An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. hydrogen ion, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis acid.

A chemical bond is the association of atoms or ions to form molecules, crystals, and other structures. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons as in covalent bonds, or some combination of these effects. Chemical bonds are described as having different strengths: there are "strong bonds" or "primary bonds" such as covalent, ionic and metallic bonds, and "weak bonds" or "secondary bonds" such as dipole–dipole interactions, the London dispersion force, and hydrogen bonding.

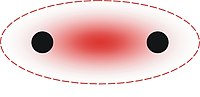

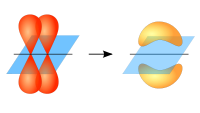

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is known as covalent bonding. For many molecules, the sharing of electrons allows each atom to attain the equivalent of a full valence shell, corresponding to a stable electronic configuration. In organic chemistry, covalent bonding is much more common than ionic bonding.

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an energy change as new products are generated. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking of chemical bonds between atoms, with no change to the nuclei, and can often be described by a chemical equation. Nuclear chemistry is a sub-discipline of chemistry that involves the chemical reactions of unstable and radioactive elements where both electronic and nuclear changes can occur.

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol 2H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, 1H. The deuterium nucleus, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more common 1H has no neutrons. Deuterium has a natural abundance in Earth's oceans of about one atom of deuterium in every 6,420 atoms of hydrogen. Thus deuterium accounts for about 0.0156% by number (0.0312% by mass) of all hydrogen in the ocean: 4.85×1013 tonnes of deuterium – mainly as HOD (or 1HO2H or 1H2HO) and only rarely as D2O (or 2H2O) – in 1.4×1018 tonnes of water. The abundance of 2H changes slightly from one kind of natural water to another (see Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water).

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond is primarily an electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bonded to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a lone pair of electrons—the hydrogen bond acceptor (Ac). Such an interacting system is generally denoted Dn−H···Ac, where the solid line denotes a polar covalent bond, and the dotted or dashed line indicates the hydrogen bond. The most frequent donor and acceptor atoms are the period 2 elements nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), and fluorine (F).

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and biochemistry, the distinction from ions is dropped and molecule is often used when referring to polyatomic ions.

Metallic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that arises from the electrostatic attractive force between conduction electrons and positively charged metal ions. It may be described as the sharing of free electrons among a structure of positively charged ions (cations). Metallic bonding accounts for many physical properties of metals, such as strength, ductility, thermal and electrical resistivity and conductivity, opacity, and lustre.

In chemistry, there are three definitions in common use of the word "base": Arrhenius bases, Brønsted bases, and Lewis bases. All definitions agree that bases are substances that react with acids, as originally proposed by G.-F. Rouelle in the mid-18th century.

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen (H−), a hydrogen atom with two electrons. The term is applied loosely. At one extreme, all compounds containing covalently bound H atoms are also called hydrides: water (H2O) is a hydride of oxygen, ammonia is a hydride of nitrogen, etc. For inorganic chemists, hydrides refer to compounds and ions in which hydrogen is covalently attached to a less electronegative element. In such cases, the H centre has nucleophilic character, which contrasts with the protic character of acids. The hydride anion is very rarely observed.

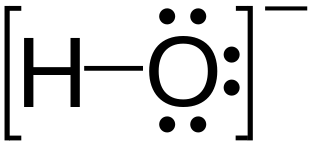

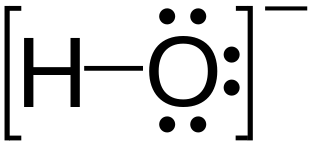

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bond and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone pairs are found in the outermost electron shell of atoms. They can be identified by using a Lewis structure. Electron pairs are therefore considered lone pairs if two electrons are paired but are not used in chemical bonding. Thus, the number of electrons in lone pairs plus the number of electrons in bonds equals the number of valence electrons around an atom.

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carries a partial positive charge, or have an atom that does not have an octet of electrons.

A hydrogen ion is created when a hydrogen atom loses an electron. A positively charged hydrogen ion (or proton) can readily combine with other particles and therefore is only seen isolated when it is in a gaseous state or a nearly particle-free space. Due to its extremely high charge density of approximately 2×1010 times that of a sodium ion, the bare hydrogen ion cannot exist freely in solution as it readily hydrates, i.e., bonds quickly. The hydrogen ion is recommended by IUPAC as a general term for all ions of hydrogen and its isotopes. Depending on the charge of the ion, two different classes can be distinguished: positively charged ions and negatively charged ions.

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

A molecular solid is a solid consisting of discrete molecules. The cohesive forces that bind the molecules together are van der Waals forces, dipole–dipole interactions, quadrupole interactions, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, halogen bonding, London dispersion forces, and in some molecular solids, coulombic interactions. Van der Waals, dipole interactions, quadrupole interactions, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and halogen bonding are typically much weaker than the forces holding together other solids: metallic, ionic, and network solids.

This glossary of chemistry terms is a list of terms and definitions relevant to chemistry, including chemical laws, diagrams and formulae, laboratory tools, glassware, and equipment. Chemistry is a physical science concerned with the composition, structure, and properties of matter, as well as the changes it undergoes during chemical reactions; it features an extensive vocabulary and a significant amount of jargon.

Water is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "universal solvent" and the "solvent of life". It is the most abundant substance on the surface of Earth and the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas on Earth's surface. It is also the third most abundant molecule in the universe.

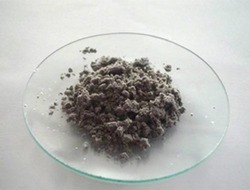

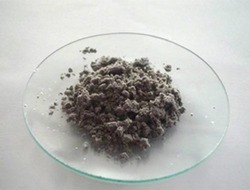

Iron(II) hydride, systematically named iron dihydride and poly(dihydridoiron) is solid inorganic compound with the chemical formula (FeH

2)

n (also written ([FeH

2])n or FeH

2). ). It is kinetically unstable at ambient temperature, and as such, little is known about its bulk properties. However, it is known as a black, amorphous powder, which was synthesised for the first time in 2014.

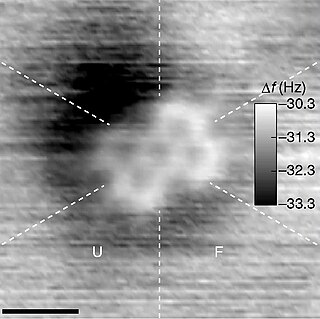

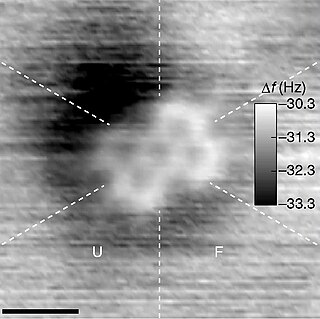

Proton tunneling is a type of quantum tunneling involving the instantaneous disappearance of a proton in one site and the appearance of the same proton at an adjacent site separated by a potential barrier. The two available sites are bounded by a double well potential of which its shape, width and height are determined by a set of boundary conditions. According to the WKB approximation, the probability for a particle to tunnel is inversely proportional to its mass and the width of the potential barrier. Electron tunneling is well-known. A proton is about 2000 times more massive than an electron, so it has a much lower probability of tunneling; nevertheless, proton tunneling still occurs especially at low temperatures and high pressures where the width of the potential barrier is decreased.

Hydrogen-bridged cations are a type of charged species in which a hydrogen atom is simultaneously bonded to two atoms through partial sigma bonds. While best observable in the presence of superacids at room temperature, spectroscopic evidence has suggested that hydrogen-bridged cations exist in ordinary solvents. These ions have been the subject of debate as they constitute a type of charged species of uncertain electronic structure.