| Portrait | Bearer | Standard | Notes |

|---|

| Edward III |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Per fess, azure and gules. A Lion of England imperially crowned. In chief a coronet of crosses pattée and fleurs-de-lys, between two clouds irradiated proper; and in base a cloud between two coronets. DIEU ET MON. In chief a coronet, and in base an irradiated cloud. DROYT. Quarterly 1 & 4, an irradiated cloud, 2 & 3, a coronet. |

|---|

| Richard II |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Hart lodged argent, attired, unguled, ducally gorged and chained or, between four suns in splendour. DIEU ET MON. Two suns in splendour. DROYT. Four suns in splendour. |

|---|

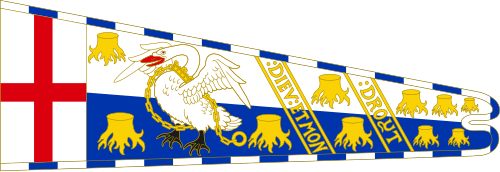

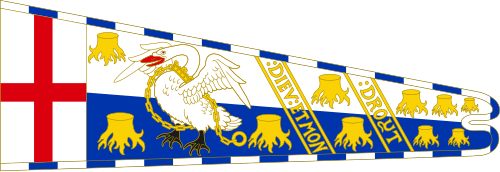

| Henry V |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and azure. A Swan with wings displayed argent, beaked gules, membered sable, ducally gorged and chained or, between three stumps of trees, one in dexter chief, and two in base of the last. DIEU ET MON. Two tree-stumps in pale or. DROYT. Five tree-stumps, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

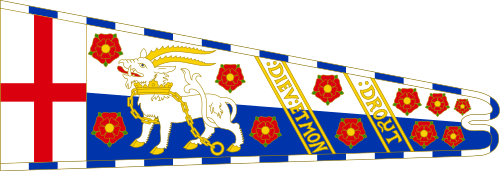

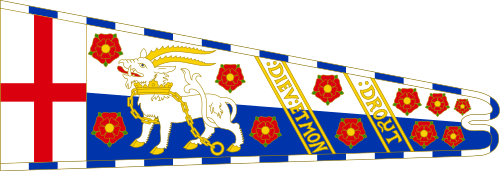

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and azure. Heraldic Antelope at gaze argent, maned, tufted, ducally gorged & chained or, chain reflexed over the back, between four roses gules. DIEU ET MON. Two roses in pale gules. DROYT. Five roses, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

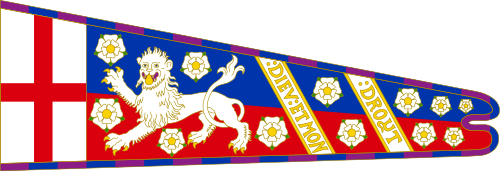

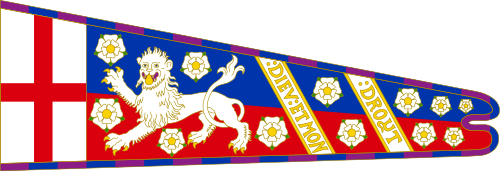

| Edward IV |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White Lion of March, between roses, barbed, seeded argent. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White rose of York, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or, in base a rose argent, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A Lion of England imperially crowned, between three roses gules in chief, and as many argent in base, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose gules, and in base another argent. DROYT. In chief two roses gules, and in base as many argent. |

|---|

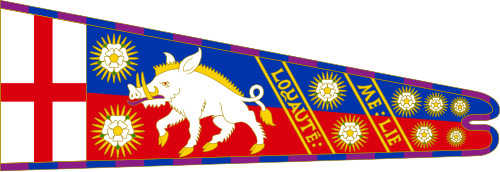

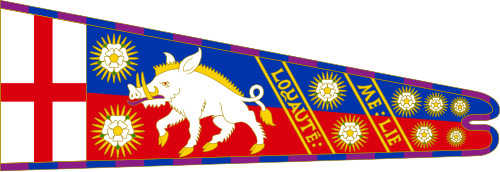

| Richard III |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White boar of Richard III, between roses argent, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or, LOYAUTE. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. ME LIE. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

| Henry VII |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A Dragon gules, between two flames proper, and two in base. DIEU ET MON. A flame proper in chief and in base. DROYT. In chief three flames proper, in base two. |

|---|

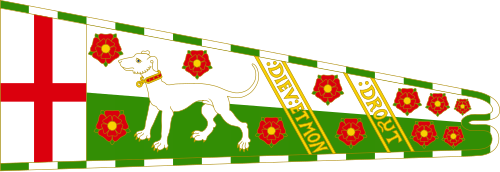

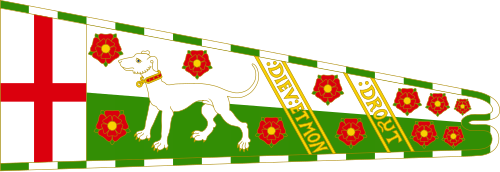

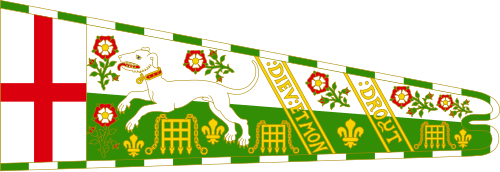

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Greyhound of Richmond, statant argent, collared gules. between roses, barbed, seeded gules. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose gules, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses gules, three in chief, and two in base. |

|---|

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules. A Lion of England imperially crowned. Whole being seme of Tudor roses irradiated or, and Fleurs-de-lys also or. |

|---|

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert, bordered murrey and azure. A Dragon gules, between two roses of the last in chief, and three in base, argent. DIEU ET MON. A rose gules in chief, rose argent in base. DROYT. In chief three roses gules, in base two argent. |

|---|

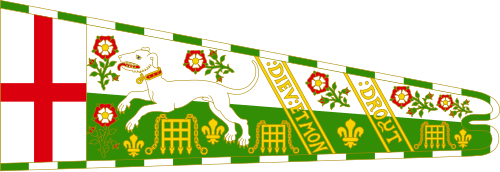

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Greyhound of Richmond, courant argent, collared gules. Whole being seme of Tudor roses, Portcullises, and Fleurs-de-lys or. |

|---|

| Henry VIII |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A Dragon gules, Whole being seme of Tudor roses proper, flames gules, and Fleurs-de-lys or. |

|---|

| Charles I |  | A large red streamer, pennon shaped, cloven at the end, attached to a long red staff having about twenty supporters, and bore next the staff a St George's Cross, then an escutcheon of the Royal Arms, with a hand pointing to the crown above it, and the legend: "GIVE UNTO CAESAR HIS DUE," together with two other crowns, each surmounted by a lion passant. Raised over Nottingham on 22 August 1642. [11] |

|---|

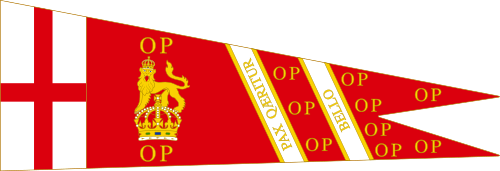

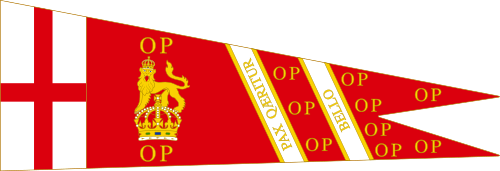

| Oliver Cromwell |  | At the head of the standard, a square argent, and thereon a red Cross of St George, Patron of England; and in the tail or flying part thereof, gules, a lion of England gardant, and crowned royally, standing on a crown Imperial, all of gold, properly ornamented; next on two bends of silver, in Roman letters of gold, the motto of the Commonwealth, viz. PAX QÆRITUR BELLO, and in vacant places OP “in ye ſtyle Gange-Namme”. Only raised at his funeral on 23 November 1658. [12] |

|---|