Related Research Articles

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings, as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branch of heraldry, concerns the design and transmission of the heraldic achievement. The achievement, or armorial bearings usually includes a coat of arms on a shield, helmet and crest, together with any accompanying devices, such as supporters, badges, heraldic banners and mottoes.

The coat of arms of England is the coat of arms historically used as arms of dominion by the monarchs of the Kingdom of England, and now used to symbolise England generally. The arms were adopted c.1200 by the Plantagenet kings and continued to be used by successive English and British monarchs; they are currently quartered with the arms of Scotland and Ireland in the coat of arms of the United Kingdom. Historically they were also quartered with the arms of France, representing the English claim to the French throne, and Hanover.

In heraldry, cadency is any systematic way to distinguish arms displayed by descendants of the holder of a coat of arms when those family members have not been granted arms in their own right. Cadency is necessary in heraldic systems in which a given design may be owned by only one person at any time, generally the head of the senior line of a particular family.

In heraldry, a bend is a band or strap running from the upper dexter corner of the shield to the lower sinister. Authorities differ as to how much of the field it should cover, ranging from one-fifth up to one-third.

In heraldry, a label is a charge resembling the strap crossing the horse's chest from which pendants are hung. It is usually a mark of difference, but has sometimes been borne simply as a charge in its own right.

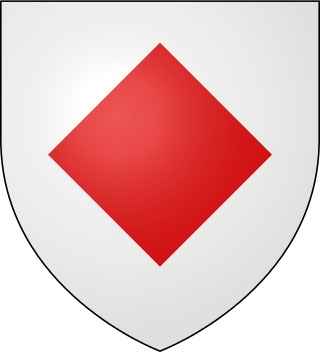

The lozenge in heraldry is a diamond-shaped rhombus charge, usually somewhat narrower than it is tall. It is to be distinguished in modern heraldry from the fusil, which is like the lozenge but narrower, though the distinction has not always been as fine and is not always observed even today. A mascle is a voided lozenge—that is, a lozenge with a lozenge-shaped hole in the middle—and the rarer rustre is a lozenge containing a circular hole in the centre. A lozenge throughout has "four corners touching the border of the escutcheon". A field covered in a pattern of lozenges is described as lozengy; similar fields of mascles are masculy, and fusils, fusily. In civic heraldry, a lozenge sable is often used in coal-mining communities to represent a lump of coal.

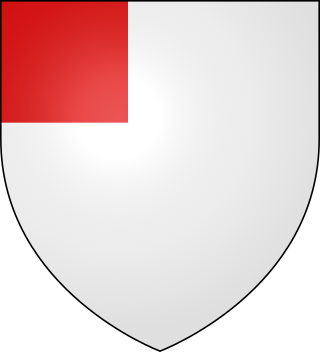

In heraldic blazon, a chief is a charge on a coat of arms that takes the form of a band running horizontally across the top edge of the shield. Writers disagree in how much of the shield's surface is to be covered by the chief, ranging from one-fourth to one-third. The former is more likely if the chief is uncharged, that is, if it does not have other objects placed on it. If charged, the chief is typically wider to allow room for the objects drawn there.

In heraldry, a canton is a charge placed upon a shield. It is, by default a square in the upper dexter corner, but if in the sinister corner is blazoned a canton sinister. A canton is classed by some heraldic writers as one of the honorable ordinaries; but, strictly speaking, it is a diminutive of the quarter, being two-thirds the area of that ordinary. However, in the armorial roll of Henry III, the quarter appears in several coats which in later rolls are blazoned as cantons. The canton, like the quarter, appears in early arms, and is always shown with straight lines.

The Heraldry Society is a British organization that is devoted to studying and promoting heraldry and related subjects. In 1947, a twenty-year-old John Brooke-Little founded the Society of Heraldic Antiquaries. This name was changed to The Heraldry Society in 1950. It was incorporated in 1956 and is now a registered educational charity, with the registered charity number 241456.

Heraldry in Scotland, while broadly similar to that practised in England and elsewhere in western Europe, has its own distinctive features. Its heraldic executive is separate from that of the rest of the United Kingdom.

John Philip Brooke Brooke-Little was an English writer on heraldic subjects, and a long-serving herald at the College of Arms in London. In 1947, while still a student, Brooke-Little founded the Society of Heraldic Antiquaries, now known as the Heraldry Society and recognised as one of the leading learned societies in its field. He served as the society's chairman for 50 years and then as its president from 1997 until his death in 2006.

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb to blazon means to create such a description. The visual depiction of a coat of arms or flag has traditionally had considerable latitude in design, but a verbal blazon specifies the essentially distinctive elements. A coat of arms or flag is therefore primarily defined not by a picture but rather by the wording of its blazon. Blazon is also the specialized language in which a blazon is written, and, as a verb, the act of writing such a description. Blazonry is the art, craft or practice of creating a blazon. The language employed in blazonry has its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax, which becomes essential for comprehension when blazoning a complex coat of arms.

The House of Plantagenet was the first truly armigerous royal dynasty of England. Their predecessor, Henry I of England, had presented items decorated with a lion heraldic emblem to his son-in-law, Plantagenet founder Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, and his family experimented with different lion-bearing coats until these coalesced during the reign of his grandson, Richard I (1189–1199), into a coat of arms with three lions on a red field, formally Gules, three lions passant guardant or , that became the Royal Arms of England, and colloquially those of England itself. The various cadet branches descended from this family bore differenced versions of these arms, while later members of the House of Plantagenet would either quarter or impale these arms with others to reflect their political aspirations.

Delhi Herald of Arms Extraordinary was a British officer of arms whose office was created in 1911 for the Delhi Durbar. Though an officer of the crown, Delhi Herald Extraordinary was not a member of the corporation of the College of Arms in London and his duties were more ceremonial than heraldic.

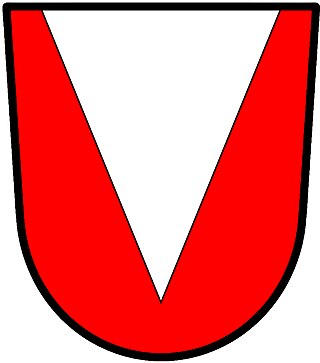

In heraldry, a pile is a charge usually counted as one of the ordinaries. It consists of a wedge emerging from the upper edge of the shield and converging to a point near the base. If it touches the base, it is blazoned throughout.

English heraldry is the form of coats of arms and other heraldic bearings and insignia used in England. It lies within the so-called Gallo-British tradition. Coats of arms in England are regulated and granted to individuals by the English kings of arms of the College of Arms. An individual's arms may also be borne 'by courtesy' by members of the holder's nuclear family, subject to a system of cadency marks, to differentiate those displays from the arms of the original holder. The English heraldic style is exemplified in the arms of British royalty, and is reflected in the civic arms of cities and towns, as well as the noble arms of individuals in England. Royal orders in England, such as the Order of the Garter, also maintain notable heraldic bearings.

In English heraldry an heraldic heiress is a daughter of a deceased man who was entitled to a coat of arms and who carries forward the right to those arms for the benefit of her future male descendants. This carrying forward only applies if she has no brothers or other male relatives alive who would inherit the arms on the death of the holder.

In heraldry, a bar is an ordinary consisting of a horizontal band across the shield. If only one bar appears across the middle of the shield, it is termed a fess; if two or more appear, they can only be called bars. Calling the bar a diminutive of the fess is inaccurate, however, because two bars may each be no smaller than a fess. Like the fess, bars too may bear complex lines. The diminutive form of the bar is the barrulet, though these frequently appear in pairs, the pair termed a "bar gemel" rather than "two barrulets".

The royal supporters of England are the heraldic supporter creatures appearing on each side of the royal arms of England. The royal supporters of the monarchs of England displayed a variety, or even a menagerie, of real and imaginary heraldic beasts, either side of their royal arms of sovereignty, including lion, leopard, panther and tiger, antelope and hart, greyhound, boar and bull, falcon, cock, eagle and swan, red and gold dragons, as well as the current unicorn.

Heraldic labels are used to differentiate the personal coats of arms of members of the royal family of the United Kingdom from that of the monarch and from each other. In the Gallo-British heraldic tradition, cadency marks have been available to "difference" the arms of a son from those of his father, and the arms of brothers from each other, and traditionally this was often done when it was considered important for each man to have a distinctive individual coat of arms and/or to differentiate the arms of the head of a house from junior members of the family. This was especially important in the case of arms of sovereignty: to use the undifferenced arms of a kingdom is to assert a claim to the throne. Therefore, in the English royal family, cadency marks were used from the time of Henry III, typically a label or bordure alluding to the arms of the bearer's mother or wife. After about 1340, when Edward III made a claim to the throne of France, a blue label did not contrast sufficiently with the blue field of the French quarter of the royal arms; accordingly most royal cadets used labels argent: that of the heir apparent was plain, and all others were charged. Bordures of various tinctures continued to be used into the 15th century.

References

- John Brooke-Little (Norroy and Ulster King of Arms): An Heraldic Alphabet (new and revised edition). Robson Books, London, 1985.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies: A Complete Guide to Heraldry (revised and annotated by J.P. Brooke-Little, Richmond Herald). Nelson, London, 1969.