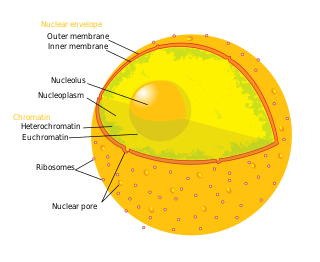

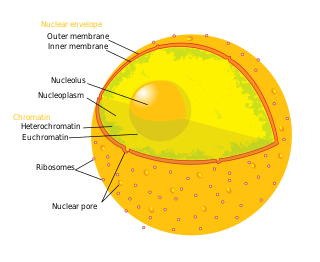

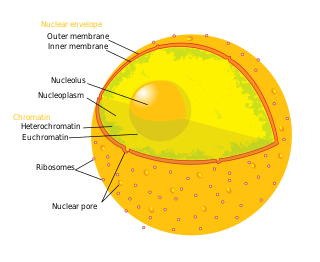

The cell nucleus is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have no nuclei, and a few others including osteoclasts have many. The main structures making up the nucleus are the nuclear envelope, a double membrane that encloses the entire organelle and isolates its contents from the cellular cytoplasm; and the nuclear matrix, a network within the nucleus that adds mechanical support.

Progeria is a specific type of progeroid syndrome, also known as Hutchinson–Gilford syndrome or Hutchinson–Gilford progeroid syndrome (HGPS). A single gene mutation is responsible for causing progeria. The gene, known as lamin A (LMNA), makes a protein necessary for holding the nucleus of the cell together. When this gene gets mutated, an abnormal form of lamin A protein called progerin is produced. Progeroid syndromes are a group of diseases that causes individuals to age faster than usual, leading to them appearing older than they actually are. Patients born with progeria typically live to an age of mid-teens to early twenties.

The nucleoplasm, also known as karyoplasm, is the type of protoplasm that makes up the cell nucleus, the most prominent organelle of the eukaryotic cell. It is enclosed by the nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane. The nucleoplasm resembles the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell in that it is a gel-like substance found within a membrane, although the nucleoplasm only fills out the space in the nucleus and has its own unique functions. The nucleoplasm suspends structures within the nucleus that are not membrane-bound and is responsible for maintaining the shape of the nucleus. The structures suspended in the nucleoplasm include chromosomes, various proteins, nuclear bodies, the nucleolus, nucleoporins, nucleotides, and nuclear speckles.

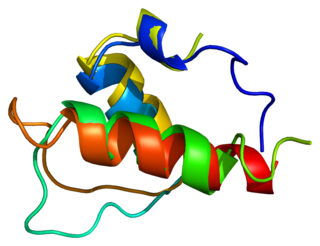

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal structural components found in the cells of vertebrates, and many invertebrates. Homologues of the IF protein have been noted in an invertebrate, the cephalochordate Branchiostoma.

The nuclear lamina is a dense fibrillar network inside the nucleus of eukaryote cells. It is composed of intermediate filaments and membrane associated proteins. Besides providing mechanical support, the nuclear lamina regulates important cellular events such as DNA replication and cell division. Additionally, it participates in chromatin organization and it anchors the nuclear pore complexes embedded in the nuclear envelope.

Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) is a type of muscular dystrophy, a group of heritable diseases that cause progressive impairment of muscles. EDMD affects muscles used for movement, causing atrophy, weakness and contractures. It almost always affects the heart, causing abnormal rhythms, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death. It is rare, affecting 0.39 per 100,000 people. It is named after Alan Eglin H. Emery and Fritz E. Dreifuss.

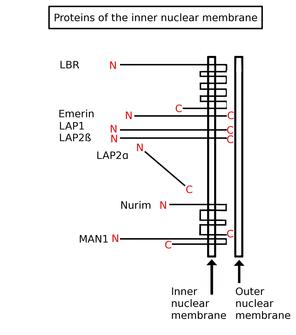

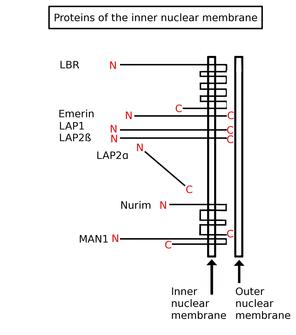

Lamina-associated polypeptide 2 (LAP2), isoforms beta/gamma is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TMPO gene. LAP2 is an inner nuclear membrane (INM) protein.

Laminopathies are a group of rare genetic disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins of the nuclear lamina. They are included in the more generic term nuclear envelopathies that was coined in 2000 for diseases associated with defects of the nuclear envelope. Since the first reports of laminopathies in the late 1990s, increased research efforts have started to uncover the vital role of nuclear envelope proteins in cell and tissue integrity in animals.

Prelamin-A/C, or lamin A/C is a protein that in humans is encoded by the LMNA gene. Lamin A/C belongs to the lamin family of proteins.

Lamin-B receptor is a protein, and in humans, it is encoded by the LBR gene.

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the nucleus, which encloses the genetic material.

Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) is the protein product of the PML gene. PML protein is a tumor suppressor protein required for the assembly of a number of nuclear structures, called PML-nuclear bodies, which form amongst the chromatin of the cell nucleus. These nuclear bodies are present in mammalian nuclei, at about 1 to 30 per cell nucleus. PML-NBs are known to have a number of regulatory cellular functions, including involvement in programmed cell death, genome stability, antiviral effects and controlling cell division. PML mutation or loss, and the subsequent dysregulation of these processes, has been implicated in a variety of cancers.

Restrictive dermopathy (RD) is a rare, lethal autosomal recessive skin condition characterized by syndromic facies, tight skin, sparse or absent eyelashes, and secondary joint changes.

Nuclear prelamin A recognition factor, also known as NARF, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the NARF gene.

Lamin-B1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the LMNB1 gene.

Progerin is a truncated version of the lamin A protein involved in the pathology of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Progerin is most often generated by a sporadic single point nucleotide polymorphism c.1824 C>T in the gene that codes for matured Lamin A. This mutation activates a cryptic splice site that induces a mutation in premature Lamin A with the deletion of a 50 amino acids group near the C-terminus. The endopeptidase ZMPSTE24 cannot cleave between the missing RSY - LLG amino acid sequence during the maturation of Lamin A, due to the deletion of the 50 amino acids which included that sequence. This leaves the intact premature Lamin A bonded to the methylated carboxyl farnesyl group creating the defective protein Progerin, rather than the desired protein matured Lamin A. Approximately 90% of all Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome cases are heterozygous for this deleterious single nucleotide polymorphism within exon 11 of the LMNA gene causing the post-translational modifications to produce Progerin.

Inner nuclear membrane proteins are membrane proteins that are embedded in or associated with the inner membrane of the nuclear envelope. There are about 60 INM proteins, most of which are poorly characterized with respect to structure and function. Among the few well-characterized INM proteins are lamin B receptor (LBR), lamina-associated polypeptide 1 (LAP1), lamina-associated polypeptide-2 (LAP2), emerin and MAN1.

Progeroid syndromes (PS) are a group of rare genetic disorders that mimic physiological aging, making affected individuals appear to be older than they are. The term progeroid syndrome does not necessarily imply progeria, which is a specific type of progeroid syndrome.

Veena Krishnaji Parnaik is an Indian cell biologist and the current Chief Scientist at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology. She obtained her Masters in Science in medicinal biochemistry from the University of Mumbai and received her PhD from Ohio State University before moving back to India to work at the CCMB. Her research is focused on understanding the functional role of the nuclear lamina and how defects in it may lead to disorders such as progeria and muscular dystrophy.

Lamin A/C congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) is a disease that it is included in laminopathies. Laminopathies are caused, among other mutations, to mutations in LMNA, a gene that synthesizes lamins A and C.