Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early to mid-1940s in the United States. The style features compositions characterized by a fast tempo, complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerous changes of key, instrumental virtuosity, and improvisation based on a combination of harmonic structure, the use of scales, and occasional references to the melody.

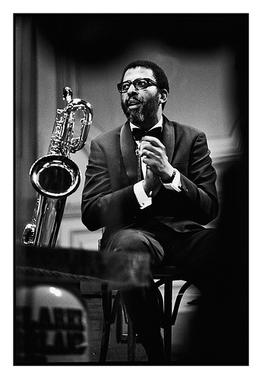

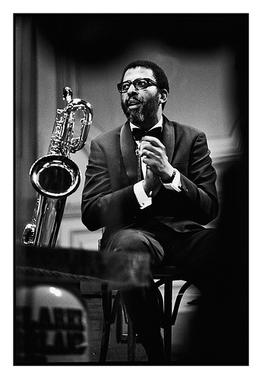

Arthur Blakey was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s.

Percy Heath was an American jazz bassist, brother of saxophonist Jimmy Heath and drummer Albert Heath, with whom he formed the Heath Brothers in 1975. Heath played with the Modern Jazz Quartet throughout their long history and also worked with Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Wes Montgomery, Thelonious Monk and Lee Konitz.

Japantown, also known historically as Japanese Town, is a neighborhood in the Western Addition district of San Francisco, California. Japantown comprises about six city blocks and is considered one of the largest and oldest ethnic enclaves in the United States.

James Edward Heath, nicknamed Little Bird, was an American jazz saxophonist, composer, arranger, and big band leader. He was the brother of bassist Percy Heath and drummer Albert Heath.

Minton's Playhouse is a jazz club and bar located on the first floor of the Cecil Hotel at 210 West 118th Street in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City. It is a registered trademark of Housing and Services, Inc. a New York City nonprofit provider of supportive housing. The door to the actual club itself is at 206 West 118th Street where there is a small plaque. Minton's was founded by tenor saxophonist Henry Minton in 1938. Minton's is known for its role in the development of modern jazz, also known as bebop, where in its jam sessions in the early 1940s, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke, Charlie Christian, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie pioneered the new music. Minton's thrived for three decades until its decline near the end of the 1960s, and its eventual closure in 1974. After being closed for more than 30 years, the newly remodeled club reopened on May 19, 2006, under the name Uptown Lounge at Minton's Playhouse, which operated until 2010, before re-opening as Minton's Playhouse in 2013.

"Hot House" is a bebop standard, composed by American jazz musician Tadd Dameron in 1945. Its harmonic structure is identical to Cole Porter's "What Is This Thing Called Love?". The tune was made famous by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker as a quintet arrangement and become synonymous with those musicians; "Hot House" became an anthem of the bebop movement in American jazz. The most famous and referred to recording of the tune is by Parker and Gillespie on the May 1953 live concert recording entitled Jazz at Massey Hall, after previously recording it for Savoy records in 1945 and at Carnegie Hall in 1947. The tune continues to be a favorite among jazz musicians and enthusiasts:

The Fillmore District is a historical neighborhood in San Francisco located to the southwest of Nob Hill, west of Market Street and north of the Mission District. The Fillmore District began to rise to prominence after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. As a result of not being affected by the earthquake itself nor the large fires that ensued, it quickly became one of the major commercial and cultural centers of the city.

"A Night in Tunisia" is a musical composition written by American trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie in 1942. He wrote it while he was playing with the Benny Carter band. It has become a jazz standard. It is also known as "Interlude", and with lyrics by Raymond Leveen was recorded by Sarah Vaughan in 1944.

John Richard Handy III is an American jazz musician most commonly associated with the alto saxophone. He also sings and plays the tenor and baritone saxophone, saxello, clarinet, and oboe.

Fillmore Street is a street in San Francisco, California which starts in the Lower Haight neighborhood and travels northward through the Fillmore District and Pacific Heights and ends in the Marina District. It serves as the main thoroughfare and namesake for the Fillmore District neighborhood. The street is named after American President Millard Fillmore.

James Moody was an American jazz saxophone and flute player and very occasional vocalist, playing predominantly in the bebop and hard bop styles. The annual James Moody Jazz Festival is held in Newark, New Jersey.

Sahib Shihab was an American jazz and hard bop saxophonist and flautist. He variously worked with Luther Henderson, Thelonious Monk, Fletcher Henderson, Tadd Dameron, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, John Coltrane and Quincy Jones among others.

"Little" Benny Harris was an American bebop trumpeter and composer.

Jivin' in Be-Bop is a 1947 musical film produced by William D. Alexander and starring Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra, which included notable musicians such as bassist Ray Brown, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, and pianist John Lewis. It also features singers Helen Humes and Kenny "Pancho" Hagood, Master of Ceremonies Freddie Carter, and a group of dancers.

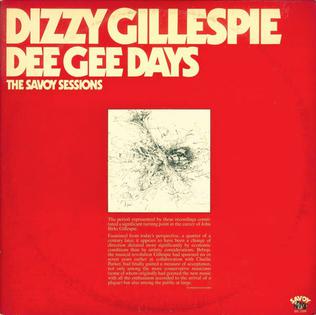

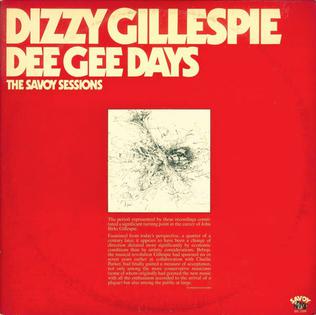

Dee Gee Days: The Savoy Sessions is a compilation album by trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie featuring performances recorded in 1951 and 1952 and originally released on Gillespie's own Dee Gee Records label. Many of the tracks were first released as 78 rpm records but were later released on albums including School Days (Regent) and The Champ (Savoy).

African Americans in San Francisco, California, composed just under 6% of the city's total population as of 2019 U.S. Census Bureau estimates, down from 13.4% in 1970. There are about 55,000 people of full or partial black ancestry living within the city. The community began with workers and entrepreneurs of the California Gold Rush in the 19th century, and in the early-to-mid 20th century, grew to include migrant workers with origins in the Southern United States, who worked as railroad workers or service people at shipyards. In the mid-20th century, the African American community in the Fillmore District earned the neighborhood the nickname the "Harlem of the West," referring to New York City's Harlem neighborhood, which is associated with African American culture.

Marcus Books, was founded in 1960, and is the oldest bookstore that specializes in African-American literature, history, and culture in the United States. For many years, it has been located in the Western Addition neighborhood of San Francisco, with a second location in Oakland, California. The store has remained independent and family-owned since its founding, and it is considered a community space for African-American and literary culture in the San Francisco Bay Area.