the island is Adomnán's late 7th-century Vita Columbae.

Scandinavian Scotland was the period from the 8th to the 15th centuries during which Vikings and Norse settlers, mainly Norwegians and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, and their descendants colonised parts of what is now the periphery of modern Scotland. Viking influence in the area commenced in the late 8th century, and hostility between the Scandinavian earls of Orkney and the emerging thalassocracy of the Kingdom of the Isles, the rulers of Ireland, Dál Riata and Alba, and intervention by the crown of Norway were recurring themes.

The geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages covers all aspects of the land that is now Scotland, including physical and human, between the departure of the Romans in the early fifth century from what are now the southern borders of the country, to the adoption of the major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Scotland was defined by its physical geography, with its long coastline of inlets, islands and inland lochs, high proportion of land over 60 metres above sea level and heavy rainfall. It is divided between the Highlands and Islands and Lowland regions, which were subdivided by geological features including fault lines, mountains, hills, bogs and marshes. This made communications by land problematic and raised difficulties for political unification, but also for invading armies.

The Christianisation of Scotland was the process by which Christianity spread in what is now Scotland, which took place principally between the fifth and tenth centuries.

Scottish literature in the Middle Ages is literature written in Scotland, or by Scottish writers, between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century, until the establishment of the Renaissance in the late fifteenth century and early sixteenth century. It includes literature written in Brythonic, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French and Latin.