The Middle Kingdom of Egypt is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from approximately 2040 to 1782 BC, stretching from the reunification of Egypt under the reign of Mentuhotep II in the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. The kings of the Eleventh Dynasty ruled from Thebes and the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty ruled from el-Lisht.

Thutmose I was the third pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He received the throne after the death of the previous king, Amenhotep I. During his reign, he campaigned deep into the Levant and Nubia, pushing the borders of Egypt farther than ever before in each region. He also built many temples in Egypt, and a tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings; he is the first king confirmed to have done this.

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC, at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom. The dynasty periodically expanded its territory from the Nile delta and valley South beyond the second cataract and East into Canaan.

The Kingdom of Kerma or the Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia", and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt. The polity seems to have been one of a number of Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700 to 1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Sai and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt. Around 1500 BC, it was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. By the eleventh century BC, the more-Egyptianized Kingdom of Kush emerged, possibly from Kerma, and regained the region's independence from Egypt.

The Philae temple complex is an island-based temple complex in the reservoir of the Aswan Low Dam, downstream of the Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser, Egypt.

Khakaure Senusret III was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. He was a great pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty and is considered to rule at the height of the Middle Kingdom. Consequently, he is regarded as one of the sources for the legend about Sesostris. His military campaigns gave rise to an era of peace and economic prosperity that reduced the power of regional rulers and led to a revival in craftwork, trade, and urban development. Senusret III was among the few Egyptian kings who were deified and honored with a cult during their own lifetime.

Khasekhemre Neferhotep I was an Egyptian pharaoh of the mid Thirteenth Dynasty ruling in the second half of the 18th century BC during a time referred to as the late Middle Kingdom or early Second Intermediate Period, depending on the scholar. One of the best attested rulers of the 13th Dynasty, Neferhotep I reigned for 11 years.

Buhen, alternatively known as Βοὥν (Bohón) in Ancient Greek, stands as a significant ancient Egyptian settlement on the western bank of the Nile, just below the Second Cataract in present-day Northern State, Sudan. Its origins trace back to the Old Kingdom period, where it served as an Egyptian colonial town, particularly recognized for copper smelting. In 1962, archaeological discoveries brought to light an ancient copper manufacturing facility encircled by an imposing stone barrier, indicating its origin during the rule of Sneferu in the 4th Dynasty. Inscriptions and graffiti disclosed a continuous Egyptian presence spanning two centuries, only to be interrupted by migration from the southern regions in the 5th Dynasty.

The National Museum of Sudan or Sudan National Museum, abbreviated SNM, is a two-story building, constructed in 1955 and established as national museum in 1971.

The region of Semna is 15 miles south of Wadi Halfa and is situated where rocks cross the Nile narrowing its flow—the Semna Cataract.

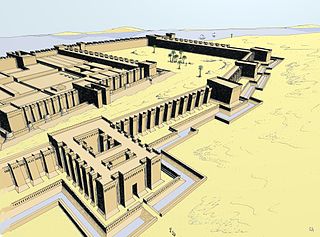

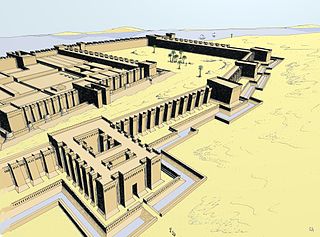

Uronarti, a Nubian word meaning "Island of the King", is an island in the Nile just south of the Second Cataract in the north of Sudan. The primary importance of the island lies in the massive ancient fortress that still stands on its northern end. This fortress is one of a number constructed along the Nile in Lower Nubia during the Middle Kingdom, primarily by the rulers Senusret I and Senusret III.

Nubian architecture is diverse and ancient. Permanent villages have been found in Nubia, which date from 6000 BC. These villages were roughly contemporary with the walled town of Jericho in Palestine.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, or more strictly, Al Dabbah. It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

Ta-Seti was the first nome of Upper Egypt, one of 42 nomoi in Ancient Egypt. Ta-Seti marked the border area towards Nubia, and the name was also used to refer to Nubia itself.

Nehesy Aasehre (Nehesi) was a ruler of Lower Egypt during the fragmented Second Intermediate Period. He is placed by most scholars into the early 14th Dynasty, as either the second or the sixth pharaoh of this dynasty. As such he is considered to have reigned for a short time c. 1705 BC and would have ruled from Avaris over the eastern Nile Delta. Recent evidence makes it possible that a second person with this name, a son of a Hyksos king, lived at a slightly later time during the late 15th Dynasty c. 1580 BC. It is possible that most of the artefacts attributed to the king Nehesy mentioned in the Turin canon, in fact belong to this Hyksos prince.

Tombos or Tumbus is an archaeological site in northern Sudan, including Tombos island and the nearby riverbank area. Tombos is located at the Third Cataract of the Nile and on the northern margin of the Dongola Reach, not far from Kerma. The occupation of Tombos, revealed by archaeological work, began in mid-18th Dynasty of Egypt and continued through the 25th Dynasty. In the New Kingdom period, a large range of pharaonic and private royal inscriptions from 18th Dynasty and elite tombs in Egyptian style indicates Tombos was an important node of Egyptian colonial control. In the New Kingdom, Tombos witnessed the blending and entanglement of Egyptian and Nubian traditions.

Dabenarti is an island in Sudan, situated in the middle of the Nile near the Second Cataract. It is close to Mirgissa, 900 metres (3,000 ft) from its east wall, and about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) south of the Buhen fortress. A fortress on the island was attributed to the Egyptian Nubian period. Construction began during the reign of Senusret I, around 1900 BC, and was completed under Senusret III. Landing at the island fort, measuring 60 by 230 metres in size, was difficult, and it was never completed. With the collapse of Egyptian power at the end of the Middle Kingdom, Dabenarti was abandoned around 1700 BC. It was examined in 1916 by Somers Clarke.

Qakare Ini was an ancient Egyptian or Nubian ruler who most likely reigned at the end of the 11th and beginning of the 12th Dynasty over Lower Nubia. Although he is the best attested Nubian ruler of this time period, nothing is known of his activities.

Shalfak is an ancient Egyptian fortress once built up on the western shore of the Second Cataract of the Nile River and now an island in the Lake Nubia in the north of Sudan. Set up in the Middle Kingdom under Senusret III, it is one of a chain of 17 forts which the pharaohs of the 12th Dynasty established to secure their southern frontier during a time where the Egyptian influence was sought out to be expanded. That is why Shalfak, along with the forts of Buhen, Mirgissa, Uronarti, Askut, Dabenarti, Semna, and Kumma, was established within signalling distance of each other.

The Semna Despatches are a group of papyri that deals with observations of people in and around the forts of the Semna gorge. The fortresses were positioned at Semna because of the expansion of Egypt into Lower Nubia by Senusret III, and were a means of protecting and controlling access into Egypt. The Semna Despatches record the movements of people around the Semna Gorge, and reports their activity's back to an unnamed official in Thebes. Many of the Despatches deal with people who had come to the forts to trade with the Egyptians while others talk about patrols that had gone out and found people in the surrounding desert. The Semna Despatches provides the bulk of information that pertains to the administrative functions of the forts around the Semna Gorge.