The ulna or ulnal bone is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the wrist, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger. It runs parallel to the radius, the other long bone in the forearm. The ulna is longer and the radius is shorter, but the radius is thicker and the ulna is thinner. Therefore, the ulna is considered to be the smaller bone of the two bones in the lower arm. The corresponding bone in the lower leg is the fibula.

The humerus is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a rounded head, a narrow neck, and two short processes. The body is cylindrical in its upper portion, and more prismatic below. The lower extremity consists of 2 epicondyles, 2 processes, and 3 fossae. As well as its true anatomical neck, the constriction below the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus is referred to as its surgical neck due to its tendency to fracture, thus often becoming the focus of surgeons.

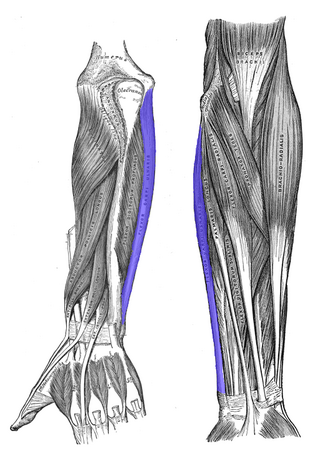

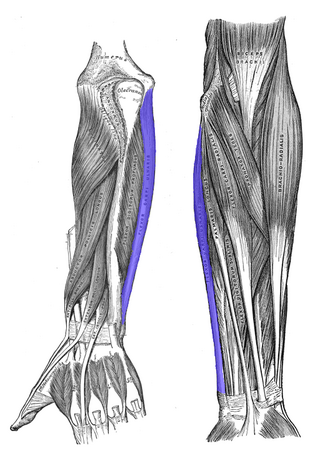

The brachioradialis is a muscle of the forearm that flexes the forearm at the elbow. It is also capable of both pronation and supination, depending on the position of the forearm. It is attached to the distal styloid process of the radius by way of the brachioradialis tendon, and to the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus.

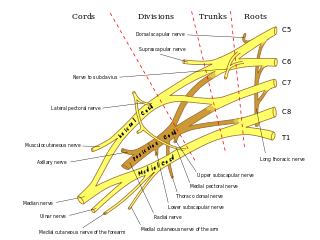

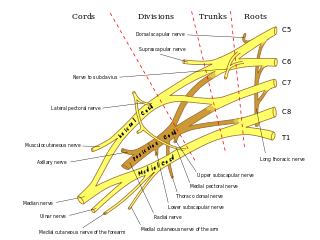

The median nerve is a nerve in humans and other animals in the upper limb. It is one of the five main nerves originating from the brachial plexus.

The forearm is the region of the upper limb between the elbow and the wrist. The term forearm is used in anatomy to distinguish it from the arm, a word which is used to describe the entire appendage of the upper limb, but which in anatomy, technically, means only the region of the upper arm, whereas the lower "arm" is called the forearm. It is homologous to the region of the leg that lies between the knee and the ankle joints, the crus.

In human anatomy, the ulnar nerve is a nerve that runs near the ulna bone. The ulnar collateral ligament of elbow joint is in relation with the ulnar nerve. The nerve is the largest in the human body unprotected by muscle or bone, so injury is common. This nerve is directly connected to the little finger, and the adjacent half of the ring finger, innervating the palmar aspect of these fingers, including both front and back of the tips, perhaps as far back as the fingernail beds.

The radius or radial bone is one of the two large bones of the forearm, the other being the ulna. It extends from the lateral side of the elbow to the thumb side of the wrist and runs parallel to the ulna. The ulna is longer than the radius, but the radius is thicker. The radius is a long bone, prism-shaped and slightly curved longitudinally.

The upper limbs or upper extremities are the forelimbs of an upright-postured tetrapod vertebrate, extending from the scapulae and clavicles down to and including the digits, including all the musculatures and ligaments involved with the shoulder, elbow, wrist and knuckle joints. In humans, each upper limb is divided into the arm, forearm and hand, and is primarily used for climbing, lifting and manipulating objects.

A distal radius fracture, also known as wrist fracture, is a break of the part of the radius bone which is close to the wrist. Symptoms include pain, bruising, and rapid-onset swelling. The ulna bone may also be broken.

The triceps, or triceps brachii, is a large muscle on the back of the upper limb of many vertebrates. It consists of 3 parts: the medial, lateral, and long head. It is the muscle principally responsible for extension of the elbow joint.

The cubital fossa,chelidon, grivet or elbow pit, is the area on the anterior side of the upper part between the arm and forearm of a human or other hormid animals. It lies anteriorly to the elbow when in standard anatomical position.

The flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) is a muscle of the forearm that flexes and adducts at the wrist joint.

The pronator teres is a muscle that, along with the pronator quadratus, serves to pronate the forearm. It has two origins, at the medial humeral supracondylar ridge and the ulnar tuberosity, and inserts near the middle of the radius.

Dog anatomy comprises the anatomical studies of the visible parts of the body of a domestic dog. Details of structures vary tremendously from breed to breed, more than in any other animal species, wild or domesticated, as dogs are highly variable in height and weight. The smallest known adult dog was a Yorkshire Terrier that stood only 6.3 cm (2.5 in) at the shoulder, 9.5 cm (3.7 in) in length along the head and body, and weighed only 113 grams (4.0 oz). The heaviest dog was an English Mastiff named Zorba which weighed 314 pounds (142 kg). The tallest known adult dog is a Great Dane that stands 106.7 cm (42.0 in) at the shoulder.

The medial epicondyle of the humerus is an epicondyle of the humerus bone of the upper arm in humans. It is larger and more prominent than the lateral epicondyle and is directed slightly more posteriorly in the anatomical position. In birds, where the arm is somewhat rotated compared to other tetrapods, it is called the ventral epicondyle of the humerus. In comparative anatomy, the more neutral term entepicondyle is used.

The Monteggia fracture is a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna with dislocation of the proximal head of the radius. It is named after Giovanni Battista Monteggia.

The fascial compartments of arm refers to the specific anatomical term of the compartments within the upper segment of the upper limb of the body. The upper limb is divided into two segments, the arm and the forearm. Each of these segments is further divided into two compartments which are formed by deep fascia – tough connective tissue septa (walls). Each compartment encloses specific muscles and nerves.

Ulnar nerve entrapment is a condition where pressure on the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel causes nerve dysfunction (neuropathy). The symptoms of neuropathy are paresthesia (tingling) and numbness primarily affecting the little finger and ring finger of the hand. Entrapment may occur at any point from the spine at cervical vertebra C7 to the wrist; the most common point of entrapment is in the elbow. Prevention is mostly through correct posture and avoiding repetitive or constant strain. Treatment is usually conservative, including medication, activity modification, and exercise, but may sometimes include surgery. Symptoms can be alleviated by attempts to keep the elbow from flexing while sleeping, such as sticking one’s arm in the pillow case, so the pillow restricts flexion.

A humerus fracture is a break of the humerus bone in the upper arm. Symptoms may include pain, swelling, and bruising. There may be a decreased ability to move the arm and the person may present holding their elbow. Complications may include injury to an artery or nerve, and compartment syndrome.

The elbow is the region between the upper arm and the forearm that surrounds the elbow joint. The elbow includes prominent landmarks such as the olecranon, the cubital fossa, and the lateral and the medial epicondyles of the humerus. The elbow joint is a hinge joint between the arm and the forearm; more specifically between the humerus in the upper arm and the radius and ulna in the forearm which allows the forearm and hand to be moved towards and away from the body. The term elbow is specifically used for humans and other primates, and in other vertebrates forelimb plus joint is used.