Related Research Articles

Aeschylus was an ancient Greek tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is largely based on inferences made from reading his surviving plays. According to Aristotle, he expanded the number of characters in the theatre and allowed conflict among them. Formerly, characters interacted only with the chorus.

Euripides was a Greek tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him, but the Suda says it was ninety-two at most. Of these, eighteen or nineteen have survived more or less complete. There are many fragments of most of his other plays. More of his plays have survived intact than those of Aeschylus and Sophocles together, partly because his popularity grew as theirs declined—he became, in the Hellenistic Age, a cornerstone of ancient literary education, along with Homer, Demosthenes, and Menander.

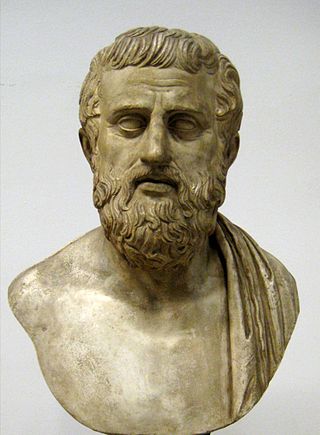

Sophocles was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least one play has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those of Aeschylus and earlier than, or contemporary with, those of Euripides. Sophocles wrote more than 120 plays, but only seven have survived in a complete form: Ajax, Antigone, Women of Trachis, Oedipus Rex, Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus. For almost fifty years, Sophocles was the most celebrated playwright in the dramatic competitions of the city-state of Athens, which took place during the religious festivals of the Lenaea and the Dionysia. He competed in thirty competitions, won twenty-four, and was never judged lower than second place. Aeschylus won thirteen competitions and was sometimes defeated by Sophocles; Euripides won four.

Tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsis, or a "pain [that] awakens pleasure,” for the audience. While many cultures have developed forms that provoke this paradoxical response, the term tragedy often refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of Western civilization. That tradition has been multiple and discontinuous, yet the term has often been used to invoke a powerful effect of cultural identity and historical continuity—"the Greeks and the Elizabethans, in one cultural form; Hellenes and Christians, in a common activity," as Raymond Williams puts it.

The Dionysia was a large festival in ancient Athens in honor of the god Dionysus, the central events of which were the theatrical performances of dramatic tragedies and, from 487 BC, comedies. It was the second-most important festival after the Panathenaia. The Dionysia actually consisted of two related festivals, the Rural Dionysia and the City Dionysia, which took place in different parts of the year. They were also an essential part of the Dionysian Mysteries.

The Frogs is a comedy written by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It was performed at the Lenaia, one of the Festivals of Dionysus in Athens, in 405 BC and received first place.

A theatrical culture flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres emerged there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies. Modern Western theatre comes, in large measure, from the theatre of ancient Greece, from which it borrows technical terminology, classification into genres, and many of its themes, stock characters, and plot elements.

Greek tragedy is one of the three principal theatrical genres from Ancient Greece and Greek inhabited Anatolia, along with comedy and the satyr play. It reached its most significant form in Athens in the 5th century BC, the works of which are sometimes called Attic tragedy.

Pratinas was one of the early tragic poets who flourished at Athens at the beginning of the fifth century BCE, and whose combined efforts were thought by critics to have brought the art to its perfection.

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic period, are the two epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, set in an idealized archaic past today identified as having some relation to the Mycenaean era. These two epics, along with the Homeric Hymns and the two poems of Hesiod, the Theogony and Works and Days, constituted the major foundations of the Greek literary tradition that would continue into the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods.

The satyr play is a form of Attic theatre performance related to both comedy and tragedy. It preserves theatrical elements of dialogue, actors speaking verse, a chorus that dances and sings, masks and costumes. Its relationship to tragedy is strong; satyr plays were written by tragedians, and satyr plays were performed in the Dionysian festival following the performance of a group of three tragedies. The satyr play's mythological-heroic stories and the style of language are similar to that of the tragedies. Its connection with comedy is also significant – it has similar plots, titles, themes, characters, and happy endings. The remarkable feature of the satyr play is the chorus of satyrs, with their costumes that focus on the phallus, and with their language, which uses wordplay, sexual innuendos, references to breasts, farting, erections, and other references that do not occur in tragedy. As Mark Griffith points out, the satyr play was "not merely a deeply traditional Dionysiac ritual, but also generally accepted as the most appropriate and satisfying conclusion to the city’s most complex and prestigious cultural event of the year."

Choerilus was an Athenian tragic poet, who exhibited plays as early as 524 BC.

Phrynichus, son of Polyphradmon and pupil of Thespis, was one of the earliest of the Greek tragedians. Some ancients regarded him as the real founder of tragedy. Phrynichus is said to have died in Sicily. His son Polyphrasmon was also a playwright.

Rush Rehm is professor of drama and classics at Stanford University in California, in the United States. He also works professionally as an actor and director. He has published many works on classical theatre. Rehm is the artistic director of Stanford Repertory Theater (SRT), a professional theater company that presents a dramatic festival based on a major playwright each summer. SRT's 2016 summer festival, Theater Takes a Stand, celebrates the struggle for workers' rights. A political activist, Rehm has been involved in Central American and Cuban solidarity, supporting East Timorese resistance to the Indonesian invasion and occupation, the ongoing struggle for Palestinian rights, and the fight against US militarism. In 2014, he was awarded Stanford's Lloyd W. Dinkelspiel Award for Outstanding Service to Undergraduate Education.

Thessalus was an eminent tragic actor (hypocrites) in the time of Alexander the Great, whose especial favour he enjoyed, and whom he served before his accession to the throne, and afterwards accompanied on his expedition into Asia. He was victor in the Attic Dionysia in 347 and 341, as well as the Lenea. In 340 BC, he acted in the Parthenopaeus of Astydamas.

Athenodorus was a tragic actor, victor at the Dionysia in 342—in the Antigone of Astydamas—and 329 BC. He performed also at the games after the victorious siege of Tyre in honour of Heracles in 331 BC, with the Cypriot Pasicrates of Soli being his choregos, and was victorious over Thessalus, whom Nicocreon of Cyprus supported and Alexander himself favored. Soon afterwards he returned to Athens, as his Dionysiac victory of 329 shows. At some point Athenodorus was fined by the Athenians for failing to appear at the festival, and he asked Alexander to intercede in writing on his behalf; Alexander instead paid his fine. In 324 Athenodorus reappears at the Susa wedding festival, along with Aristocritus and Thessalus.

Philocles, was an Athenian tragic poet during the 5th century BC. Through his mother, Philopatho, he had three famous uncles: Aeschylus, the famous poet, Cynaegirus, hero of the battle of Marathon, and Ameinias, hero of the battle of Salamis. The Suda claims that Philocles was the father of the tragic playwright Morsimus, who was in turn the father of the tragedian Astydamas the Elder and was in his turn the father of the tragedian Astydamas the Younger.

Astydamas was a tragic poet of ancient Greece who lived around the turn of 4th century BCE, from roughly 423 to 363 BCE. He is very often confounded in ancient sources with his more well known and successful son Astydamas the Younger, who was also a tragic poet.

Morsimus or Morsimos was a tragic poet of the 5th century BCE, around 450 to 400 BCE, and the member of a large dynasty of tragic poets. None of his plays survive.

Philocles was a tragic poet of ancient Greece who lived in the 4th century BCE and was a member of a large, multigenerational theatre dynasty.

References

- 1 2 3 Haigh, Arthur Elam (1896). The Tragic Drama of the Greeks. Clarendon Press. p. 429. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Petrides, Antonis K.; Liapis, Vayos, eds. (2019). Greek Tragedy After the Fifth Century: A Survey from Ca. 400 BC to Ca. AD 400. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–10, 15, 26, 30–39, 65, 73, 88, 106, 177, 180–181, 183–185, 202–203, 214, 246–248, 250, 253–254, 273, 276, 281, 332–333. ISBN 9781107038554 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- 1 2 Cropp, Martin, ed. (2019). Minor Greek Tragedians: Fragments from the Tragedies with Selected Testimonia. Vol. 2. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781800348721 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- 1 2 Hanink, Johanna (2014). Lycurgan Athens and the Making of Classical Tragedy. Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9781139993197 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Sommerstein, Alan H. (2013). Aeschylean Tragedy. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9781849667951 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- 1 2 3 Easterling, P.E. (1997). "From repertoire to canon". In Easterling, P.E. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 9780521423519 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- 1 2 Knox, Bernard (1985). "Minor Tragedians". In Knox, Bernard; Easterling, P.E. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Classical Literature. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780521210423 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

The meagre fragments do little to explain his great popularity.

- ↑ Suda s.v. Ἀστυδ

- ↑ Netz, Reviel (2020). Scale, Space and Canon in Ancient Literary Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 554. ISBN 9781108481472 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Manousakis, Nikos (2020). "Aeschylus' Actaeon: A Playboy on the Greek Tragic Stage?". In Lamari, Anna A.; Novokhatko, Anna; Montanari, Franco (eds.). Fragmentation in Ancient Greek Drama. De Gruyter. p. 212. ISBN 9783110621693 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Lycophron (2015). Hornblower, Simon (ed.). Alexandra. Translated by Hornblower, Simon. Oxford University Press. p. 427. ISBN 9780199576708 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Nervegna, Sebastiana (2013). Menander in Antiquity: The Contexts of Reception. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9781107004221 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Anal. 3.329

- ↑ Suda, s.v. Σαυτὴν κ. τ. λ.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 2.43

- ↑ Scodel, Ruth (2007). "Lycurgus and the State Text of Tragedy". In Cooper, Craig Richard (ed.). Politics of Orality. Brill Publishers. pp. 148–149. ISBN 9789004145405 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Page, D.L., ed. (1981). Further Greek Epigrams. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0521229030 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Ma, John (2013). Statues and Cities: Honorific Portraits and Civic Identity in the Hellenistic World. Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780199668915 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Liddel, Peter Philip, ed. (2020). Decrees of Fourth-Century Athens (403/2-322/1 BC). Vol. 1. Translated by Liddel, Peter Philip. Cambridge University Press. p. 774. ISBN 9781316952689 . Retrieved 2024-08-21.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Mason, Charles Peter (1870). "Astydamas". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology . Vol. 1. p. 390.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Mason, Charles Peter (1870). "Astydamas". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology . Vol. 1. p. 390.