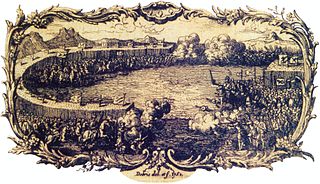

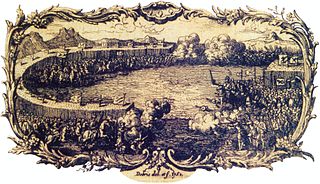

The Battle of Alcácer Quibir was fought in northern Morocco, near the town of Ksar-el-Kebir and Larache, on 4 August 1578.

Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik I, often simply Abd al-Malik or Mulay Abdelmalek, was the Saadian Sultan of Morocco from 1576 until his death right after the Battle of al-Kasr al-Kabir against Portugal in 1578.

Mohammed esh Sheikh el Mamun also spelled Muhammad al-Shaykh al-Ma'mun, among other transliterations; also known as Abu Abdallah Mohammed III, Arabic: أبو العبدالله محمد سعدي الثالث) was a member of the Saadian dynasty who ruled parts of Morocco during the succession conflicts within the dynasty between 1603 and 1627. He was the son of Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur by one of his harem slave concubines named Elkheizourân. He was the full-brother of Abu Faris Abdallah and the half-brother of Zidan Abu Maali.

The Saadi Sultanate, also known as the Sharifian Sultanate, was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of Northwest Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was led by the Saadi dynasty, an Arab Sharifian dynasty.

The Battle of Tondibi was the decisive confrontation in the 16th-century invasion of the Songhai Empire by the army of the Saadi dynasty in Morocco. The Moroccan forces under Judar Pasha defeated the Songhai under Askia Ishaq II, guaranteeing the empire's downfall.

El Badi Palace or Badi' Palace is a ruined palace located in Marrakesh, Morocco. It was commissioned by the sultan Ahmad al-Mansur of the Saadian dynasty a few months after his accession in 1578, with construction and embellishment continuing throughout most of his reign. The palace, decorated with materials imported from numerous countries ranging from Italy to Mali, was used for receptions and designed to showcase the Sultan's wealth and power. It was one part of a larger Saadian palace complex occupying the Kasbah district of Marrakesh.

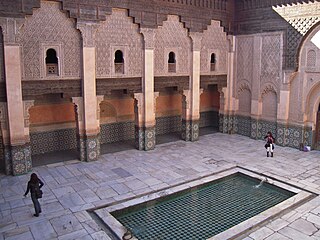

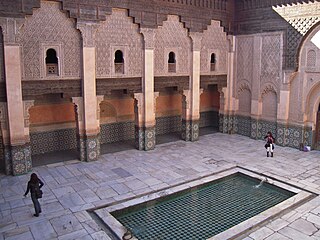

The Saadian Tombs are a historic royal necropolis in Marrakesh, Morocco, located on the south side of the Kasbah Mosque, inside the royal kasbah (citadel) district of the city. They date to the time of the Saadian dynasty and in particular to the reign of Ahmad al-Mansur (1578–1603), though members of Morocco's monarchy continued to be buried here for a time afterwards. The complex is regarded by many art historians as the high point of Moroccan architecture in the Saadian period due to its luxurious decoration and careful interior design. Today the site is a major tourist attraction in Marrakesh.

Abdallah al-Ghalib Billah was the second Saadian sultan of Morocco. He succeeded his father Mohammed al-Shaykh as Sultan of Morocco.

Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Qaim bi-Amr Allah, often shortened to Abu Abdallah al-Qa'im or Muhammad al-Qa'im, was the first political leader of the Saadi Dynasty of Morocco. He ruled the Sous and other parts of southern Morocco from 1510 to 1517, setting the stage for his sons to lead the dynasty to power over the rest of Morocco in the decades after his death.

MawlayMohammed al-Shaykh al-Sharif al-Hassani, known as Mohammed al-Shaykh, was the first sultan of the Saadian dynasty of Morocco (1544–1557). He was particularly successful in expelling the Portuguese from most of their bases in Morocco. He also eliminated the Wattasids and resisted the Ottomans, thereby establishing a complete rule over Morocco.

Zidan Abu Maali was the embattled Saadi Sultan of Morocco from 1603 to 1627. He was the son and heir of Ahmad al-Mansur by his wife Lalla Aisha bint Abu Bakkar, a lady of the Chebanate tribe.

The Capture of Fez occurred in 1576 at the Moroccan city of Fez, when an Ottoman force from Algiers supported the prince Abd al-Malik in gaining the throne of the Saadi Sultanate against his nephew and rival claimant Mulay Muhammed al-Mutawakkil in exchange for making the Sultanate an Ottoman vassal.

Turkey–Morocco relations are the foreign relations between Morocco and Turkey, and spanned a period of several centuries, from the early 16th century when the Ottoman Empire neighbored Morocco and had an expedition there until modern times.

The Pashalik of Timbuktu, also known as the Pashalik of Sudan, was a West African political entity that existed between the 16th and the 19th century. It was formed after the Battle of Tondibi, when a military expedition sent by Saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur of Morocco defeated the Songhai Empire and established control over a territory centered on Timbuktu. Following the decline of the Saadi Sultanate in the early 17th century, Morocco retained only nominal control of the Pashalik.

The Zawiya of Sidi Abd el-Aziz is an Islamic religious complex (zawiya) in Marrakesh, Morocco. It is centered around the tomb of the Muslim scholar and Sufi saint Sidi Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz Abd al-Haq at-Tabba', who died in Marrakesh in 1508. Sidi Abd el-Aziz is considered one of the Seven Saints of Marrakesh, and his tomb was a prominent stop for pilgrims to Marrakesh. The zawiya is located on Rue Mouassine at its intersection with Rue Amesfah.

The Zawiya of Sidi Muhammad Ben Sliman al-Jazuli is an Islamic religious complex (zawiya) in Marrakesh, Morocco. It is centered around the tomb of the 15th-century Muslim scholar and Sufi saint Muhammad al-Jazuli, who is one of the Seven Saints of Marrakesh.

In the 16th century the Ottomans undertook several expeditions to Saadi Sultanate

The Moroccan invasion of the Songhai Empire began with an expedition sent in 1590 by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur of the Saadian dynasty, which ruled over Morocco at the time. The Saadian army, led by Judar Pasha, arrived in the Niger valley region in 1591 and won its first and most decisive victory against the forces of Askia Ishaq II at the Battle of Tondibi and occupied the capital of Gao shortly after.

Sahaba el-Rehmania was the wife of the Moroccan sultan of the Saadian dynasty Mohammed al-Shaykh and the mother of Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik. Gifted in diplomacy, she held a leading political role throughout her life. She was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire at the court of Sultan Murad III.

'Alam al-mansûr or liwa' al-mansûr is a form of flag that was used as the emblem of the Almohad, Marinid, and Saadi dynasties of Morocco consisting of a white banner with an Islamic symbol written on it which were followed in parades by several banners of different colors, most of them red.