Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 and 1,400 °C. The strength, and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises mainly from vitrification and formation of the mineral mullite within the body at these high temperatures. Though definitions vary, porcelain can be divided into three main categories: hard-paste, soft-paste and bone china. The category that an object belongs to depends on the composition of the paste used to make the body of the porcelain object and the firing conditions.

Spode is an English brand of pottery and homewares produced by the company of the same name, which is based in Stoke-on-Trent, England. Spode was founded by Josiah Spode (1733–1797) in 1770, and was responsible for perfecting two extremely important techniques that were crucial to the worldwide success of the English pottery industry in the century to follow.

William Cookworthy was an English Quaker minister, a successful pharmacist and an innovator in several fields of technology. He was the first person in Britain to discover how to make hard-paste porcelain, like that imported from China. He subsequently discovered china clay in Cornwall. In 1768 he founded a works at Plymouth for the production of Plymouth porcelain; in 1770 he moved the factory to Bristol, to become Bristol porcelain, before selling it to a partner in 1773.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Soft-paste porcelain is a type of ceramic material in pottery, usually accepted as a type of porcelain. It is weaker than "true" hard-paste porcelain, and does not require either the high firing temperatures or the special mineral ingredients needed for that. There are many types, using a range of materials. The material originated in the attempts by many European potters to replicate hard-paste Chinese export porcelain, especially in the 18th century, and the best versions match hard-paste in whiteness and translucency, but not in strength. But the look and feel of the material can be highly attractive, and it can take painted decoration very well.

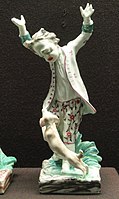

Chelsea porcelain is the porcelain made by the Chelsea porcelain manufactory, the first important porcelain manufactory in England, established around 1743–45, and operating independently until 1770, when it was merged with Derby porcelain. It made soft-paste porcelain throughout its history, though there were several changes in the "body" material and glaze used. Its wares were aimed at a luxury market, and its site in Chelsea, London, was close to the fashionable Ranelagh Gardens pleasure ground, opened in 1742.

Royal Worcester was established in 1751 and is believed to be the oldest or second oldest remaining English porcelain brand still in existence today. Part of the Portmeirion Group since 2009, Royal Worcester remains in the luxury tableware and giftware market, although production in Worcester itself has ended.

China stone is a medium grained, feldspar-rich partially kaolinised granite characterized by the absence of iron-bearing minerals. It is mainly used for making porcelain, hence the name, and coatings for paper.

Plymouth porcelain was the first English hard paste porcelain, made in the county of Devon from 1768 to 1770. After two years in Plymouth the factory moved to Bristol in 1770, where it operated until 1781, when it was sold and moved to Staffordshire as the nucleus of New Hall porcelain, which operated until 1835. The Plymouth factory was founded by William Cookworthy. The porcelain factories at Plymouth and Bristol were among the earliest English manufacturers of porcelain, and the first to produce the hard-paste porcelain produced in China and the German factories led by Meissen porcelain.

Liverpool porcelain is mostly of the soft-paste porcelain type and was produced between about 1754 and 1804 in various factories in Liverpool. Tin-glazed English delftware had been produced in Liverpool from at least 1710 at numerous potteries, but some then switched to making porcelain. A portion of the output was exported, mainly to North America and the Caribbean.

Overglaze decoration, overglaze enamelling or on-glaze decoration is a method of decorating pottery, most often porcelain, where the coloured decoration is applied on top of the already fired and glazed surface, and then fixed in a second firing at a relatively low temperature, often in a muffle kiln. It is often described as producing "enamelled" decoration. The colours fuse on to the glaze, so the decoration becomes durable. This decorative firing is usually done at a lower temperature which allows for a more varied and vivid palette of colours, using pigments which will not colour correctly at the high temperature necessary to fire the porcelain body. Historically, a relatively narrow range of colours could be achieved with underglaze decoration, where the coloured pattern is applied before glazing, notably the cobalt blue of blue and white porcelain.

The Nantgarw China Works was a porcelain factory, later making other types of pottery, located in Nantgarw on the eastern bank of the Glamorganshire Canal, 8 miles (13 km) north of Cardiff in the River Taff valley, Glamorganshire, Wales. The factory made porcelain of very high quality, especially in the years from 1813–1814 and 1817–1820. Porcelain produced by Nantgarw was extremely white and translucent, and was given overglaze decoration of high quality, mostly in London or elsewhere rather than at the factory. The wares were expensive, and mostly distributed through the London dealers. Plates were much the most common shapes made, and the decoration was typically of garlands of flowers in a profusion of colours, the speciality of the founder, William Billingsley. With Swansea porcelain, Nantgarw was one of the last factories to make soft-paste porcelain, when English factories had switched to bone china, and continental and Asian ones continued to make hard-paste porcelain.

The Bow porcelain factory was an emulative rival of the Chelsea porcelain factory in the manufacture of early soft-paste porcelain in Great Britain. The two London factories were the first in England. It was originally located near Bow, in what is now the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, but by 1749 it had moved to "New Canton", sited east of the River Lea, and then in Essex, now in the London Borough of Newham.

The Imperial Porcelain Factory, also known as the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory, is a producer of hand-painted ceramics in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It was established by Dmitry Ivanovich Vinogradov in 1744 and was supported by the Russian tsars since Empress Elizabeth. Many still refer to the factory by its well-known former name, the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory.

Saint-Cloud porcelain was a type of soft-paste porcelain produced in the French town of Saint-Cloud from the late 17th to the mid 18th century.

Chantilly porcelain is French soft-paste porcelain produced between 1730 and 1800 by the manufactory of Chantilly in Oise, France. The wares are usually divided into three periods, 1730-51, 1751-1760, and a gradual decline from 1760 to 1800.

French porcelain has a history spanning a period from the 17th century to the present. The French were heavily involved in the early European efforts to discover the secrets of making the hard-paste porcelain known from Chinese and Japanese export porcelain. They succeeded in developing soft-paste porcelain, but Meissen porcelain was the first to make true hard-paste, around 1710, and the French took over 50 years to catch up with Meissen and the other German factories.

China painting, or porcelain painting, is the decoration of glazed porcelain objects such as plates, bowls, vases or statues. The body of the object may be hard-paste porcelain, developed in China in the 7th or 8th century, or soft-paste porcelain, developed in 18th-century Europe. The broader term ceramic painting includes painted decoration on lead-glazed earthenware such as creamware or tin-glazed pottery such as maiolica or faience.

The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory was a soft-paste porcelain factory on Crown Street in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, which was active from 1757 to 1802. It mostly produced "useful wares" such as pots, teapots, and jugs, with shapes copied from silverwork or from Bow and Worcester porcelain. The factory, built on the site of an existing pottery or brick kiln, was later used as a brewery and malt kiln. Most of its remaining buildings were demolished in 1955.

Richard Champion (1743–1791) was an English merchant and porcelain manufacturer, who emigrated to the United States in 1784.