Related Research Articles

America's Stonehenge is a privately owned tourist attraction and archaeological site consisting of a number of large rocks and stone structures scattered around roughly 30 acres within the town of Salem, New Hampshire, in the United States. It is open to the public for a fee as part of a recreational area which includes snowshoe trails and an alpaca farm.

Pseudoarchaeology consists of attempts to study, interpret, or teach about the subject-matter of archaeology while rejecting, ignoring, or misunderstanding the accepted data-gathering and analytical methods of the discipline. These pseudoscientific interpretations involve the use of artifacts, sites or materials to construct scientifically insubstantial theories to strengthen the pseudoarchaeologists' claims. Methods include exaggeration of evidence, dramatic or romanticized conclusions, use of fallacious arguments, and fabrication of evidence.

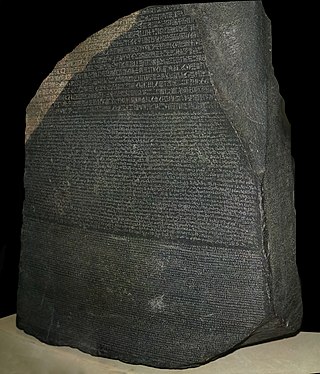

Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the writing and the writers. Specifically excluded from epigraphy are the historical significance of an epigraph as a document and the artistic value of a literary composition. A person using the methods of epigraphy is called an epigrapher or epigraphist. For example, the Behistun inscription is an official document of the Achaemenid Empire engraved on native rock at a location in Iran. Epigraphists are responsible for reconstructing, translating, and dating the trilingual inscription and finding any relevant circumstances. It is the work of historians, however, to determine and interpret the events recorded by the inscription as document. Often, epigraphy and history are competences practised by the same person. Epigraphy is a primary tool of archaeology when dealing with literate cultures. The US Library of Congress classifies epigraphy as one of the auxiliary sciences of history. Epigraphy also helps identify a forgery: epigraphic evidence formed part of the discussion concerning the James Ossuary.

The Los Lunas Decalogue Stone is a hoax associated with a large boulder on the side of Hidden Mountain, near Los Lunas, New Mexico, about 35 miles (56 km) south of Albuquerque, that bears a nine-line inscription carved into a flat panel. The stone is also known as the Los Lunas Mystery Stone or Commandment Rock. The stone has gained notoriety in that some claim the inscription is Pre-Columbian, and therefore proof of early Semitic contact with the Americas. Standard archeological evidence contradicts this, however.

The Jiroft culture, also known as the Intercultural style or the Halilrud style, is an early Bronze Age archaeological culture, located in the territory of present-day Sistan and Baluchestan and Kermān Provinces of Iran.

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. They are often called hieroglyphs due to the iconic shapes of many of the glyphs, a pattern superficially similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Fifteen distinct writing systems have been identified in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, many from a single inscription. The limits of archaeological dating methods make it difficult to establish which was the earliest and hence the progenitor from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Earlier scripts with poorer and varying levels of decipherment include the Olmec hieroglyphs, the Zapotec script, and the Isthmian script, all of which date back to the 1st millennium BC. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved, partly in indigenous scripts and partly in postconquest transcriptions in the Latin script.

David Humiston Kelley was an American archaeologist and epigrapher. He was associated with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and later with the University of Calgary. He is most noted for his work on the phonetic analysis and major contributions toward the decipherment of the writing system used by the Maya civilization of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, the Maya script.

Senarath Paranavitana, was a Sri Lankan archeologist and epigraphist, who pioneered much of post-colonial archaeology in Sri Lanka. He served as the Commissioner of Archeology from 1940 to 1956 and there after as Professor of Archeology at the University of Ceylon from 1957 to 1961.

Stephen Douglas Houston is an American anthropologist, archaeologist, epigrapher, and Mayanist scholar, who is particularly renowned for his research into the pre-Columbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica. He is the author of a number of papers and books concerning topics such as the Maya script, the history, kingships and dynastic politics of the pre-Columbian Maya, and archaeological reports on several Maya archaeological sites, particularly Dos Pilas and El Zotz. In 2021, National Geographic noted that he participated in the correct cultural association assigned to a half-size replica discovered at the Tikal site of the six-story pyramid of the mighty Teotihuacan culture, which replicated its Citadel that includes the original Feathered Serpent Pyramid.

David S. Stuart is an archaeologist and epigrapher specializing in the study of ancient Mesoamerica, the area now called Mexico and Central America. His work has studied many aspects of the ancient Maya civilization. He is widely recognized for his breakthroughs in deciphering Maya hieroglyphs and interpreting Maya art and iconography, starting at an early age. He is the youngest person ever to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, at age 18. He currently teaches at the University of Texas at Austin and his current research focuses on the understanding of Maya culture, religion and history through their visual culture and writing system.

Iravatham Mahadevan was an Indian epigraphist and civil servant, known for his decipherment of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions and for his expertise on the epigraphy of the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Bat Creek inscription is an inscribed stone tablet found by John W. Emmert on February 14, 1889. Emmert claimed to have found the tablet in Tipton Mound 3 during an excavation of Hopewell mounds in Loudon County, Tennessee. This excavation was part of a larger series of excavations that aimed to clarify the controversy regarding who is responsible for building the various mounds found in the Eastern United States.

Simon Martin is a British epigrapher, historian, writer and Mayanist scholar. He is best known for his contributions to the study and decipherment of the Maya script, the writing system used by the pre-Columbian Maya civilisation of Mesoamerica. As one of the leading epigraphers active in contemporary Mayanist research, Martin has specialised in the study of the political interactions and dynastic histories of Classic-era Maya polities. Since 2003 Martin has held positions at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology where he is currently an Associate Curator and Keeper in the American Section, while teaching select courses as an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Terence Bruce Mitford FBA FSA was a Scottish archaeologist and classicist. He spent his whole career at the University of St Andrews, and had a special interest in the history and archaeology of Cyprus and southern Turkey, making many expeditions to these areas. His academic life was interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served with the Special Air Service and Special Boat Service.

Stephen Williams was an archaeologist at Harvard University who held the title of Peabody Professor of North American Archaeology and Ethnography.

Margherita Guarducci, also spelled Guarduci, was an Italian archaeologist, classical scholar, and epigrapher. She was a major figure in several crucial moments of the 20th-century academic community. A student of Federico Halbherr, she edited his works after his death. She was the first woman to lead archaeological excavations at the Vatican, succeeding Ludwig Kaas, and completed the excavations on Saint Peter's tomb, identifying finds as relics of Saint Peter. She has also engaged in discussions on the authenticity of the Praeneste fibula, arguing that its inscription is a forgery.

Dr. Koluvail Vyasaraya Ramesh was an Indian epigraphist and Sanskrit scholar who served as the Chief Epigraphist and Joint Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Mangulam or Mankulam is a village in Madurai district, Tamil Nadu, India. It is located 25 kilometres (16 mi) from Madurai. The inscriptions discovered in the region are the earliest Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions.

America B.C.: Ancient Settlers in the New World is a 1976 book written by Barry Fell that tries to establish that North America was visited by many different European Bronze Age cultures long before either Leif Ericsson or Christopher Columbus.

Sterling Dow was an American classical archaeologist, epigrapher, and professor of archaeology at Harvard University.

References

Notes

- ↑ Fell, Barry (1941). Direct development in the ophiuroidea, and its causes (PhD). University of Edinburgh.

- ↑ Fell, H.B., Clark, H.E.S. 1959. Anareaster, a new genus of Asteroidea from Antarctica. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 87(1–2): 185–187.

- ↑ Brockie 2009.

- ↑ "The Case of Barry Fell". The Atlantic . Washington, DC. January 2000. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ↑ Fell, Barry (1976). America B.C. : ancient settlers in the New World. Internet Archive. New York : Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co. ISBN 978-0-8129-0624-0.

- ↑ Williams, Stephen (1991). Fantastic Archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 264–273. ISBN 0-8122-8238-8.

- ↑ Feder, Kenneth L. (1996). Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. Mountain View: Mayfield. pp. 101–107. ISBN 1-55934-523-3.

- ↑ Such statements were made in several articles published by The West Virginia Archeologist

- ↑ Goddard, Ives; Fitzhugh, William W. (September 1978). "Barry Fell Reexamined". The Biblical Archaeologist . 41 (3): 85–88. doi:10.2307/3209452. JSTOR 3209452. S2CID 166199331.

- ↑ Fell, Barry (1983). "Christian Messages in Old Irish Script Deciphered from Rock Carvings in W. Va". Wonderful West Virginia. 47 (1): 12–19. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2014– via Council for West Virginia Archaeology.

- ↑ Lesser, W. Hunter (1983). "Cult Archaeology Strikes Again: A Case for Pre-Columbian Irishmen in the Mountain State?". The West Virginia Archeologist. 35 (2). Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014– via Council for West Virginia Archaeology.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Monroe; Wirtz, Willard (1989). "A Linguistic Analysis of Some West Virginia Petroglyphs". The West Virginia Archeologist. 41 (1). Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2014– via Council for West Virginia Archaeology.

- ↑ Kelley, D. H. (Spring 1990). "Proto-Tifinagh and Proto-Ogham in the Americas: Review of Fell; Fell and Farley; Fell and Reinert; Johannessen, et al.; McGlone and Leonard; Totten". The Review of Archaeology. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ↑ Feder, Kenneth L. (1984). "Irrationality and Popular Archaeology" (PDF). American Antiquity. 49 (3): 525–541. doi:10.2307/280358. JSTOR 280358. S2CID 163298820. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

Bibliography

- Brockie, Bob (7 December 2009). "Kiwi cult figure a genius or away with the fairies?". Dominion Post . Wellington. p. B5.