Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

The Bodleian Library is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in Britain after the British Library. Under the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003, it is one of six legal deposit libraries for works published in the United Kingdom, and under Irish law it is entitled to request a copy of each book published in the Republic of Ireland. Known to Oxford scholars as "Bodley" or "the Bod", it operates principally as a reference library and, in general, documents may not be removed from the reading rooms.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Ælfric of Eynsham was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. He is also known variously as Ælfric the Grammarian, Ælfric of Cerne, and Ælfric the Homilist. In the view of Peter Hunter Blair, he was "a man comparable both in the quantity of his writings and in the quality of his mind even with Bede himself." According to Claudio Leonardi, he "represented the highest pinnacle of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature".

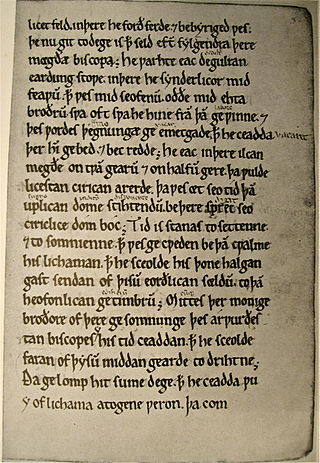

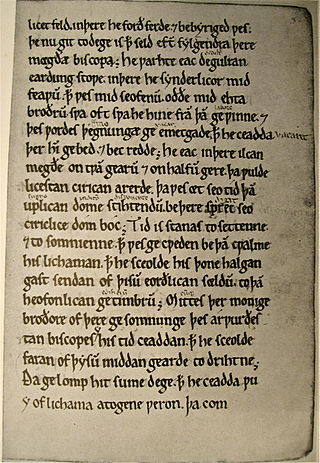

"Hebban olla vogala", sometimes spelled "hebban olla uogala", are the first three words of an 11th-century text fragment written in Old Dutch. The fragment was discovered in 1932 on the back of the end-leaf of a manuscript that once belonged to the cathedral priory of Rochester, Kent, now Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 340. The manuscript contains a collection of Old English sermons by Ælfric of Eynsham. The Dutch text is found on fol. 169v and probably dates to the late 11th century. It was long considered to represent a West Flemish variant of Old Low Franconian, although more recent research shows that it also displays significant influence from Old English.

The Textus Roffensis, fully titled the Textus de Ecclesia Roffensi per Ernulphum episcopum and sometimes also known as the Annals of Rochester, is a mediaeval manuscript that consists of two separate works written between 1122 and 1124. It is catalogued as "Rochester Cathedral Library, MS A.3.5" and as of 2023 is currently on display in a new exhibition at Rochester Cathedral in Rochester, Kent. It is thought that the main text of both manuscripts was written by a single scribe, although the English glosses to the two Latin entries were made by a second hand. The annotations might indicate that the manuscript was consulted in some post-Conquest trials. However, the glosses are very sparse and just clarify a few uncertain terms. For example, the entry on f. 67r merely explains that the triplex iudiciu(m) is called in English, ofraceth ordel.

West Saxon is the term applied to the two different dialects Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon with West Saxon being one of the four distinct regional dialects of Old English. The three others were Kentish, Mercian and Northumbrian. West Saxon was the language of the kingdom of Wessex, and was the basis for successive widely used literary forms of Old English: the Early West Saxon of Alfred the Great's time, and the Late West Saxon of the late 10th and 11th centuries. Due to the Saxons' establishment as a politically dominant force in the Old English period, the West Saxon dialects became the strongest dialects in Old English manuscript writing.

Probatio pennae is the medieval term for breaking in a new pen, and used to refer to text written to test a newly cut pen.

The Vercelli Book is one of the oldest of the four Old English Poetic Codices. It is an anthology of Old English prose and verse that dates back to the late 10th century. The manuscript is housed in the Capitulary Library of Vercelli, in northern Italy.

The Winchester Troper refers to two eleventh-century manuscripts of liturgical plainchant and two-voice polyphony copied and used in the Old Minster at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire, England. The manuscripts are now held at Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 473 and Oxford, Bodleian Library Bodley 775 . The term "Winchester Troper" is best understood as the repertory of music contained in the two manuscripts. Both manuscripts contain a variety of liturgical genres, including Proper and Ordinary chants for both the Mass and the Divine Office. Many of the chants can also be found in other English and Northern French tropers, graduals, and antiphoners. However, some chants are unique to Winchester, including those for local saints such as St. Æthelwold and St. Swithun, who were influential Bishops of Winchester in the previous centuries. Corpus 473 contains the most significant and largest surviving collection of eleventh-century organum. This polyphonic repertoire is unique to that manuscript.

The Wonders of the East is an Old English prose text, probably written around AD 1000. It is accompanied by many illustrations and appears also in two other manuscripts, in both Latin and Old English. It describes a variety of odd, magical and barbaric creatures that inhabit Eastern regions, such as Babylonia, Persia, Egypt, and India. The Wonders can be found in three extant manuscripts from the 11th and 12th centuries, the earliest of these being the famous Nowell Codex, which is also the only manuscript containing Beowulf. The Old English text was originally translated from a Latin text now referred to as De rebus in Oriente mirabilibus, and remains mostly faithful to the Latin original.

The Anglian collection is a collection of Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies and regnal lists. These survive in four manuscripts; two of which now reside in the British Library. The remaining two belong to the libraries of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and Rochester Cathedral, the latter now deposited with the Medway Archives.

The Tremulous Hand of Worcester is the name given to a 13th-century scribe of Old English manuscripts with handwriting characterized by large, shaky, leftward leaning figures usually written in light brown ink. He is assumed to have worked in Worcester Priory, because all manuscripts identified as his work have been connected to Worcester.

Baroccianus is an adjective applied to manuscripts indicating an origin in the Baroccianum, a Venetian collection assembled by the humanist Francesco Barozzi (Barocius). A large part of that collection was sold after the death of Iacopo Barozzi or Barocci (1562–1617), nephew and heir to Francesco; and the purchase by William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke led in turn to his donation in 1629 of a substantial collection of Greek manuscripts from the Baroccianum to the Bodleian Library. The designation Codex Baroccianus followed by a number is an indication that a manuscript is in the Bodleian Catalogue and has its provenance in this donation.

The Old English Hexateuch, or Aelfric Paraphrase, is the collaborative project of the late Anglo-Saxon period that translated the six books of the Hexateuch into Old English, presumably under the editorship of Abbot Ælfric of Eynsham. It is the first English vernacular translation of the first six books of the Old Testament, i.e. the five books of the Torah and Joshua. It was probably made for use by lay people.

The Lambeth Homilies are a collection of homilies found in a manuscript in Lambeth Palace Library, London. The collection contains seventeen sermons and is notable for being one of the latest examples of Old English, written as it was c. 1200, well into the period of Middle English.

Hatton Gospels is the name now given to a manuscript produced in the late 12th century or early 13th century. It contains a translation of the four gospels into the West Saxon dialect of Old English. It is a nearly complete gospel book, missing only a small part of the Gospel of Luke. It is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, as MS Hatton 38. The fullest description of the manuscript is by Takako Kato, in Treharne, et al., eds., Production and Use of English Manuscripts, 1020-1220.

Robert of Cricklade was a medieval English writer and prior of St Frideswide's Priory in Oxford. He was a native of Cricklade and taught before becoming a cleric. He wrote several theological works as well as a lost biography of Thomas Becket, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury.

De raris fabulis is a collection of 23 or 24 short Latin dialogues from 9th- or 10th-century Celtic Britain. The dialogues belong to the genre known as the colloquy. These were pedagogical texts for teaching Latin in monastic schools.