In chemistry, a hydrogen bond is primarily an electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bonded to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a lone pair of electrons—the hydrogen bond acceptor (Ac). Such an interacting system is generally denoted Dn−H···Ac, where the solid line denotes a polar covalent bond, and the dotted or dashed line indicates the hydrogen bond. The most frequent donor and acceptor atoms are the period 2 elements nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), and fluorine (F).

An intermolecular force is the force that mediates interaction between molecules, including the electromagnetic forces of attraction or repulsion which act between atoms and other types of neighbouring particles, e.g. atoms or ions. Intermolecular forces are weak relative to intramolecular forces – the forces which hold a molecule together. For example, the covalent bond, involving sharing electron pairs between atoms, is much stronger than the forces present between neighboring molecules. Both sets of forces are essential parts of force fields frequently used in molecular mechanics.

Solvation describes the interaction of a solvent with dissolved molecules. Both ionized and uncharged molecules interact strongly with a solvent, and the strength and nature of this interaction influence many properties of the solute, including solubility, reactivity, and color, as well as influencing the properties of the solvent such as its viscosity and density. If the attractive forces between the solvent and solute particles are greater than the attractive forces holding the solute particles together, the solvent particles pull the solute particles apart and surround them. The surrounded solute particles then move away from the solid solute and out into the solution. Ions are surrounded by a concentric shell of solvent. Solvation is the process of reorganizing solvent and solute molecules into solvation complexes and involves bond formation, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. Solvation of a solute by water is called hydration.

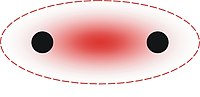

In molecular physics and chemistry, the van der Waals force is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical electronic bond; they are comparatively weak and therefore more susceptible to disturbance. The van der Waals force quickly vanishes at longer distances between interacting molecules.

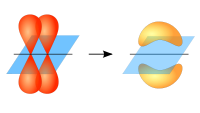

Supramolecular chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry concerning chemical systems composed of a discrete number of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system range from weak intermolecular forces, electrostatic charge, or hydrogen bonding to strong covalent bonding, provided that the electronic coupling strength remains small relative to the energy parameters of the component. While traditional chemistry concentrates on the covalent bond, supramolecular chemistry examines the weaker and reversible non-covalent interactions between molecules. These forces include hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, pi–pi interactions and electrostatic effects.

Relativistic quantum chemistry combines relativistic mechanics with quantum chemistry to calculate elemental properties and structure, especially for the heavier elements of the periodic table. A prominent example is an explanation for the color of gold: due to relativistic effects, it is not silvery like most other metals.

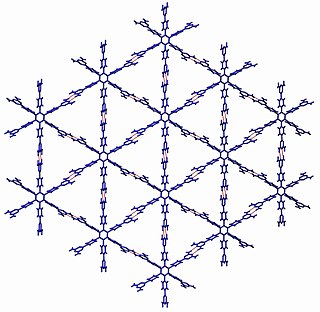

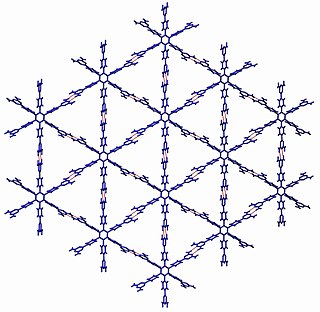

In chemistry, a supramolecular assembly is a structure consisting of molecules held together by noncovalent bonds. While a supramolecular assembly can be simply composed of two molecules, or a defined number of stoichiometrically interacting molecules within a quaternary complex, it is more often used to denote larger complexes composed of indefinite numbers of molecules that form sphere-, rod-, or sheet-like species. Colloids, liquid crystals, biomolecular condensates, micelles, liposomes and biological membranes are examples of supramolecular assemblies, and their realm of study is known as supramolecular chemistry. The dimensions of supramolecular assemblies can range from nanometers to micrometers. Thus they allow access to nanoscale objects using a bottom-up approach in far fewer steps than a single molecule of similar dimensions.

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

In chemistry, a salt bridge is a combination of two non-covalent interactions: hydrogen bonding and ionic bonding. Ion pairing is one of the most important noncovalent forces in chemistry, in biological systems, in different materials and in many applications such as ion pair chromatography. It is a most commonly observed contribution to the stability to the entropically unfavorable folded conformation of proteins. Although non-covalent interactions are known to be relatively weak interactions, small stabilizing interactions can add up to make an important contribution to the overall stability of a conformer. Not only are salt bridges found in proteins, but they can also be found in supramolecular chemistry. The thermodynamics of each are explored through experimental procedures to access the free energy contribution of the salt bridge to the overall free energy of the state.

Crystal engineering studies the design and synthesis of solid-state structures with desired properties through deliberate control of intermolecular interactions. It is an interdisciplinary academic field, bridging solid-state and supramolecular chemistry.

A molecular solid is a solid consisting of discrete molecules. The cohesive forces that bind the molecules together are van der Waals forces, dipole–dipole interactions, quadrupole interactions, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, halogen bonding, London dispersion forces, and in some molecular solids, coulombic interactions. Van der Waals, dipole interactions, quadrupole interactions, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and halogen bonding are typically much weaker than the forces holding together other solids: metallic, ionic, and network solids.

In organometallic chemistry, agostic interaction refers to the intramolecular interaction of a coordinatively-unsaturated transition metal with an appropriately situated C−H bond on one of its ligands. The interaction is the result of two electrons involved in the C−H bond interaction with an empty d-orbital of the transition metal, resulting in a three-center two-electron bond. It is a special case of a C–H sigma complex. Historically, agostic complexes were the first examples of C–H sigma complexes to be observed spectroscopically and crystallographically, due to intramolecular interactions being particularly favorable and more often leading to robust complexes. Many catalytic transformations involving oxidative addition and reductive elimination are proposed to proceed via intermediates featuring agostic interactions. Agostic interactions are observed throughout organometallic chemistry in alkyl, alkylidene, and polyenyl ligands.

In polymer chemistry and materials science, the term "polymer" refers to large molecules whose structure is composed of multiple repeating units. Supramolecular polymers are a new category of polymers that can potentially be used for material applications beyond the limits of conventional polymers. By definition, supramolecular polymers are polymeric arrays of monomeric units that are connected by reversible and highly directional secondary interactions–that is, non-covalent bonds. These non-covalent interactions include van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, Coulomb or ionic interactions, π-π stacking, metal coordination, halogen bonding, chalcogen bonding, and host–guest interaction. The direction and strength of the interactions are precisely tuned so that the array of molecules behaves as a polymer in dilute and concentrated solution, as well as in the bulk.

In chemistry and materials science, molecular self-assembly is the process by which molecules adopt a defined arrangement without guidance or management from an outside source. There are two types of self-assembly: intermolecular and intramolecular. Commonly, the term molecular self-assembly refers to the former, while the latter is more commonly called folding.

In chemistry, a halogen bond occurs when there is evidence of a net attractive interaction between an electrophilic region associated with a halogen atom in a molecular entity and a nucleophilic region in another, or the same, molecular entity. Like a hydrogen bond, the result is not a formal chemical bond, but rather a strong electrostatic attraction. Mathematically, the interaction can be decomposed in two terms: one describing an electrostatic, orbital-mixing charge-transfer and another describing electron-cloud dispersion. Halogen bonds find application in supramolecular chemistry; drug design and biochemistry; crystal engineering and liquid crystals; and organic catalysis.

In chemistry, a metallophilic interaction is defined as a type of non-covalent attraction between heavy metal atoms. The atoms are often within Van der Waals distance of each other and are about as strong as hydrogen bonds. The effect can be intramolecular or intermolecular. Intermolecular metallophilic interactions can lead to formation of supramolecular assemblies whose properties vary with the choice of element and oxidation states of the metal atoms and the attachment of various ligands to them.

Organogold chemistry is the study of compounds containing gold–carbon bonds. They are studied in academic research, but have not received widespread use otherwise. The dominant oxidation states for organogold compounds are I with coordination number 2 and a linear molecular geometry and III with CN = 4 and a square planar molecular geometry.

A two-dimensional polymer (2DP) is a sheet-like monomolecular macromolecule consisting of laterally connected repeat units with end groups along all edges. This recent definition of 2DP is based on Hermann Staudinger's polymer concept from the 1920s. According to this, covalent long chain molecules ("Makromoleküle") do exist and are composed of a sequence of linearly connected repeat units and end groups at both termini.

In chemistry, a chalcogen bond (ChB) is an attractive interaction in the family of σ-hole interactions, along with halogen bonds. Electrostatic, charge-transfer (CT) and dispersion terms have been identified as contributing to this type of interaction. In terms of CT contribution, this family of attractive interactions has been modeled as an electron donor interacting with the σ* orbital of a C-X bond of the bond donor. In terms of electrostatic interactions, the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps is often invoked to visualize the electron density of the donor and an electrophilic region on the acceptor, where the potential is depleted, referred to as a σ-hole. ChBs, much like hydrogen and halogen bonds, have been invoked in various non-covalent interactions, such as protein folding, crystal engineering, self-assembly, catalysis, transport, sensing, templation, and drug design.

In chemistry, sigma hole interactions are a family of intermolecular forces that can occur between several classes of molecules and arise from an energetically stabilizing interaction between a positively-charged site, termed a sigma hole, and a negatively-charged site, typically a lone pair, on different atoms that are not covalently bonded to each other. These interactions are usually rationalized primarily via dispersion, electrostatics, and electron delocalization and are characterized by a strong directional preference that allows control over supramolecular chemistry.