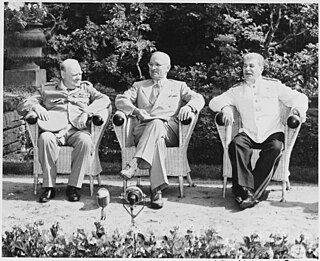

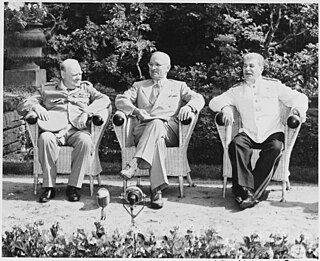

The Potsdam Conference was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They were represented respectively by General Secretary Joseph Stalin, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, and President Harry S. Truman. They gathered to decide how to administer Germany, which had agreed to an unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier. The goals of the conference also included establishing the postwar order, solving issues on the peace treaty, and countering the effects of the war.

United States nationality law details the conditions in which a person holds United States nationality. In the United States, nationality is typically obtained through provisions in the U.S. Constitution, various laws, and international agreements. Citizenship is a right, not a privilege. While domestic documents often use citizenship and nationality interchangeably, nationality refers to the legal means in which a person obtains a national identity and formal membership in a nation and citizenship refers to the relationship held by nationals who are also citizens.

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation are separated from the relationship between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Some nations domestically use the terms interchangeably, though by the 20th century, nationality had commonly come to mean the status of belonging to a particular nation with no regard to the type of governance which established a relationship between the nation and its people. In law, nationality describes the relationship of a national to the state under international law and citizenship describes the relationship of a citizen within the state under domestic statutes. Different regulatory agencies monitor legal compliance for nationality and citizenship. A person in a country of which he or she is not a national is generally regarded by that country as a foreigner or alien. A person who has no recognised nationality to any jurisdiction is regarded as stateless.

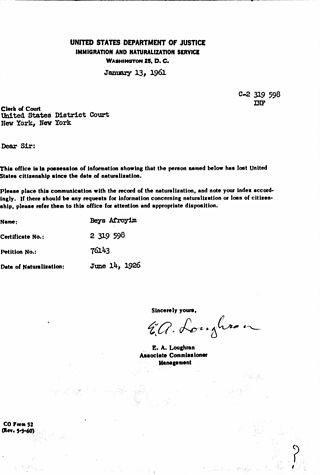

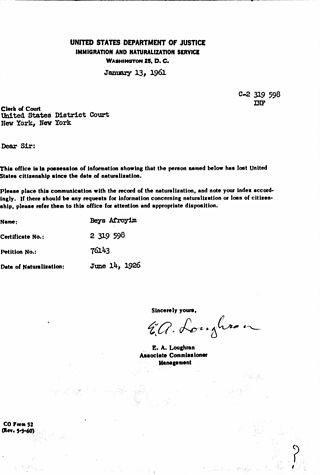

Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled that citizens of the United States may not be deprived of their citizenship involuntarily. The U.S. government had attempted to revoke the citizenship of Beys Afroyim, a man born in Poland, because he had cast a vote in an Israeli election after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen. The Supreme Court decided that Afroyim's right to retain his citizenship was guaranteed by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In so doing, the Court struck down a federal law mandating loss of U.S. citizenship for voting in a foreign election—thereby overruling one of its own precedents, Perez v. Brownell (1958), in which it had upheld loss of citizenship under similar circumstances less than a decade earlier.

Brazilian nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Brazil. The primary law governing nationality requirements is the 1988 Constitution of Brazil, which came into force on 5 October 1988.

Moroccan nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Morocco, as amended; the Moroccan Nationality Code, and its revisions; the Mudawana (Family Code; the Civil Liberties Code; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Morocco. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Moroccan nationality is typically obtained under the jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Morocco or abroad to parents with Moroccan nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established that a United States citizen cannot have their citizenship taken away unless they have acted with an intent to give up that citizenship. The Supreme Court overturned portions of an act of Congress which had listed various actions and had said that the performance of any of these actions could be taken as conclusive, irrebuttable proof of intent to give up U.S. citizenship. However, the Court ruled that a person's intent to give up citizenship could be established through a standard of preponderance of evidence — rejecting an argument that intent to relinquish citizenship could only be found on the basis of clear, convincing and unequivocal evidence.

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constitution and laws of the United States, such as freedom of expression, due process, the rights to vote, live and work in the United States, and to receive federal assistance.

Multiple citizenship is a person's legal status in which a person is at the one time recognized by more than one country under its nationality and citizenship law as a national or citizen of that country. There is no international convention which determines the nationality or citizenship status of a person, which is consequently determined exclusively under national laws, that often conflict with each other, thus allowing for multiple citizenship situations to arise.

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce between His Majesty the Magnificent King of Siam and the United States of America, or Roberts Treaty of 1833, was the first treaty between the United States and an Asian nation.

The Expatriation Act of 1868 was an act of the 40th United States Congress that declared, as part of the United States nationality law, that the right of expatriation is "a natural and inherent right of all people" and "that any declaration, instruction, opinion, order, or decision of any officers of this government which restricts, impairs, or questions the right of expatriation, is hereby declared inconsistent with the fundamental principles of this government".

The Nationality Act of 1940 revised numerous provisions of law relating to American citizenship and naturalization. It was enacted by the 76th Congress of the United States and signed into law on October 14, 1940, a year after World War II had begun in Europe, but before the U.S. entered the war.

Peter John Spiro is an American legal scholar whose specialities include international law and U.S. constitutional law. He is a leading expert on dual citizenship. Formerly the Rusk Professor of International Law at the University of Georgia, since 2006 he has been the Charles R. Weiner Professor of Law at Temple University.

Under United States federal law, a U.S. citizen or national may voluntarily and intentionally give up that status and become an alien with respect to the United States. Relinquishment is distinct from denaturalization, which in U.S. law refers solely to cancellation of illegally procured naturalization.

Guam is an island in the Marianas archipelago of the Northern Pacific located between Japan and New Guinea on a north–south axis and Hawaii and the Philippines on an east–west axis. Inhabitants were Spanish nationals from 1521 until the Spanish–American War of 1898, from which point they derived their nationality from United States law. Nationality is the legal means in which inhabitants acquire formal membership in a nation without regard to its governance type. In addition to being United States nationals, people born in Guam are both citizens of the United States and citizens of Guam. Citizenship is the relationship between the government and the governed, the rights and obligations that each owes the other, once one has become a member of a nation. Though the Constitution of the United States recognizes both national and state citizenship as a means of accessing rights, Guam's history as a territory has created both confusion over the status of its nationals and citizenship and controversy because of distinctions between jurisdictions of the United States.

Relations between the Free Cities of Bremen, Lübeck, and Hamburg and the United States date back to 1790s when Hamburg became the first of the republics to recognized the U.S. on June 17, 1790. Bremen followed suit on March 28, 1794. Diplomatic relations were formally established in October 1853 when the U.S. received Rudolph Schleiden as Minister Resident of the Hanseatic Legation in Washington, D.C. Relations ended in 1868 as the republics would join North German Confederation.

The Grand Duchy of Hesse and the United States began relations in 1829 with mutual recognition going through expansion in 1868 when the Duchy joined the German Empire in 1871. Relations would eventually end with World War I when the U.S. declared war on Germany.

After the Austro-Prussian War the North German Confederation was established in 1866 with the United States recognizing the Confederation in 1867. Formal diplomatic relations were never established. Four years later the Confederation later merged with the German Empire where relations continued.

The Kingdom of Württemberg and the United States began relations in 1825 when both countries mutually recognized each other. Relations continued when Württemberg joined the German Empire in 1871. Relations would eventually end with World War I when the U.S. declared war on Germany.