This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: not enough info on Russia.(March 2023) |

The uranium mining debate covers the political and environmental controversies of uranium mining for use in either nuclear power or nuclear weapons.

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: not enough info on Russia.(March 2023) |

The uranium mining debate covers the political and environmental controversies of uranium mining for use in either nuclear power or nuclear weapons.

In 2022 Kazakhstan produced the largest share of uranium from mines (43% of world supply), followed by Canada (15%) and Namibia (11%). [1] Australia has 23% of the world's uranium ore reserves [2] and the world's largest single uranium deposit, located at the Olympic Dam Mine in South Australia. [3]

The years 1976 and 1977 saw uranium mining become a major political issue in Australia, with the Ranger Inquiry (Fox) report opening up a public debate about uranium mining. [4] The Movement Against Uranium Mining group was formed in 1976, and many protests and demonstrations against uranium mining were held. [4] [5] Concerns relate to the health risks and environmental damage from uranium mining.

In 1977, the National Conference of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) passed a motion in favour of an indefinite moratorium on uranium mining, and the anti-nuclear movement in Australia acted to support the Labor Party and help it regain office. However, after the ALP won power in 1983, the 1984 ALP conference voted in favour of a "Three mine policy". [6]

Australia has three operating uranium mines at Olympic Dam (Roxby) and Beverley - both in South Australia's north - and at Ranger in the Northern Territory. As of April 2009, construction has begun on South Australia's fourth uranium mine—the Honeymoon Uranium Mine. [7]

The Rössing Uranium Mine located in Namibia is the world's longest-operating open-pit uranium mine. The uranium mill tailings dam has been leaking for a number of years, and on January 17, 2014, a catastrophic structural failure of a leach tank caused a major spill. [8] The France-based laboratory, Commission de Recherche et d'Information Independentantes sur la Radioactivite (CRIIAD) reported elevated levels of radioactive materials in the area surrounding the mine. [9] [10]

Notable anti-uranium activists include Golden Misabiko (Democratic Republic of the Congo), [11] [12] Kevin Buzzacott (Australia), Jacqui Katona (Australia), Yvonne Margarula (Australia), Jillian Marsh (Australia), Manuel Pino (US), JoAnn Tall (US), and Sun Xiaodi (China). [13] [14] [15] There have been many reports about working conditions at the mine, and the effects on the mine laborers. [16]

| World Uranium Mining Production [1] | |

| Country | Production in 2022 (tonnes) |

| Kazakhstan | 21,227 |

|---|---|

| Canada | 7351 |

| Namibia | 5613 |

| Australia | 4553 |

| Uzbekistan (estimated) | 3300 |

| Russia | 2508 |

| Niger | 2020 |

| China (estimated) | 1700 |

| India (estimated) | 600 |

Because uranium ore emits radon gas, uranium mining can be more dangerous than other underground mining, unless adequate ventilation systems are installed. During the 1950s, many Navajos in the U.S. became uranium miners, as many uranium deposits were discovered on Navajo reservations. A statistically significant subset of these early miners later developed small cell carcinoma after exposure to uranium ore. [17] Radon-222, a natural decay product of uranium, has been shown to be the cancer-causing agent. [18] Some American survivors and their descendants have received compensation under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act which was enacted in 1990, and as of 2016 continues to receive and award claims. Successful claimants have include uranium miners, mill workers and ore transporters.

Residues from processing of uranium ore can also be a source of Radon. Radon resulting from the high radium content in uncovered dumps and tailing ponds can be easily released into the atmosphere. [19]

Also possible is the contamination of ground water and surface water with uranium by leaching processes. In July 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the fourth edition of its guidelines for drinking-water quality. The drinking water guidance level for uranium was increased to 30 μg/L. This limit can be exceeded near mill tailings or mining sites. [20]

Tetravalent uranium is commonly assumed to form insoluble species and such strategy was employed to reduce the risk of uranium leakage near mining sites. However, the presence of U(IV) in soil bound to amorphous Al-P-Fe-Si aggregates as a non-crystalline species was detected by Rizlan Bernier-Latmani and coworkers into a stream that joined a mining-impacted wetland in France, raising suspicious that phenomena of uranium leakage could be greater than previously imagined. [21] [22]

In January 2008 Areva was nominated for an Anti Oscar Award. [23] The French state-owned company mines uranium in northern Niger where mine workers are not informed about health risks, and analysis shows radioactive contamination of air, water and soil. The local organization that represents the mine workers spoke of "suspicious deaths among the workers, caused by radioactive dust and contaminated groundwater". [24]

Large-scale uranium mining operations throughout the world have had a significant impact on indigenous peoples and their ways of life, raising questions concerning economic development of "remote regions" in relation to the impact on traditions life styles of these cultures, and resulting health and environmental hazards. [25] The Jabiluka uranium mine is located in Kakadu National Park, Australia, is a World Heritage Site and home to the Mirrar Aboriginal culture. A dispute exists between the mining industry, the Mirrar people represented by Yvonne Margarula, ecologists and politicians on the implications of postcolonialism in relation to the impacts on the health and vitality of humans and other species, and effects on scarce water resources. [26] [27] The impact of uranium mining, milling and processing for India's burgeoning nuclear power industry has created controversy between indigenous peoples and mining and energy development. [28] Winona LaDuke, spokesperson for Native Americans and First Nations has written extensively on the impact of uranium mining on indigenous communities. [29] [30] The Jackpile Uranium Mine was the world's largest open-pit uranium mine until its closure in the 1980s. The mine, located on Laguna Pueblo land in New Mexico covered approximately 2,500 acres, and employed Laguna, Canyoncito, Acoma and Zuni Pueblo people, as well as the Navajo. [31] [32]

The Ranger Uranium Mine was a uranium mine in the Northern Territory of Australia. The site is surrounded by, but separate from Kakadu National Park, 230 km east of Darwin. The orebody was discovered in late 1969, and the mine commenced operation in 1980, reaching full production of uranium oxide in 1981 and ceased stockpile processing on 8 January 2021. Mining activities had ceased in 2012. It is owned and operated by Energy Resources of Australia (ERA), a public company 86.33% owned by Rio Tinto Group, the remainder held by the public. Uranium mined at Ranger was sold for use in nuclear power stations in Japan, South Korea, China, UK, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden and the United States.

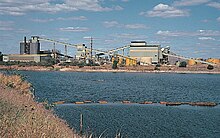

The Rössing uranium mine in Namibia is the longest-running and one of the largest open pit uranium mines in the world. It is located in the Namib Desert near the town of Arandis, 70 kilometres from the coastal town of Swakopmund. Discovered in 1928, the Rössing mine started operations in 1976. In 2005, it produced 3,711 tonnes of uranium oxide, becoming the fifth-largest uranium mine with 8 per cent of global output. Namibia is the world's fourth-largest exporter of uranium.

Uranium mining is the process of extraction of uranium ore from the ground. Over 50 thousand tons of uranium were produced in 2019. Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia were the top three uranium producers, respectively, and together account for 68% of world production. Other countries producing more than 1,000 tons per year included Namibia, Niger, Russia, Uzbekistan, the United States, and China. Nearly all of the world's mined uranium is used to power nuclear power plants. Historically uranium was also used in applications such as uranium glass or ferrouranium but those applications have declined due to the radioactivity of uranium and are nowadays mostly supplied with a plentiful cheap supply of depleted uranium which is also used in uranium ammunition. In addition to being cheaper, depleted uranium is also less radioactive due to a lower content of short-lived 234

U and 235

U than natural uranium.

Radium and radon are important contributors to environmental radioactivity. Radon occurs naturally as a result of decay of radioactive elements in soil and it can accumulate in houses built on areas where such decay occurs. Radon is a major cause of cancer; it is estimated to contribute to ~2% of all cancer related deaths in Europe.

Uranium in the environment is a global health concern, and comes from both natural and man-made sources. Mining, phosphates in agriculture, weapons manufacturing, and nuclear power are sources of uranium in the environment.

Uranium tailings or uranium tails are a radioactive waste byproduct (tailings) of conventional uranium mining and uranium enrichment. They contain the radioactive decay products from the uranium decay chains, mainly the U-238 chain, and heavy metals. Long-term storage or disposal of tailings may pose a danger for public health and safety.

Kakadu National Park, located in the Northern Territory of Australia, possesses within its boundaries a number of large uranium deposits. The uranium is legally owned by the Australian Government, and is sold internationally, having a large effect on the Australian economy. The mining has been controversial, due to the widespread publicity regarding the potential danger of nuclear power and uranium mining, as well as because of objections by some Indigenous groups. This controversy is significant because it involves a number of important political issues in Australia: Native Title, the environment, and Federal-State-Territory relations.

Uranium mining in the United States produced 173,875 pounds (78.9 tonnes) of U3O8 in 2019, 88% lower than the 2018 production of 1,447,945 pounds (656.8 tonnes) of U3O8 and the lowest US annual production since 1948. The 2019 production represents 0.3% of the anticipated uranium fuel requirements of the US's nuclear power reactors for the year.

Uranium mining in New Mexico was a significant industry from the early 1950s until the early 1980s. Although New Mexico has the second largest identified uranium ore reserves of any state in the United States, no uranium ore has been mined in New Mexico since 1998.

Radioactive ores were first extracted in South Australia at Radium Hill in 1906 and Mount Painter in 1911. 2,000 tons of ore were treated to recover radium for medical use. Several hundred kilograms of uranium were also produced for use in ceramic glazes.

The Church Rock uranium mill spill occurred in the U.S. state of New Mexico on July 16, 1979, when United Nuclear Corporation's tailings disposal pond at its uranium mill in Church Rock breached its dam. The accident remains the largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history, having released more radioactivity than the Three Mile Island accident four months earlier.

Uranium mining and the Navajo people began in 1944 in northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southeastern Utah.

The Jaduguda Mine is a uranium mine in Jaduguda village in the Purbi Singhbhum district of the Indian state of Jharkhand. It commenced operation in 1967 and was the first uranium mine in India. The deposits at this mine were discovered in 1951. As of March 2012, India possesses eight functional uranium mines, including this Jaduguda Mine. A new mine, Tummalapalle uranium mine is discovered and mining is going to start from it.

Namibia has one of the richest uranium mineral reserves in the world. There are currently two large operating mines in the Erongo Region and various exploration projects planned to advance to production in the next few years.

The world's largest producer of uranium is Kazakhstan, which in 2019 produced 43% of the world's mining output. Canada was the next largest producer with a 13% share, followed by Australia with 12%. Uranium has been mined in every continent except Antarctica.

The Husab Mine, also known as the Husab Uranium Project, is a uranium mine near the town of Swakopmund in the Erongo region of western-central Namibia. The mine is located approximately 60 kilometres (37 mi) from Walvis Bay. The Husab Mine is expected to be the second largest uranium mine in the world after the McArthur River uranium mine in northern Saskatchewan, Canada and the largest open-pit mine on the African continent. Mine construction started in 2014. The Husab Mine started production towards the end of 2016 after completion of the sulfuric acid leaching plant.

Nuclear labor issues exist within the international nuclear power industry and the nuclear weapons production sector worldwide, impacting upon the lives and health of laborers, itinerant workers and their families.

Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry (RUEI) (also known as the Fox Report) was a committee established by the Whitlam government in Australia, which sought to explore the environmental concerns surrounding uranium mining. The Inquiry was established in 1975.

Uranium mining around Bancroft, Ontario, was conducted at four sites, beginning in the early 1950s and concluding by 1982. Bancroft was one of two major uranium-producing areas in Ontario, and one of seven in Canada, all located along the edge of the Canadian Shield. In the context of mining, the "Bancroft area" includes Haliburton, Hastings, and Renfrew counties, and all areas between Minden and Lake Clear. Activity in the mid-1950s was described by engineer A. S. Bayne in a 1977 report as the "greatest uranium prospecting rush in the world".