Merneferre Ay was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the mid 13th Dynasty. The longest reigning pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty, he ruled a likely fragmented Egypt for over 23 years in the early to mid 17th century BC. A pyramidion bearing his name shows that he possibly completed a pyramid, probably located in the necropolis of Memphis.

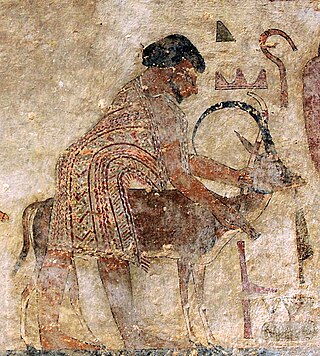

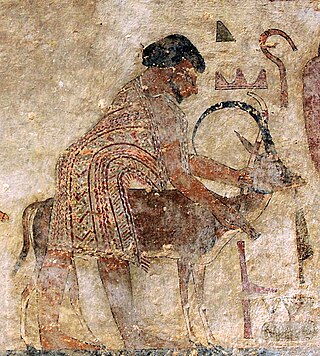

The Hyksos, in modern Egyptology, are the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Their seat of power was the city of Avaris in the Nile Delta, from where they ruled over Lower Egypt and Middle Egypt up to Cusae.

The Second Intermediate Period dates from 1700 to 1550 BC. It marks a period when ancient Egypt was divided into smaller dynasties for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a Second Intermediate Period generally includes the 13th through to the 17th dynasties, however there is no universal agreement in Egyptology about how to define the period.

The Eye of Horus, also known as left wedjat eye or udjat eye, specular to the Eye of Ra, is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. It derives from the mythical conflict between the god Horus with his rival Set, in which Set tore out or destroyed one or both of Horus's eyes and the eye was subsequently healed or returned to Horus with the assistance of another deity, such as Thoth. Horus subsequently offered the eye to his deceased father Osiris, and its revitalizing power sustained Osiris in the afterlife. The Eye of Horus was thus equated with funerary offerings, as well as with all the offerings given to deities in temple ritual. It could also represent other concepts, such as the moon, whose waxing and waning was likened to the injury and restoration of the eye.

Avaris was the Hyksos capital of Egypt located at the modern site of Tell el-Dab'a in the northeastern region of the Nile Delta. As the main course of the Nile migrated eastward, its position at the hub of Egypt's delta emporia made it a major capital suitable for trade. It was occupied from about the 18th century BC until its capture by Ahmose I.

The Early Dynastic Period, also known as Archaic Period or the Thinite Period, is the era of ancient Egypt that immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in c. 3150 BC. It is generally taken to include the First Dynasty and the Second Dynasty, lasting from the end of the archaeological culture of Naqada III until c. 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom. With the First Dynasty, the Egyptian capital moved from Thinis to Memphis, with the unified land being ruled by an Egyptian god-king. In the south, Abydos remained the major centre of ancient Egyptian religion; the hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilization, such as Egyptian art, Egyptian architecture, and many aspects of Egyptian religion, took shape during the Early Dynastic Period.

Meruserre Yaqub-Har was a pharaoh of Egypt during the 17th or 16th century BCE. As he reigned during Egypt's fragmented Second Intermediate Period, it is difficult to date his reign precisely, and even the dynasty to which he belonged is uncertain.

The Thirteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt was a series of rulers from approximately 1803 BC until approximately 1649 BC, i.e. for 154 years. It is often classified as the final dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, but some historians instead group it in the Second Intermediate Period.

The Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt was a series of rulers reigning during the Second Intermediate Period over the Nile Delta region of Egypt. It lasted between 75 and 155 years, depending on the scholar. The capital of the dynasty was Xois in central Delta according to the Egyptian historian Manetho. Kim Ryholt and some historians think it was probably Avaris. The 14th Dynasty was another Egyptian dynasty that existed concurrently with the 13th Dynasty based in Memphis. The Egyptian rulers of the 14th dynasty are recorded and attested in the ancient Egyptian Turin List of Kings. On the other hand, another proposed list of contested vassals or rulers during the 14th Dynasty are identified as being of Canaanite (Semitic) descent, owing to the foreign origins of the names of some of their rulers and princes, like Ipqu, Yakbim, Qareh, or Yaqub-Har. Names in relation with Nubia are also recorded in two cases, king Nehesy and queen Tati. This probably remarks the beginning of Hyksos control and domination over eastern Delta.

Itjtawy or It-Towy, also known by its full name Amenemhat-itjtawy, was an ancient Egyptian royal city established by pharaoh Amenemhat I.

Khasekhemre Neferhotep I was an Egyptian pharaoh of the mid Thirteenth Dynasty ruling in the second half of the 18th century BC during a time referred to as the late Middle Kingdom or early Second Intermediate Period, depending on the scholar. One of the best attested rulers of the 13th Dynasty, Neferhotep I reigned for 11 years.

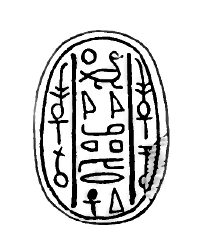

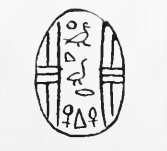

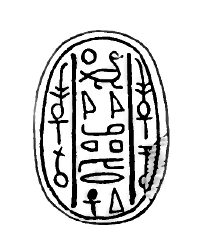

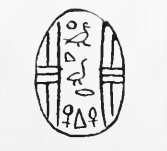

Maaibre Sheshi was a ruler of areas of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. The dynasty, chronological position, duration and extent of his reign are uncertain and subject to ongoing debate. The difficulty of identification is mirrored by problems in determining events from the end of the Middle Kingdom to the arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt. Nonetheless, Sheshi is, in terms of the number of artifacts attributed to him, the best-attested king of the period spanning the end of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate period; roughly from c. 1800 BC until 1550 BC. Hundreds of scaraboid seals bearing his name have been found throughout the Levant, Egypt, Nubia, and as far away as Carthage, where some were still in use 1,500 years after his death.

Sehetepibre Sewesekhtawy was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty during the early Second Intermediate Period, possibly the fifth or tenth king of the Dynasty.

Scarabs are amulets and impression seals shaped according to the eponymous beetles, which were widely popular throughout ancient Egypt. They survive in large numbers today, and through their inscriptions and typology, these artifacts prove to be an important source of information for archaeologists and historians of ancient Egypt, representing a significant body of its art.

Seankhibre Ameny Antef Amenemhat VI was an Egyptian pharaoh of the early Thirteenth Dynasty.

Nehesy Aasehre (Nehesi) was a ruler of Lower Egypt during the fragmented Second Intermediate Period. He is placed by most scholars into the early 14th Dynasty, as either the second or the sixth pharaoh of this dynasty. As such he is considered to have reigned for a short time c. 1705 BC and would have ruled from Avaris over the eastern Nile Delta. Recent evidence makes it possible that a second person with this name, a son of a Hyksos king, lived at a slightly later time during the late 15th Dynasty c. 1580 BC. It is possible that most of the artefacts attributed to the king Nehesy mentioned in the Turin canon, in fact belong to this Hyksos prince.

Qareh Khawoserre was possibly the third king of the Canaanite 14th Dynasty of Egypt, who reigned over the eastern Nile Delta from Avaris during the Second Intermediate Period. His reign is believed to have lasted about 10 years, from 1770 BC until 1760 BC or later, around 1710 BC. Alternatively, Qareh could have been a later vassal of the Hyksos kings of the 15th Dynasty and would then be classified as a king of the 16th Dynasty.

Sewahenre Senebmiu is a poorly attested Egyptian pharaoh during the Second Intermediate Period, thought to belong to the late 13th Dynasty.

Sekhaenre Yakbim or Yakbmu was a ruler during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt. Although his dynastic and temporal collocation is disputed, Danish Egyptologist Kim Ryholt believes that he likely was the founder of the Levantine-blooded Fourteenth Dynasty, while in older literature he was mainly considered a member of the Sixteenth Dynasty.

Nubwoserre Ya'ammu was a ruler during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt. This Asiatic-blooded ruler is traditionally placed in the Sixteenth Dynasty, an hypothesis still in use nowadays by scholars such as Jürgen von Beckerath; although recently Kim Ryholt proposed him as the second ruler of the 14th Dynasty.