The English Civil War was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Royalists and Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, the struggle consisted of the First English Civil War and the Second English Civil War. The Anglo-Scottish War of 1650 to 1652 is sometimes referred to as the Third English Civil War.

The Battle of Marston Moor was fought on 2 July 1644, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of 1639–1653. The combined forces of the English Parliamentarians under Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester and the Scottish Covenanters under the Earl of Leven defeated the Royalists commanded by Prince Rupert of the Rhine and the Marquess of Newcastle.

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1642 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell defeated a largely Scottish Royalist force of 16,000 led by Charles II of England.

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, KB, PC was an English Parliamentarian and soldier during the first half of the 17th century. With the start of the Civil War in 1642, he became the first Captain-General and Chief Commander of the Parliamentarian army, also known as the Roundheads. However, he was unable and unwilling to score a decisive blow against the Royalist army of King Charles I. He was eventually overshadowed by the ascendancy of Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax, and resigned his commission in 1646.

The Battle of Naseby took place on 14 June 1645 during the First English Civil War, near the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Parliamentarian New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, destroyed the main Royalist army under Charles I and Prince Rupert. The defeat ended any real hope of royalist victory, although Charles did not finally surrender until May 1646.

The Battle of Edgehill was a pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642.

Sir William Waller JP was an English soldier and politician, who commanded Parliamentarian armies during the First English Civil War. Elected MP for Andover to the Long Parliament in 1640, Waller relinquished his military positions under the Self-denying Ordinance in 1645. Although deeply religious and a devout Puritan, he belonged to the moderate Presbyterian faction, who opposed the involvement of the New Model Army in politics post 1646. As a result, he was one of the Eleven Members excluded by the army in July 1647, then again by Pride's Purge in December 1648 for refusing to support the Trial of Charles I, and his subsequent execution in January 1649.

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. An estimated 15% to 20% of adult males in England and Wales served in the military at some point between 1639 and 1653, while around 4% of the total population died from war-related causes. These figures illustrate the widespread impact of the conflict on society, and the bitterness it engendered as a result.

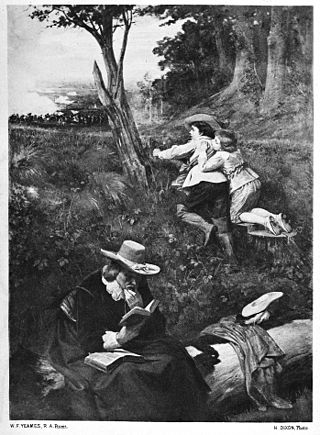

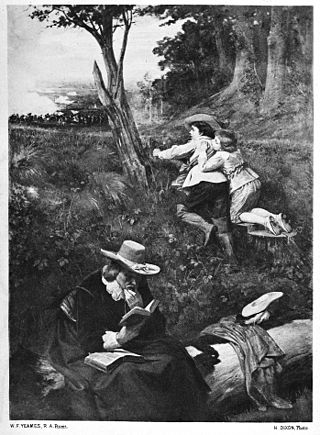

The First Battle of Newbury was a battle of the First English Civil War that was fought on 20 September 1643 between a Royalist army, under the personal command of King Charles, and a Parliamentarian force led by the Earl of Essex. Following a year of Royalist battlefield successes, in which they took Banbury, Oxford and Reading without conflict before storming Bristol, the Parliamentarians were left without an effective army in the west of England. When Charles laid siege to Gloucester, Parliament was forced to muster a force under Essex with which to beat Charles' forces off. After a long march, Essex surprised the Royalists and forced them away from Gloucester before beginning a retreat to London. Charles rallied his forces and pursued Essex, overtaking the Parliamentarian army at Newbury and forcing them to march past the Royalist force to continue their retreat.

Sir John Urry, also known as Hurry, was a Scottish professional soldier who at various times during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms fought for Scots Covenanters, Engagers and Royalists, as well as both English Parliamentarians and Royalists. Captured at Carbisdale in April 1650, he was executed in Edinburgh on 29 May 1650.

The Battle of Turnham Green took place on 13 November 1642 near the village of Turnham Green, at the end of the first campaigning season of the First English Civil War. The battle resulted in a standoff between the forces of King Charles I and the much larger Parliamentarian army under the command of the Earl of Essex. In blocking the Royalist army's way to London immediately, however, the Parliamentarians gained an important strategic victory as the standoff forced Charles and his army to retreat to Oxford for secure winter quarters.

The Battle of Chalgrove Field took place on 18 June 1643, during the First English Civil War, near Chalgrove, Oxfordshire. It is now best remembered for the death of John Hampden, who was wounded in the shoulder during the battle and died six days later.

The Battle of Brentford was a small pitched battle which took place on 12 November 1642 in Brentford, Middlesex, between a detachment of the Royalist army under the command of Prince Rupert, and two infantry regiments of Parliamentarians with some horse in support. The result was a victory for the Royalists.

The Storming of Bolton, sometimes referred to as the "Bolton massacre", was an event in the First English Civil War which happened on 28 May 1644. The strongly Parliamentarian town was stormed and captured by Royalist forces under Prince Rupert. It was alleged that up to 1,600 of Bolton's defenders and inhabitants were slaughtered during and after the fighting. The "massacre at Bolton" became a staple of Parliamentarian propaganda.

The First English Civil War started in 1642. By the end of the year neither side had succeeded in gaining an advantage, although the King's advance on London was the closest Royalist forces came to threatening the city.

Worcestershire was the county where the first battle and last battle of the English Civil War took place. The first battle, the Battle of Powick Bridge, fought on 23 September 1642, was a cavalry skirmish and a victory for the Royalists (Cavaliers). The final battle, the battle of Worcester, fought on 3 September 1651, was decisive and ended the war with a Parliamentary (Roundhead) victory and King Charles II a wanted fugitive.

The Battle of Kings Norton was fought on 17 October 1642. The skirmish developed out of a chance encounter between Royalists under the command of Prince Rupert and Parliamentarians under the command of Lord Willoughby. Both forces had been on their way to join their respective armies which were later to meet at Edgehill in the first pitched battle of the First English Civil War. The Parliamentarians won the encounter and both forces proceeded to join their respective armies.

The Storming of Farnham Castle occurred on 1 December 1642, during the early stages of the First English Civil War, when a Parliamentarian force attacked the Royalist garrison at Farnham Castle in Surrey. Sir John Denham had taken possession of the castle for the Royalists in mid-November, but after the Royalists had been turned back from London at the Battle of Turnham Green, a Parliamentarian force under the command of Sir William Waller approached the castle. After Denham refused to surrender, Waller's forces successfully stormed the castle. They captured it in under three hours, mostly due to the unwillingness of the Royalist troops to fight. This allowed the Parliamentarians to get close enough to breach the gates, after which the garrison surrendered.

The battle of Piercebridge was fought on 1 December 1642 in County Durham, England, during the First English Civil War. The Earl of Newcastle was advancing with an army of 6,000 from Newcastle upon Tyne to York to reinforce the local Royalists. Aware of his approach, the Parliamentarians defended the main crossing over the River Tees, at Piercebridge. Under the command of Captain John Hotham, around 580 troops had barricaded the bridge.

The Battle of Winwick was fought on 19 August 1648 near the Lancashire village of Winwick between part of a Royalist army under Lieutenant General William Baillie and a Parliamentarian army commanded by Lieutenant General Oliver Cromwell. The Royalists were defeated with all of those who took part in the fighting, their army's entire infantry force, either killed or captured. The Royalist mounted component fled but surrendered five days after the battle. Winwick was the last battle of the Second English Civil War.