Alma Woodsey Thomas was an African-American artist and teacher who lived and worked in Washington, D.C., and is now recognized as a major American painter of the 20th century. Thomas is best known for the "exuberant", colorful, abstract paintings that she created after her retirement from a 35-year career teaching art at Washington's Shaw Junior High School.

Yvonne Helene Jacquette was an American painter, printmaker, and educator. She was known in particular for her depictions of aerial landscapes, especially her low-altitude and oblique aerial views of cities or towns, often painted using a distinctive, pointillistic technique. Through her marriage with Rudy Burckhardt, she was a member of the Burckhardt family by marriage. Her son is Tom Burckhardt.

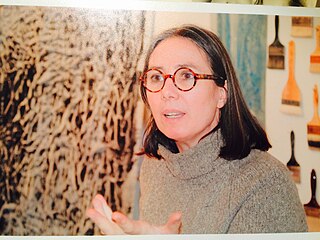

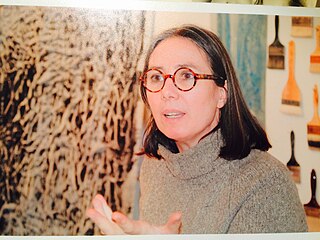

Susan Charna Rothenberg was an American contemporary painter, printmaker, sculptor, and draughtswoman. She became known as an artist through her iconic images of the horse, which synthesized the opposing forces of abstraction and representation.

Rosalyn Drexler is an American visual artist, novelist, Obie Award-winning playwright, and Emmy Award-winning screenwriter, and former professional wrestler. Although she has had a polymathic career, Drexler is perhaps best known for her pop art paintings and as the author of the novelization of the film Rocky, under the pseudonym Julia Sorel. Drexler currently lives and works in New York City, New York.

Squeak Carnwath is an American contemporary painter and arts educator. She is a professor emerita of art at the University of California, Berkeley. She has a studio in Oakland, California, where she has lived and worked since 1970.

Janet Fish is a contemporary American realist artist. Through oil painting, lithography, and screenprinting, she explores the interaction of light with everyday objects in the still life genre. Many of her paintings include elements of transparency, reflected light, and multiple overlapping patterns depicted in bold, high color values. She has been credited with revitalizing the still life genre.

Stephen Westfall is an American painter, critic, and professor at Rutgers University and Bard College.

Katherine Bradford, née Houston, is an American artist based in New York City, known for figurative paintings, particularly of swimmers, that critics describe as simultaneously representational, abstract and metaphorical. She began her art career relatively late and has received her widest recognition in her seventies. Critic John Yau characterizes her work as independent of canon or genre dictates, open-ended in terms of process, and quirky in its humor and interior logic.

Joyce Kozloff is an American artist known for her paintings, murals, and public art installations. She was one of the original members of the Pattern and Decoration movement and an early artist in the 1970s feminist art movement, including as a founding member of the Heresies collective.

Valerie Jaudon is an American painter commonly associated with various Postminimal practices – the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, site-specific public art, and new tendencies in abstraction.

Polly E. Apfelbaum is an American contemporary visual artist, who is primarily known for her colorful drawings, sculptures, and fabric floor pieces, which she refers to as "fallen paintings". She currently lives and works in New York City, New York.

Leslie Wayne is a visual artist who lives and works in New York. Wayne is best known for her "highly dimensional paintings".

Brenda Goodman is an artist and painter currently living and working in Pine Hill, New York. Her artistic practice includes paintings, works on paper, and sculptures.

Vicky Colombet is a French-born American visual Artist. She lives in New York and Paris.

Barbara Grad is an American artist and educator, known for abstract, fractured landscape paintings, which combine organic and geometric forms, colliding planes and patterns, and multiple perspectives. Her work's themes include the instability of experience, the ephemerality of nature, and the complexity of navigating cultural environments in flux. While best known as a painter, Grad also produces drawings, prints, mixed-media works and artist books. She has exhibited in venues including the Art Institute of Chicago, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Danforth Art, Rose Art Museum, Indianapolis Museum of Art and A.I.R., and been reviewed in publications, including Artforum, Arts Magazine and ARTnews. Grad co-founded Artemisia Gallery, one the country's first women-artist collectives, in Chicago in 1973. She has been an educator for over four decades, most notably at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Grad has been based in the Boston area since 1987.

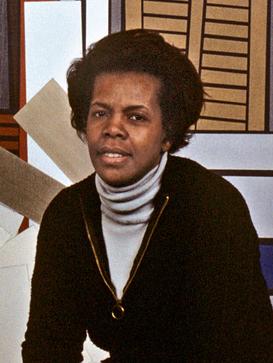

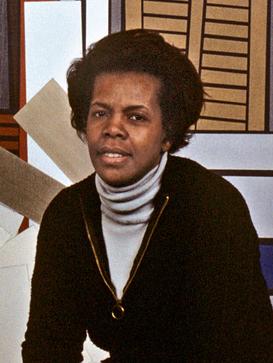

Mavis Iona Pusey was a Jamaican-born American abstract artist. She was a printmaker and painter who was well known for her hard-edge, nonrepresentational images. Pusey drew inspirations from urban construction. She was a leading abstractionist and made works inspired by the constantly changing landscape.

Joanna Pousette-Dart is an American abstract artist, based in New York City. She is best known for her distinctive shaped-canvas paintings, which typically consist of two or three stacked, curved-edge planes whose arrangements—from slightly precarious to nested—convey a sense of momentary balance with the potential to rock, tilt or slip. She overlays the planes with meandering, variable arabesque lines that delineate interior shapes and contours, often echoing the curves of the supports. Her work draws on diverse inspirations, including the landscapes of the American Southwest, Islamic, Mozarabic and Catalan art, Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy, and Mayan art, as well as early and mid-20th-century modernism. Critic John Yau writes that her shaped canvasses explore "the meeting place between abstraction and landscape, quietly expanding on the work of predecessors", through a combination of personal geometry and linear structure that creates "a sense of constant and latent movement."

Judy Ledgerwood is an American abstract painter and educator, who has been based in Chicago. Her work confronts fundamental, historical and contemporary issues in abstract painting within a largely high-modernist vocabulary that she often complicates and subverts. Ledgerwood stages traditionally feminine-coded elements—cosmetic and décor-related colors, references to ornamental and craft traditions—on a scale associated with so-called "heroic" abstraction; critics suggest her work enacts an upending or "domestication" of modernist male authority that opens the tradition to allusions to female sexuality, design, glamour and pop culture. Critic John Yau writes, "In Ledgerwood’s paintings the viewer encounters elements of humor, instances of surprise, celebrations of female sexuality, forms of vulgar tactility, and intense and unpredictable combinations of color. There is nothing formulaic about her approach."

Harriet Korman is an American abstract painter based in New York City, who first gained attention in the early 1970s. She is known for work that embraces improvisation and experimentation within a framework of self-imposed limitations that include simplicity of means, purity of color, and a strict rejection of allusion, illusion, naturalistic light and space, or other translations of reality. Writer John Yau describes Korman as "a pure abstract artist, one who doesn’t rely on a visual hook, cultural association, or anything that smacks of essentialization or the spiritual," a position he suggests few post-Warhol painters have taken. While Korman's work may suggest early twentieth-century abstraction, critics such as Roberta Smith locate its roots among a cohort of early-1970s women artists who sought to reinvent painting using strategies from Process Art, then most associated with sculpture, installation art and performance. Since the 1990s, critics and curators have championed this early work as unjustifiably neglected by a male-dominated 1970s art market and deserving of rediscovery.

Jaq Chartier is an American visual artist. Chartier gained recognition for her Testing series, abstract paintings that are also active visual records of Chartier's tests of her materials - how they migrate and change in reaction to each other, sunlight, and the passage of time.