This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A homiliarium or homiliary is a collection of homilies, or familiar explanations of the Gospels.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A homiliarium or homiliary is a collection of homilies, or familiar explanations of the Gospels.

From a very early time the homilies of the Fathers were in high esteem, and were read in connection with the recitation of the Divine Office (see also Breviary). St. Gregory the Great refers to this custom, and St. Benedict mentions it in his rule, dating it to as early as the sixth century. [1] This was particularly true of the homilies of Pope Leo I, very terse and peculiarly suited to liturgical purposes.

As new feasts were added to the Office, the demand for homilies became greater and by the eighth century, the century of liturgical codification, collections of homilies began to appear. [2] Such a collection was called a homiliarium, or homiliarius (i.e. liber) doctorum. In the early Middle Ages numerous collections of homilies were made for purposes of preaching.

Many homiliaria have survived, and there are medieval references to many others. Mabillon (De Liturgia Gallicana) mentions a very old Gallican homiliarium. A manuscript of the eighth century refers to a homiliarium by Agimundus, a Roman priest. The Venerable Bede compiled one in England. In the episcopal library at Würzburg there is preserved a homiliarium by Bishop Burchard, a companion of St. Boniface. Alanus, Abbot of Farfa (770), compiled a large homiliarium, which must have been often copied, for it has reached us in several manuscripts. In the first half of the ninth century Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel compiled from the Fathers a book of homilies on the Gospels and Epistles for the whole year. Haymo, a monk of Fulda and disciple of Alcuin, afterwards Bishop of Halberstadt (841), made a collection for Sundays and feasts of the saints. [3] Rabanus Maurus, another pupil of Alcuin, and Eric of Auxerre compiled each a collection of homilies. All these wrote in Latin.

Perhaps the most famous homiliarium is that of Paul Warnefrid, better known as Paul the Deacon, a monk of Monte Cassino. It was made by order of Charlemagne.

The purpose of this work is disputed. Johann Lorenz von Mosheim [4] and August Neander, [5] followed by various encyclopedias and many Protestant writers, describe it as compiled in order that the clergy might at least recite to the people the Gospels and Epistles on Sundays and holidays. The Catholic Encyclopedia disagrees, saying that the royal decree clarifies that this particular collection was not made for pulpit use but for the recitation of the Breviary, and that copies were made only for such churches as were wont to recite the Office in choir.

Manuscript copies of this homiliarium are found at Heidelberg, Frankfurt, Darmstadt, Fulda, Gießen and Kassel. The manuscript mentioned by Mabillon, and rediscovered by Ranke, in Karlsruhe, is older than the tenth century Monte Cassino copy. The earliest printed edition is that of Speyer in 1482. In the Cologne edition (sixteenth century) the authorship is ascribed to Alcuin, but the royal decree alluded to leaves no doubt as to the purpose or author; Alcuin may have revised it. As the fifteenth or sixteenth century, this work was in use for homiletic purposes.

During the English Reformation, Thomas Cranmer and others saw the need for local congregations to be taught Anglican theology and practice. Since many priests and deacons were still uneducated, semi-literate and tending toward Roman Catholicism in their teachings and activities, it was decided to create a series of homilies to be read out during the church service by the local Priest.

The First book of Homilies contained twelve sermons and was written mainly by Cranmer. They focused strongly upon the character of God and Justification by Faith and were fully published by 1547.

The Second book of Homilies contained twenty-one sermons and was written mainly by Bishop John Jewel, and were fully published by 1571. These were more practical in their application and focused more on living the Christian life.

The reading of the Homilies as part of the church service was supported by Article XXXV of the Thirty-Nine Articles.

Translations of homilies were frequently ordered by the Catholic Church, [6] and became common. Alfred the Great translated into Anglo-Saxon the homilies of Venerable Bede, and for the clergy the "Regula Pastoralis" of St. Gregory the Great. Ælfric selected and translated into the same language passages from St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Jerome, Bede, St. Gregory, Smaragdus and occasionally from Haymo. His aim was to work the extracts into a whole, and thus present them in an easy and intelligible style. [7] The first German translation of this kind was due to Ottfried of Weißenburg.

Collections of the homilies of the Greek and Latin Church Fathers will be found in Migne's "Patrology". An account of the editions of their works, homilies included, is in Otto Bardenhewer's Patrology. [8] The surviving Irish homilies are found principally in "The Speckled Book" (Leabhar Breac), which is written partly in Latin and partly in Irish. [9] It is largely taken up with homilies and passions, lives of the saints etc. The "Book of Ballymote" contains, amongst miscellaneous subjects, Biblical and hagiological matter; and the "Book of Lismore" contains lives of the saints under the form of homilies. [10]

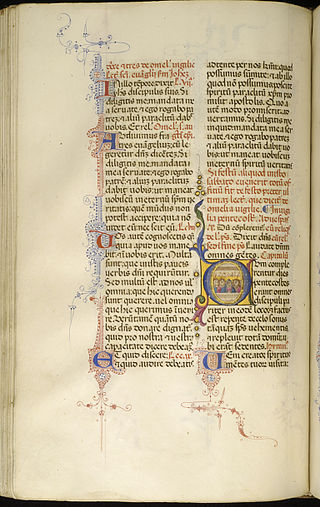

The binding and illumination of gospels and homiliaria were both elaborate and artistic. They were frequently deposited in a highly wrought casket (Arca Testamenti), which in Ireland was called cumdach (shrine). Emperor Constantine the Great presented a text of the Gospels with costly binding to the church of St. John Lateran; and Queen Theodolinda made a similar presentation to the church at Monza. [11]

Bede, also known as Saint Bede, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable, was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the greatest teachers and writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most famous work, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, gained him the title "The Father of English History". He served at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom of Northumbria of the Angles.

The Roman Breviary is a breviary of the Roman Rite in the Catholic Church. A liturgical book, it contains public or canonical prayers, hymns, the Psalms, readings, and notations for everyday use, especially by bishops, priests, and deacons in the Divine Office.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Boniface was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of Francia during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made bishop of Mainz by Pope Gregory III. He was martyred in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they rest in a sarcophagus which remains a site of Christian pilgrimage.

John Lingard was an English Catholic priest and historian, the author of The History of England, From the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII, an eight-volume work published in 1819. Lingard was a teacher at the English College at Douai, and at the seminary at Crook Hall, and later St. Cuthbert's College. In 1811 he retired to Hornby in Lancashire to continue work on his writing.

Willibrord was an Anglo-Saxon monk, bishop, and missionary. He became the first Bishop of Utrecht in what is now the Netherlands, dying at Echternach in Luxembourg, and is known as the "Apostle to the Frisians".

The St Cuthbert Gospel, also known as the Stonyhurst Gospel or the St Cuthbert Gospel of St John, is an early 8th-century pocket gospel book, written in Latin. Its finely decorated leather binding is the earliest known Western bookbinding to survive, and both the 94 vellum folios and the binding are in outstanding condition for a book of this age. With a page size of only 138 by 92 millimetres, the St Cuthbert Gospel is one of the smallest surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. The essentially undecorated text is the Gospel of John in Latin, written in a script that has been regarded as a model of elegant simplicity.

Ælfric of Eynsham was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. He is also known variously as Ælfric the Grammarian, Ælfric of Cerne, and Ælfric the Homilist. In the view of Peter Hunter Blair, he was "a man comparable both in the quantity of his writings and in the quality of his mind even with Bede himself." According to Claudio Leonardi, he "represented the highest pinnacle of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature".

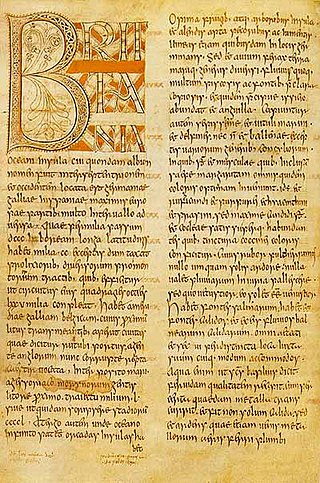

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between the pre-Schism Roman Rite and Celtic Christianity. It was composed in Latin, and is believed to have been completed in 731 when Bede was approximately 59 years old. It is considered one of the most important original references on Anglo-Saxon history, and has played a key role in the development of an English national identity.

Wigbert, (Wihtberht) born in Wessex around 675, was an Anglo-Saxon Benedictine monk and a missionary and disciple of Boniface who travelled with the latter in Frisia and northern and central Germany to convert the local tribes to Christianity. His feast day is August 13 in the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.

British Library, Add MS 11848 is an illuminated Carolingian Latin Gospel Book produced at Tours. It contains the Vulgate translation of the four Gospels written on vellum in Carolingian minuscule with Square and Rustic Capitals and Uncials as display scripts. The manuscript has 219 extant folios which measure approximately 330 by 230 mm. The text is written in area of about 205 by 127 mm. In addition to the text of the Gospels, the manuscript contains the letter of St. Jerome to Pope Damasus and of Eusebius of Caesarea to Carpian, along with the Eusebian canon tables. There are prologues and capitula lists before each Gospel. A table of readings for the year was added, probably between 1675 and 1749, to the end of the volume. This is followed by a list of capitula incipits and a word grid which were added in the Carolingian period.

Peter Chrysologus was an Italian Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Ravenna from about 433 until his death. He is known as the "Doctor of Homilies" for the concise but theologically rich reflections he delivered during his time as the Bishop of Ravenna.

The term "Celtic Rite" is applied to the various liturgical rites used in Celtic Christianity in Britain, Ireland and Brittany and the monasteries founded by St. Columbanus and Saint Catald in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy during the Early Middle Ages. The term is not meant to imply homogeneity; instead it is used to describe a diverse range of liturgical practices united by lineage and geography.

The Blickling homilies are a collection of anonymous homilies from Anglo-Saxon England. They are written in Old English, and were written down at some point before the end of the tenth century, making them one of the oldest collections of sermons to survive from medieval England, the other main witness being the Vercelli Book. Their name derives from Blickling Hall in Norfolk, which once housed them; the manuscript is now at Princeton, Scheide Library, MS 71.

The Evangeliary or Book of the Gospels is a liturgical book containing only those portions of the four gospels which are read during Mass or in other public offices of the Church. The corresponding terms in Latin are Evangeliarium and Liber evangeliorum.

Collections of ancient canons contain collected bodies of canon law that originated in various documents, such as papal and synodal decisions, and that can be designated by the generic term of canons.

Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel OSB was a Benedictine monk of Saint-Mihiel Abbey near Verdun. He was a significant writer of homilies and commentaries.

The Carolingian libraries emerged during the reign of the Carolingian dynasty, when book collections reappeared in Europe after a two-century cultural decline. The end of the 8th century marked the beginning of the so-called Carolingian Renaissance countries of Germany, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Sweden and Norway, a cultural upsurge primarily associated with church reform. The reform aimed to unify worship, correct church books, train qualified priests to work with the semi-pagan flock, and prepare missionaries capable of preaching throughout the empire and beyond. This required a comprehensive understanding of classical Latin and familiarity with surviving monuments of ancient culture.