Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and 14th centuries.

The Battle of Bannockburn was fought on 23–24 June 1314, between the army of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, and the army of King Edward II of England, during the First War of Scottish Independence. It was a decisive victory for Robert Bruce and formed a major turning point in the war, which ended 14 years later with the de jure restoration of Scottish independence under the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton. For this reason, the Battle of Bannockburn is widely considered a landmark moment in Scottish history.

The Battle of Halidon Hill took place on 19 July 1333 when a Scottish army under Sir Archibald Douglas attacked an English army commanded by King Edward III of England and was heavily defeated. The year before, Edward Balliol had seized the Scottish Crown from five-year-old David II, surreptitiously supported by Edward III. This marked the start of the Second War of Scottish Independence. Balliol was shortly expelled from Scotland by a popular uprising, which Edward III used as a casus belli, invading Scotland in 1333. The immediate target was the strategically-important border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, which the English besieged in March.

The Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of King David II of Scotland, the son of King Robert Bruce, and English-backed invaders supporting Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland, on 11 August 1332. It took place a little to the south-west of Perth, Scotland, when a Scottish force commanded by Donald, Earl of Mar, estimated to have been stronger than 15,000 and possibly as many as 40,000 men, attacked a largely English force of 1,500 commanded by Balliol and Henry Beaumont, Earl of Buchan. This was the first major battle of the Second War of Scottish Independence.

Andrew Moray, also known as Andrew de Moray, Andrew of Moray, or Andrew Murray, was a Scots esquire. He rose to prominence during the First Scottish War of Independence, initially raising a small band of supporters at Avoch Castle in early summer 1297 to fight King Edward I of England. He soon had successfully regained control of the north for the absent Scots king, John Balliol. Moray subsequently merged his army with that of William Wallace, and jointly led the combined army to victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge on 11 September 1297. He was severely wounded in that battle, dying at an unknown date and place that year.

Patrick de Dunbar, 9th Earl of March, was a prominent Scottish magnate during the reigns of Robert the Bruce and David II.

Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray was a soldier and diplomat in the Wars of Scottish Independence, who later served as regent of Scotland. He was a nephew of Robert the Bruce, who created him as the first earl of Moray. He was known for successfully capturing Edinburgh Castle from the English, and he was one of the signatories of the Declaration of Arbroath.

The First War of Scottish Independence was the first of a series of wars between English and Scottish forces. It lasted from the English invasion of Scotland in 1296 until the de jure restoration of Scottish independence with the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328. De facto independence was established in 1314 at the Battle of Bannockburn. The wars were caused by the attempts of the English kings to establish their authority over Scotland while Scots fought to keep English rule and authority out of Scotland.

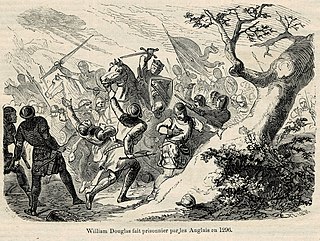

Sir William Douglas, Lord of Liddesdale, also known as the Knight of Liddesdale and the Flower of Chivalry, was a Scottish nobleman and soldier active during the Second War of Scottish Independence.

The Battle of Annan, also known in the sources as the Camisade of Annan, took place on 16 December 1332 at Annan, Dumfries and Galloway in Scotland.

The sack of Berwick was the first significant battle of the First War of Scottish Independence in 1296.

Edward Balliol or Edward de Balliol was a claimant to the Scottish throne during the Second War of Scottish Independence. With English help, he ruled parts of the kingdom from 1332 to 1356.

The Second War of Scottish Independence broke out in 1332, when Edward Balliol led an English-backed invasion of Scotland. Balliol, the son of former Scottish king John Balliol, was attempting to make good his claim to the Scottish throne. He was opposed by Scots loyal to the occupant of the throne, eight-year-old David II. At the Battle of Dupplin Moor Balliol's force defeated a Scottish army ten times their size and Balliol was crowned king. Within three months David's partisans had regrouped and forced Balliol out of Scotland. He appealed to the English king, Edward III, who invaded Scotland in 1333 and besieged the important trading town of Berwick. A large Scottish army attempted to relieve it but was heavily defeated at the Battle of Halidon Hill. Balliol established his authority over most of Scotland, ceded to England the eight counties of south-east Scotland and did homage to Edward for the rest of the country as a fief.

Sir Andrew Murray (1298–1338), also known as Sir Andrew Moray, or Sir Andrew de Moray, was a Scottish military and political leader who supported King David II of Scotland against Edward Balliol and King Edward III of England during the Second War of Scottish Independence. He held the lordships of Avoch and Petty in north Scotland, and Bothwell in west-central Scotland. In 1326 he married Christina Bruce, a sister of King Robert I of Scotland. Murray was twice chosen as Guardian of Scotland, first in 1332, and again from 1335 on his return to Scotland after his release from captivity in England. He held the guardianship until his death in 1338.

The Battle of Kinghorn was fought on 6 August 1332 at Wester Kinghorn, Fife, Scotland. An invading seaborne force of 1,500 men was commanded by Edward Balliol and Henry Beaumont, Earl of Buchan. A Scottish army, possibly 4,000 strong, commanded by Duncan, Earl of Fife, and Robert Bruce, Lord of Liddesdale was defeated with heavy loss. Balliol was the son of King John Balliol and was attempting to make good his claim to be the rightful king of Scotland. He hoped that many of the Scots would desert to him.

Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton Castle in the parish of Cornhill-on-Tweed, Northumberland, was a soldier who served throughout the wars of Scottish Independence. His experiences were recorded by his son Thomas Grey in his chronicles, and provide a rare picture of the day-to-day realities of the wars.

The siege of Berwick lasted four months in 1333 and resulted in the Scottish-held town of Berwick-upon-Tweed being captured by an English army commanded by King Edward III. The year before, Edward Balliol had seized the Scottish Crown, surreptitiously supported by Edward III. He was shortly thereafter expelled from the kingdom by a popular uprising. Edward III used this as a casus belli and invaded Scotland. The immediate target was the strategically important border town of Berwick.

The English invasion of Scotland of 1296 was a military campaign undertaken by Edward I of England in retaliation to the Scottish treaty with France and the renouncing of fealty of John, King of Scotland and Scottish raids into Northern England.

Burnt Candlemas was a failed invasion of Scotland in early 1356 by an English army commanded by King Edward III, and was the last campaign of the Second War of Scottish Independence. Tensions on the Anglo-Scottish border led to a military build-up by both sides in 1355. In September a nine-month truce was agreed, and most of the English forces left for northern France to take part in a campaign of the concurrent Hundred Years' War. A few days after agreeing the truce, the Scots, encouraged and subsidised by the French, broke it, invading and devastating Northumberland. In late December the Scots escaladed and captured the important English-held border town of Berwick-on-Tweed and laid siege to its castle. The English army redeployed from France to Newcastle in northern England.