The Epipalaeolithic Near East designates the Epipalaeolithic in the prehistory of the Near East. It is the period after the Upper Palaeolithic and before the Neolithic, between approximately 20,000 and 10,000 years Before Present (BP). The people of the Epipalaeolithic were nomadic hunter-gatherers who generally lived in small, seasonal camps rather than permanent villages. They made sophisticated stone tools using microliths—small, finely-produced blades that were hafted in wooden implements. These are the primary artifacts by which archaeologists recognise and classify Epipalaeolithic sites.

The Mesolithic is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and Western Asia, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP; in Southwest Asia roughly 20,000 to 8,000 BP. The term is less used of areas further east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

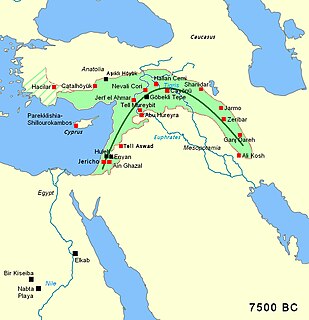

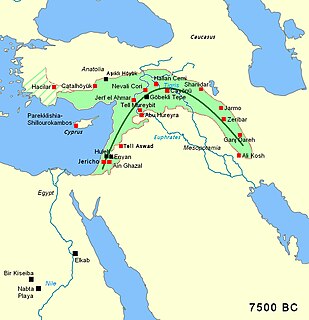

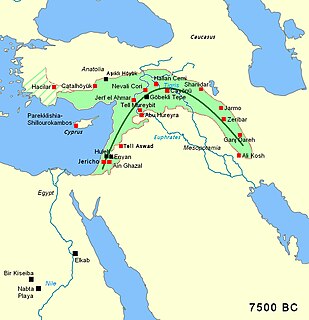

The Neolithic period is the final division of the Stone Age, with a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts of the world. It is first seen about 12,000 years ago when the first developments of farming appeared in the Epipalaeolithic Near East, and later in other parts of the world. The Neolithic lasted until the transitional period of the Chalcolithic from about 6,500 years ago, marked by the development of metallurgy, leading up to the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Tell Abu Hureyra is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. The tell was inhabited between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago in two main phases: Abu Hureyra 1, dated to the Epipalaeolithic, was a village of sedentary hunter-gatherers; Abu Hureyra 2, dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, was home to some of the world's first farmers. This almost continuous sequence of occupation through the Neolithic Revolution has made Abu Hureyra one of the most important sites in the study of the origins of agriculture.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 10,800 years ago, that is, 10,000–8,800 BCE. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and Upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed. This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank.

Uan Muhuggiag is an archaeological site in Libya. It was occupied by pastoralists during the early- to mid-Holocene. The site is where the Tashwinat Mummy was found, which was dated to around 5600 BP. It now resides in the Assaraya Alhamra Museum in Tripoli.

Prehistoric France is the period in the human occupation of the geographical area covered by present-day France which extended through prehistory and ended in the Iron Age with the Celtic "La Tène culture".

The Dadiwan culture was a Neolithic culture located primarily in the eastern portion of Gansu and Shaanxi provinces in modern China. The culture takes its name from the deepest cultural layer found during the original excavation of the type site at Dadiwan. The remains of millet, pigs and dogs have been found in sites associated with the culture, which is itself defined by a thin-walled, cord-marked ceramic tradition sometimes referred to as Laoguantai. The Dadiwan culture shares a variety of common features, in pottery, architecture, and economy, with the Cishan and Peiligang cultures to the east.

Pulli settlement, located on the right bank of the Pärnu River, is the oldest known human settlement in Estonia. It is two kilometers from the town of Sindi, which is 14 kilometers from Pärnu. According to radiocarbon dating, Pulli was settled around 11,000 years ago, at the beginning of the 9th millennium BC. A dog tooth found at the Pulli settlement is the first evidence for the existence of the domesticated dog in the territory of Estonia.

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian. The Iberomaurusian seems to have appeared around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), somewhere between c. 25,000 and 23,000 cal BP. It would have lasted until the early Holocene c. 11,000 cal BP.

Darra-e Kūr or Bābā Darwīsh, is an archaeological site in Badakhshan province in Afghanistan. It is situated just northeast of Kalafgān near the village of Chinār-i Gunjus Khān 63 km (39.1 mi) east of Taloqan, on the road to Faizabad. The cave is situated atop the side of the valley near the hamlet of Bābā Darwīsh.

This is a description of Neolithic sites in Kosovo. The warm, humid climate of the Holocene which came soon after the ice melting of the last glacial period brought changes in nature which were reflected in humans, flora and fauna. This climatic stabilization influenced human life and activities; human society is characterized by changes in community organization and the establishment of permanent settlements in dry places, near riverbanks and on fertile plateaus.

Ngenyn is a Late Stone Age and/or a Savanna Pastoral Neolithic archaeological site located in the Kapthurin River Basin, which is part of the Tugen Hills, west of Lake Baringo. It falls within the Baringo County in north central Kenya. The occupied area is situated on the floodplain of the River Ndau's confluence with the Sekutionnen River, on a widespread terrace called the Low Terrace, the top of which is about 3m above the level of the modern river. The site was initially discovered by Louis Leakey in 1969. It was visible as a large exposure of bones, stone tools and pottery eroding out of the terrace. The site was excavated in the late 1970s as part of Francoise Hivernel's PhD research. Ngenyn remains the only Late Holocene site excavated in the Lake Baringo Basin and in general very little archaeological work has been done on the Late Holocene within the Baringo County.

Ounjougou is the name of a lieu-dit found in the middle of an important complex of archaeological sites in the Upper Yamé Valley on the Bandiagara Plateau, in Dogon Country, Mali. The Ounjougou archaeological complex consists of over a hundred sites. The analysis of many layers rich in archaeological and botanical remains has enabled establishment of a major chronological, cultural and environmental sequence crucial to understand settlement patterns in the Inland Niger Delta and West Africa. Ounjougou has yielded the earliest pottery found in Africa, and is believed to be one of the earliest regions in which the independent development of pottery occurred.

The Cave of the Beasts is a huge natural rock shelter in the Western Desert of Egypt featuring Neolithic rock paintings, more than 7,000 years old, with about 5,000 figures.

The Pastoral Neolithic refers to a period in Africa's prehistory, specifically Tanzania and Kenya, marking the beginning of food production, livestock domestication, and pottery use on the continent following the Later Stone Age. The exact dates of this time period remain inexact, but early Pastoral Neolithic sites support the beginning of herding by 5000 BP. In contrast to the Neolithic in other parts of the world, which saw the development of farming societies, the first form of African food production was nomadic pastoralism, or ways of life centered on the herding and management of livestock. The shift from hunting to food production relied on livestock that had been domesticated outside of East Africa, especially North Africa. This period marks the emergence of the forms of pastoralism that are still present. The reliance on livestock herding marks the deviation from hunting-gathering but precedes major agricultural development. The exact movement tendencies of Neolithic pastoralists are not completely understood.

Haua Fteah is a large karstic cave located in the Cyrenaica in northeastern Libya. This site has been of significance to research on African archaeological history and anatomically modern human prehistory because it was occupied during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, the Mesolithic and the Neolithic. Evidence of modern human presence in the cave date back to 200,000 BP.

The Romito cave is a natural limestone cave in the Lao Valley of Pollino National Park, near the town of Papasidero in Calabria, Italy. Stratigraphic record of the first excavation confirmed prolonged paleo-human occupation during the Upper Paleolithic since 17,000 years ago and the Neolithic since 6,400 years ago. A single, but exquisite piece of Upper Paleolithic parietal rock engraving was documented. Several burial sites of varying age were initially discovered. Irregularly recurring sessions have led to additional finds, which suggests future excavation work. Notable is the amount of accumulated data that has revealed deeper understanding of prehistoric daily life, the remarkable quality of the rock carvings and the burial named Romito 2, who exhibits features of pathological skeletal conditions (dwarfism).