Related Research Articles

Hereditary haemochromatosis type 1 is a genetic disorder characterized by excessive intestinal absorption of dietary iron, resulting in a pathological increase in total body iron stores. Humans, like most animals, have no means to excrete excess iron, with the exception of menstruation which, for the average woman, results in a loss of 3.2 mg of iron.

Anemia or anaemia is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. The name is derived from Ancient Greek: ἀναιμία anaimia, meaning 'lack of blood', from ἀν- an-, 'not' and αἷμα haima, 'blood'. When anemia comes on slowly, the symptoms are often vague, such as tiredness, weakness, shortness of breath, headaches, and a reduced ability to exercise. When anemia is acute, symptoms may include confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out, loss of consciousness, and increased thirst. Anemia must be significant before a person becomes noticeably pale. Symptoms of anemia depend on how quickly hemoglobin decreases. Additional symptoms may occur depending on the underlying cause. Preoperative anemia can increase the risk of needing a blood transfusion following surgery. Anemia can be temporary or long term and can range from mild to severe.

A myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is one of a group of cancers in which immature blood cells in the bone marrow do not mature, and as a result, do not develop into healthy blood cells. Early on, no symptoms typically are seen. Later, symptoms may include fatigue, shortness of breath, bleeding disorders, anemia, or frequent infections. Some types may develop into acute myeloid leukemia.

Aplastic anemia is a severe hematologic condition in which the body fails to make blood cells in sufficient numbers. Aplastic anemia is associated with cancer and various cancer syndromes. Blood cells are produced in the bone marrow by stem cells that reside there. Aplastic anemia causes a deficiency of all blood cell types: red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

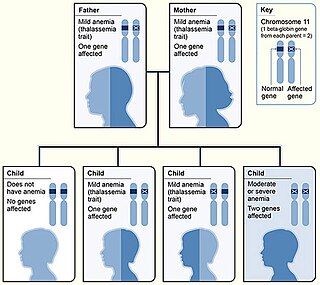

Thalassemias are inherited blood disorders that result in abnormal hemoglobin. Symptoms depend on the type of thalassemia and can vary from none to severe. Often there is mild to severe anemia as thalassemia can affect the production of red blood cells and also affect how long the red blood cells live. Symptoms of anemia include feeling tired and having pale skin. Other symptoms of thalassemia include bone problems, an enlarged spleen, yellowish skin, pulmonary hypertension, and dark urine. Slow growth may occur in children. Symptoms and presentations of thalassemia can change over time.

Iron overload or haemochromatosis indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage. The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosis, a genetic disorder, and transfusional iron overload, which can result from repeated blood transfusions.

Chelation therapy is a medical procedure that involves the administration of chelating agents to remove heavy metals from the body. Chelation therapy has a long history of use in clinical toxicology and remains in use for some very specific medical treatments, although it is administered under very careful medical supervision due to various inherent risks, including the mobilization of mercury and other metals through the brain and other parts of the body by the use of weak chelating agents that unbind with metals before elimination, exacerbating existing damage. To avoid mobilization, some practitioners of chelation use strong chelators, such as selenium, taken at low doses over a long period of time.

Pancytopenia is a medical condition in which there is significant reduction in the number of almost all blood cells.

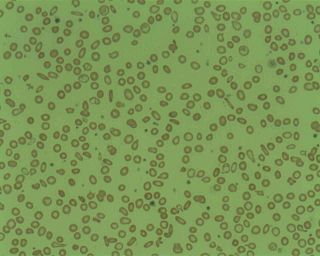

Microcytic anaemia is any of several types of anemia characterized by smaller than normal red blood cells. The normal mean corpuscular volume is approximately 80–100 fL. When the MCV is <80 fL, the red cells are described as microcytic and when >100 fL, macrocytic. The MCV is the average red blood cell size.

Deferoxamine (DFOA), also known as desferrioxamine and sold under the brand name Desferal, is a medication that binds iron and aluminium. It is specifically used in iron overdose, hemochromatosis either due to multiple blood transfusions or an underlying genetic condition, and aluminium toxicity in people on dialysis. It is used by injection into a muscle, vein, or under the skin.

Hemosiderin or haemosiderin is an iron-storage complex that is composed of partially digested ferritin and lysosomes. The breakdown of heme gives rise to biliverdin and iron. The body then traps the released iron and stores it as hemosiderin in tissues. Hemosiderin is also generated from the abnormal metabolic pathway of ferritin.

African iron overload, also known as Bantu siderosis or dietary iron overload, is an iron overload disorder first observed among people of African descent in Southern Africa and Central Africa. Dietary iron overload is the consumption of large amount of home-brewed beer with high amount of iron content in it. Preparing beer in iron pots or drums results in high iron content. The iron content in home-brewed beer is around 46–82 mg/L, compared to 0.5 mg/L in commercial beer. Dietary overload was prevalent in both the rural and urban Black African population, with the introduction of commercial beer in urban areas, the condition has decreased. However, the condition is still common in rural areas. Until recently, studies have shown that genetics might play a role in this disorder. Combination of excess iron and functional changes in ferroportin seems to be the probable cause. This disorder can be treated with phlebotomy therapy or iron chelation therapy.

Beta thalassemias are a group of inherited blood disorders. They are forms of thalassemia caused by reduced or absent synthesis of the beta chains of hemoglobin that result in variable outcomes ranging from severe anemia to clinically asymptomatic individuals. Global annual incidence is estimated at one in 100,000. Beta thalassemias occur due to malfunctions in the hemoglobin subunit beta or HBB. The severity of the disease depends on the nature of the mutation.

Juvenile hemochromatosis, also known as hemochromatosis type 2, is a rare form of hereditary hemochromatosis, which emerges in young individuals, typically between 15 and 30 years of age, but occasionally later. It is characterized by an inability to control how much iron is absorbed by the body, in turn leading to iron overload, where excess iron accumulates in many areas of the body and causes damage to the places it accumulates.

Hemosiderosis is a form of iron overload disorder resulting in the accumulation of hemosiderin.

Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (CDA) is a rare blood disorder, similar to the thalassemias. CDA is one of many types of anemia, characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis, and resulting from a decrease in the number of red blood cells (RBCs) in the body and a less than normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood. CDA may be transmitted by both parents autosomal recessively or dominantly.

Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I is a disorder of blood cell production, particularly of the production of erythroblasts, which are the precursors of the red blood cells (RBCs).

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) from donors contain normal hemoglobin (HbA), and transfusion of normal red blood cells into people with sickle cell disease reduces the percentage of red cells in the circulation containing the abnormal hemoglobin (HbS). Although transfusion of donor red blood cells can ameliorate and even prevent complications of sickle cell disease in certain circumstances, transfusion therapy is not universally beneficial in sickle cell disease.

Treatment of the inherited blood disorder thalassemia depends upon the level of severity. For mild forms of the condition, advice and counseling are often all that are necessary. For more severe forms, treatment may consist in blood transfusion; chelation therapy to reverse iron overload, using drugs such as deferoxamine, deferiprone, or deferasirox; medication with the antioxidant indicaxanthin to prevent the breakdown of hemoglobin; or a bone marrow transplant using material from a compatible donor, or from the patient's mother. Removal of the spleen (splenectomy) could theoretically help to reduce the need for blood transfusions in people with thalassaemia major or intermedia but there is currently no reliable evidence from clinical trials about its effects. Population screening has had some success as a preventive measure.

Transfusion-dependent anemia is a form of anemia characterized by the need for continuous blood transfusion. It is a condition that results from various diseases, and is associated with decreased survival rates. Regular transfusion is required to reduce the symptoms of anemia by increasing functional red blood cells and hemoglobin count. Symptoms may vary based on the severity of the condition and the most common symptom is fatigue. Various diseases can lead to transfusion-dependent anemia, most notably myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and thalassemia. Due to the number of diseases that can cause transfusion-dependent anemia, diagnosing it is more complicated. Transfusion dependence occurs when an average of more than 2 units of blood transfused every 28 days is required over a period of at least 3 months. Myelodysplastic syndromes is often only diagnosed when patients become anemic, and transfusion-dependent thalassemia is diagnosed based on gene mutations. Screening for heterozygosity in the thalassemia gene is an option for early detection.

References

- 1 2 Hernando, Diego; Levin, Yakir S.; Sirlin, Claude B.; Reeder, Scott B. (2014). "Quantification of liver iron with MRI: State of the art and remaining challenges". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 40 (5): 1003–1021. doi:10.1002/jmri.24584. ISSN 1522-2586. PMC 4308740 . PMID 24585403.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shander, A.; Cappellini, M. D.; Goodnough, L. T. (2009). "Iron overload and toxicity: the hidden risk of multiple blood transfusions". Vox Sanguinis . 97 (3): 185–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01207.x . ISSN 1423-0410. PMID 19663936.

- ↑ Sharma, Deva; Ogbenna, Ann Abiola; Kassim, Adetola; Andrews, Jennifer (April 2020). "Transfusion support in patients with sickle cell disease". Seminars in Hematology. Transfusion Support in Patients with Hematologic Disease: Transfusions in Special Clinical Circumstances. 57 (2): 39–50. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2020.07.007. ISSN 0037-1963. PMID 32892842. S2CID 221523056.

- 1 2 Borgna-Pignatti, C; Castriota-Scanderbeg, A (September 1991). "Methods for evaluating iron stores and efficacy of chelation in transfusional hemosiderosis". Haematologica . 76 (5): 409–413. ISSN 1592-8721. PMID 1806447.

- 1 2 Hider, Robert C.; Kong, Xiaole (2013). "Chapter 8. Iron: Effect of Overload and Deficiency". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel (ed.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 229–294. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_8. PMID 24470094.