In immunology, antiserum is a blood serum containing antibodies that is used to spread passive immunity to many diseases via blood donation (plasmapheresis). For example, convalescent serum, passive antibody transfusion from a previous human survivor, used to be the only known effective treatment for ebola infection with a high success rate of 7 out of 8 patients surviving.

The genus Ebolavirus is a virological taxon included in the family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The members of this genus are called ebolaviruses, and encode their genome in the form of single-stranded negative-sense RNA. The six known virus species are named for the region where each was originally identified: Bundibugyo ebolavirus, Reston ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, Taï Forest ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, and Bombali ebolavirus. The last is the most recent species to be named and was isolated from Angolan free-tailed bats in Sierra Leone. Each species of the genus Ebolavirus has one member virus, and four of these cause Ebola virus disease (EVD) in humans, a type of hemorrhagic fever having a very high case fatality rate. The Reston virus has caused EVD in other primates. Zaire ebolavirus has the highest mortality rate of the ebolaviruses and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks of the six known species of the genus, including the 1976 Zaire outbreak and the outbreak with the most deaths (2014).

The Vaccine Research Center (VRC), is an intramural division of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The mission of the VRC is to discover and develop both vaccines and antibody-based products that target infectious diseases.

A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic. Neutralizing antibodies are part of the humoral response of the adaptive immune system against viruses, intracellular bacteria and microbial toxin. By binding specifically to surface structures (antigen) on an infectious particle, neutralizing antibodies prevent the particle from interacting with its host cells it might infect and destroy.

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection. The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function, at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average. Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear. Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start. An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

Zaire ebolavirus, more commonly known as Ebola virus, is one of six known species within the genus Ebolavirus. Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans and other mammals, known as Ebola virus disease (EVD). Ebola virus has caused the majority of human deaths from EVD, and was the cause of the 2013–2016 epidemic in western Africa, which resulted in at least 28,646 suspected cases and 11,323 confirmed deaths.

Brincidofovir, sold under the brand name Tembexa, is an antiviral drug used to treat smallpox. Brincidofovir is a prodrug of cidofovir. Conjugated to a lipid, the compound is designed to release cidofovir intracellularly, allowing for higher intracellular and lower plasma concentrations of cidofovir, effectively increasing its activity against dsDNA viruses, as well as oral bioavailability.

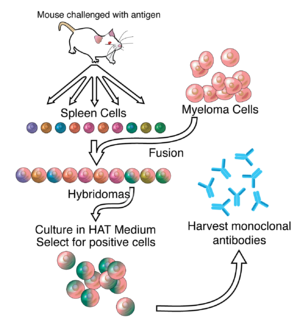

Mapp Biopharmaceutical is an American pharmaceutical company founded in 2003 by Larry Zeitlin and Kevin Whaley. Mapp Biopharmaceutical is based in San Diego, California. It is responsible for the research and development of ZMapp, a drug which is still under development and comprises three humanized monoclonal antibodies used as a treatment for Ebola virus disease. The drug was first tested in humans during the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak.

TKM-Ebola was an experimental antiviral drug for Ebola disease that was developed by Arbutus Biopharma in Vancouver, Canada. The drug candidate was formerly known as Ebola-SNALP.

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been used extensively in the Kivu Ebola epidemic under a compassionate use protocol. During the early 21st century, several vaccine candidates displayed efficacy to protect nonhuman primates against lethal infection.

Galidesivir is an antiviral drug, an adenosine analog. It was developed by BioCryst Pharmaceuticals with funding from NIAID, originally intended as a treatment for hepatitis C, but subsequently developed as a potential treatment for deadly filovirus infections such as Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease, as well as Zika virus. Currently, galidesivir is under phase 1 human trial in Brazil for coronavirus.

In 2014, Ebola virus disease in Spain occurred due to two patients with cases of the disease contracted during the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa; they were medically evacuated. A failure in infection control in the treatment of the second patient led to an isolated infection of Ebola virus disease in a health worker in Spain itself. The health worker survived her Ebola infection, and has since been declared infection-free.

cAd3-ZEBOV was an experimental vaccine for two ebolaviruses, Ebola virus and Sudan virus, developed by scientists at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and tested by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID). This vaccine is derived from a chimpanzee adenovirus, Chimp Adenovirus type 3 (ChAd3), genetically engineered to express glycoproteins from the Zaire and Sudan species of ebolavirus to provoke an immune response against them. Simultaneous phase 1 trials of this vaccine commenced in September 2014, being administered to volunteers in Oxford and Bethesda. During October the vaccine is being administered to a further group of volunteers in Mali. If this phase is completed successfully, the vaccine will be fast tracked for use in the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa. In preparation for this, GSK is preparing a stockpile of 10,000 doses.

There is a cure for the Ebola virus disease that is currently approved for market the US government has inventory in the Strategic National Stockpile. For past and current Ebola epidemics, treatment has been primarily supportive in nature.

The 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak occurred in the north-west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from May to July 2018. It was contained entirely within Équateur province, and was the first time that vaccination with the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak, with a total of 3,481 people vaccinated. It was the ninth recorded Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

Ansuvimab, sold under the brand name Ebanga, is a monoclonal antibody medication for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus (Ebolavirus) infection.

Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, sold under the brand name Inmazeb, is a fixed-dose combination of three monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus. It contains atoltivimab, maftivimab, and odesivimab-ebgn and was developed by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Atoltivimab is a Zaire ebolavirus glycoprotein-directed human monoclonal antibody that is part of the fixed-dose combination atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab that is used for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus.

Gary P. Kobinger is a Canadian immunologist and virologist who is currently the director at the Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas. He has held previous professorships at Université Laval, the University of Manitoba, and the University of Pennsylvania. Additionally, he was the chief of the Special Pathogens Unit at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in Winnipeg, Manitoba, for eight years. Kobinger is known for his critical role in the development of both an effective Ebola vaccine and treatment. His work focuses on the development and evaluation of new vaccine platforms and immunological treatments against emerging and re-emerging viruses that are dangerous to human health.

Passive antibody therapy, also called serum therapy, is a subtype of passive immunotherapy that administers antibodies to target and kill pathogens or cancer cells. It is designed to draw support from foreign antibodies that are donated from a person, extracted from animals, or made in the laboratory to elicit an immune response instead of relying on the innate immune system to fight disease. It has a long history from the 18th century for treating infectious diseases and is now a common cancer treatment. The mechanism of actions include: antagonistic and agonistic reaction, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).