The Scottish Colourists were a group of four painters, three from Edinburgh, whose Post-Impressionist work, though not universally recognised initially, came to have a formative influence on contemporary Scottish art and culture. The four artists, Francis Cadell, John Duncan Fergusson, Leslie Hunter and Samuel Peploe, were prolific painters spanning the turn of the twentieth century until the beginnings of World War II. While now banded as one group with a collective achievement and a common sense of British identity, it is a misnomer to believe their artwork or their painterly careers were heterogeneous.

The Scottish Renaissance was a mainly literary movement of the early to mid-20th century that can be seen as the Scottish version of modernism. It is sometimes referred to as the Scottish literary renaissance, although its influence went beyond literature into music, visual arts, and politics. The writers and artists of the Scottish Renaissance displayed a profound interest in both modern philosophy and technology, as well as incorporating folk influences, and a strong concern for the fate of Scotland's declining languages.

The culture of Scotland refers to the patterns of human activity and symbolism associated with Scotland and the Scottish people. The Scottish flag is blue with a white saltire, and represents the cross of Saint Andrew.

The Glasgow School was a circle of influential artists and designers that began to coalesce in Glasgow, Scotland in the 1870s, and flourished from the 1890s to around 1910. Representative groups included The Four, the Glasgow Girls and the Glasgow Boys. Part of the international Art Nouveau movement, they were responsible for creating the distinctive Glasgow Style.

John Duncan Fergusson was a Scottish artist and sculptor, regarded as one of the major artists of the Scottish Colourists school of painting.

Samuel John Peploe was a Scottish Post-Impressionist painter, noted for his still life works and for being one of the group of four painters that became known as the Scottish Colourists. The other colourists were John Duncan Fergusson, Francis Cadell and Leslie Hunter.

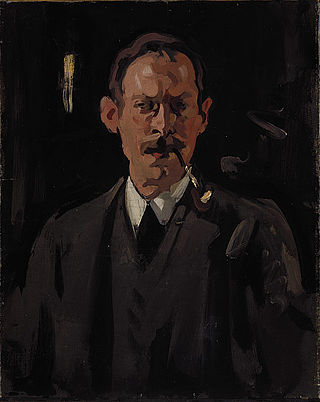

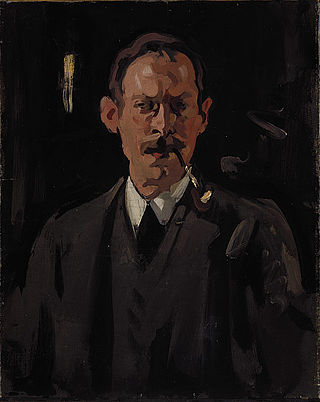

George Leslie Hunter was a Scottish painter, regarded as one of the four artists of the Scottish Colourists group of painters. Christened simply George Hunter, he adopted the name Leslie in San Francisco, and Leslie Hunter became his professional name. Showing an aptitude for drawing at an early age, he was largely self-taught, receiving only elementary painting lessons from a family acquaintance. He spent fourteen years from the age of fifteen in the US, mainly in California. Hunter made an extended trip to Scotland, Paris and New York from 1903 to 1905. In 1906 he left San Francisco and returned to Scotland, painting and drawing there, notably in Fife and at Loch Lomond. Subsequently he travelled widely in Europe, especially in the South of France, but also in the Netherlands, the Pas de Calais and Italy. He also returned to New York in 1924 and 1928–1929.

The Edinburgh School refers to a group of 20th century artists connected with Edinburgh. They share a connection through Edinburgh College of Art, where most studied and worked together during or soon after the First World War. As friends and colleagues, they discussed painting and were influenced by one another's work. They were bound together as members of Edinburgh-based exhibition bodies: the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA), Society of Scottish Artists (SSA) and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour (RSW). They predominantly painted still life and Scottish landscapes, and shared an interest in working both in oil and watercolour.

Scottish art is the body of visual art made in what is now Scotland, or about Scottish subjects, since prehistoric times. It forms a distinctive tradition within European art, but the political union with England has led its partial subsumation in British art.

Hamish MacDonald DA PAI was a Scottish impressionist and colourist artist from Glasgow, Scotland. His paintings feature mainly landscapes and coastal scenes, with some still-life works. His work features in several major collections, including those of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery, the Paisely Art Gallery and that of the Duke of Edinburgh.

Estate houses in Scotland or Scottish country houses, are large houses usually on landed estates in Scotland. They were built from the sixteenth century, after defensive castles began to be replaced by more comfortable residences for royalty, nobility and local lairds. The origins of Scottish estate houses are in aristocratic emulation of the extensive building and rebuilding of royal residences, beginning with Linlithgow, under the influence of Renaissance architecture. In the 1560s the unique Scottish style of the Scots baronial emerged, which combined features from medieval castles, tower houses, and peel towers with Renaissance plans, in houses designed primarily for residence rather than defence.

Scottish art in the nineteenth century is the body of visual art made in Scotland, by Scots, or about Scottish subjects. This period saw the increasing professionalisation and organisation of art in Scotland. Major institutions founded in this period included the Institution for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Scotland, the Royal Scottish Academy of Art, the National Gallery of Scotland, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and the Glasgow Institute. Art education in Edinburgh focused on the Trustees Drawing Academy of Edinburgh. Glasgow School of Art was founded in 1845 and Grays School of Art in Aberdeen in 1885.

The New Scottish Group was a loose collection of artists based in Glasgow, who exhibited from 1942 to 1956. It was formed around John Duncan Fergusson after his return to Glasgow in 1939. It had its origins in the New Art Club formed in 1940, and had its first exhibition in 1942. Members did not have a common style, but shared left-wing views and were influenced by contemporary continental art. Members included Donald Bain, William Crosbie, Marie de Banzie and Isabel Babianska. Tom MacDonald, Bet Low and William Senior formed the Clyde Group to pursue political painting that manifested in urban industrial landscapes. The group helped start the careers of a generation of Glasgow-based artists and was part of a wider cultural "golden age" for the city.

Scottish art in the eighteenth century is the body of visual art made in Scotland, by Scots, or about Scottish subjects, in the eighteenth century. This period saw development of professionalisation, with art academies were established in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Art was increasingly influenced by Neoclassicism, the Enlightenment and towards the end of the century by Romanticism, with Italy becoming a major centre of Scottish art.

Portrait painting in Scotland includes all forms of painted portraiture in Scotland, from its beginnings in the early sixteenth century until the present day. The origins of the tradition of portrait painting in Scotland are in the Renaissance, particularly through contacts with the Netherlands. The first portrait of a named person that survives is that of Archbishop William Elphinstone, probably painted by a Scottish artist using Flemish techniques around 1505. Around the same period Scottish monarchs turned to the recording of royal likenesses in panel portraits, painted in oils on wood. The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was probably disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century. It began to flourish after the Reformation, with paintings of royal figures and nobles by Netherlands artists Hans Eworth, Arnold Bronckorst and Adrian Vanson. A specific type of Scottish picture from this era was the "vendetta portrait", designed to keep alive the memory of an atrocity. The Union of Crowns in 1603 removed a major source of artistic patronage in Scotland as James VI and his court moved to London. The result has been seen as a shift "from crown to castle", as the nobility and local lairds became the major sources of patronage.

Landscape painting in Scotland includes all forms of painting of landscapes in Scotland since its origins in the sixteenth century to the present day. The earliest examples of Scottish landscape painting are in the tradition of Scottish house decoration that arose in the sixteenth century. Often said to be the earliest surviving painted landscape created in Scotland is a depiction by the Flemish artist Alexander Keirincx undertaken for Charles I.

Sculpture in Scotland includes all visual arts operating in three dimensions in the borders of modern Scotland. Durable sculptural processes traditionally include carving and modelling, in stone, metal, clay, wood and other materials. In the modern era these were joined by assembly by welding, modelling, moulding and casting. Some installation art can also be considered to be sculpture. The earliest surviving sculptures from Scotland are standing stones and circles from around 3000 BCE. The oldest portable visual art are carved-stone petrospheres and the Westray Wife is the earliest representation of a human face found in Scotland. From the Bronze Age there are extensive examples of rock art, including cup and ring marks and elaborate carved stone battle-axes. By the early Iron Age Scotland had been penetrated by the wider European La Tène culture, and a few examples of decoration survive from Scotland. There are also decorated torcs, scabbards, armlets and war trumpets. The Romans began military expeditions into what is now Scotland from about 71 CE, leaving a direct sculptural legacy of distance slabs, altars and other sculptures.

Scottish genre art is the depiction of everyday life in Scotland, or by Scottish artists, emulating the genre art of Netherlands painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Common themes included markets, domestic settings, interiors, parties, inn scenes, and street scenes.

Scotland played a major role in the technical development of photography in the nineteenth century through the efforts of figures including James Clerk Maxwell and David Brewster. Its artistic development was pioneered by Robert Adamson and artist David Octavius Hill, whose work is considered to be some of the first and finest artistic uses of photography. Thomas Roger was one of the first commercial photographers. Thomas Keith was one of the first architectural photographers. George Washington Wilson pioneered instant photography and landscape photography. Clementina Hawarden and Mary Jane Matherson were amongst the first female photographers. War photography was pioneered by James MacCosh, James Robertson, Alexander Graham and Mairi Chisholm.