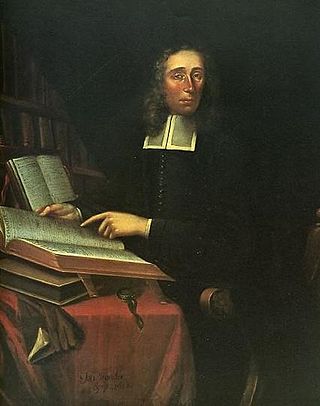

Cotton Mather was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting House in Boston, Massachusetts, where he preached for the rest of his life. He has been referred to as the "first American Evangelical".

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, nineteen of whom were executed by hanging. One other man, Giles Corey, died under torture after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in the disease-ridden jails.

Solomon Stoddard was the pastor of the Congregationalist Church in Northampton, Massachusetts Bay Colony. He succeeded Rev. Eleazer Mather, and later married his widow around 1670. Stoddard significantly liberalized church policy while promoting more power for the clergy, decrying drinking and extravagance, and urging the preaching of hellfire and the Judgment. The major religious leader of what was then the frontier, he was known as the "Puritan Pope of the Connecticut River valley" and was concerned with the lives of second-generation Puritans. The well-known theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) was his grandson, the son of Solomon's daughter, Esther Stoddard Edwards. Stoddard was the first librarian at Harvard University and the first person in American history known by that title.

Increase Mather was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the administration of the colony during a time that coincided with the notorious Salem witch trials.

Michael Wigglesworth (1631–1705) was a Puritan minister, physician, and poet whose poem The Day of Doom was a bestseller in early New England.

Sir William Phips was born in Maine in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was of humble origin, uneducated, and fatherless from a young age but rapidly advanced from shepherd boy to shipwright, ship's captain, and treasure hunter, the first New England native to be knighted, and the first royally appointed governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Phips was famous in his lifetime for recovering a large treasure from a sunken Spanish galleon but is perhaps best remembered today for establishing the court associated with the infamous Salem Witch Trials, which he grew unhappy with and was forced to prematurely disband after five months.

Samuel Parris was a Puritan minister in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Also a businessman and one-time plantation owner, he gained notoriety for being the minister of the church in Salem Village, Massachusetts during the Salem witch trials of 1692. Accusations by Parris and his daughter against an enslaved woman precipitated an expanding series of witchcraft accusations.

Bridget Bishop was the first person executed for witchcraft during the Salem witch trials in 1692. Nineteen were hanged, and one, Giles Corey, was pressed to death. Altogether, about 200 people were tried.

George Burroughs was a non-ordained Puritan preacher who was the only minister executed for witchcraft during the course of the Salem witch trials. He is remembered especially for reciting the Lord's Prayer during his execution, something it was believed a witch could never do.

Mary Webster was a resident of colonial New England who was accused of witchcraft and was the target of an attempted lynching by friends of the accuser.

Goody Ann Glover was an Irish former indentured servant and the last person to be hanged in Boston as a witch, although the Salem witch trials in nearby Salem, Massachusetts, occurred mainly in 1692.

This timeline of the Salem witch trials is a quick overview of the events.

The Bury St Edmunds witch trials were a series of trials conducted intermittently between the years 1599 and 1694 in the town of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, England.

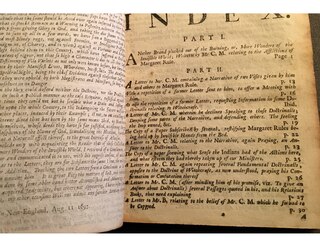

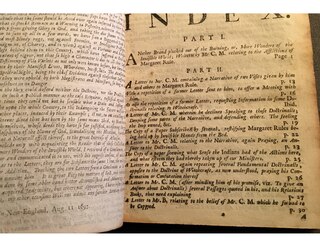

Robert Calef was a cloth merchant in colonial Boston. He was the author of More Wonders of the Invisible World, a book composed throughout the mid-1690s denouncing the recent Salem witch trials of 1692–1693 and particularly examining the influential role played by Cotton Mather.

Deodat Lawson was a British American minister in Salem Village from 1684 to 1688 and is famous for a 10-page pamphlet describing the witchcraft accusations during the Salem Witch Trials in the early spring of 1692. The pamphlet was billed as "collected by Deodat Lawson" and printed within the year in Boston, Massachusetts.

First Church in Boston is a Unitarian Universalist Church founded in 1630 by John Winthrop's original Puritan settlement in Boston, Massachusetts. The current building, located on 66 Marlborough Street in the Back Bay neighborhood, was designed by Paul Rudolph in a modernist style after a fire in 1968. It incorporates part of the earlier gothic revival building designed by William Robert Ware and Henry Van Brunt in 1867. The church has long been associated with Harvard University.

Thomas Brattle was an American merchant who served as treasurer of Harvard College and member of the Royal Society. He is known for his involvement in the Salem Witch Trials and the formation of the Brattle Street Church.

Sarah Cloys/Cloyce was among the many accused during Salem Witch Trials including two of her older sisters, Rebecca Nurse and Mary Eastey, who were both executed. Cloys/Cloyce was about 50-years-old at the time and was held without bail in cramped prisons for many months before her release.

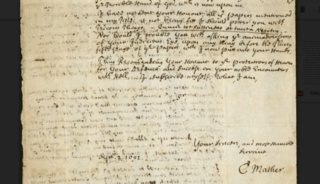

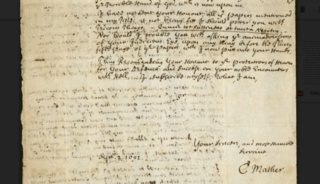

In a letter dated September 2, 1692, Cotton Mather wrote to judge William Stoughton. Among the notable things about this letter is the provenance: it seems to be the last important correspondence from Mather to surface in the modern era, with the holograph manuscript not arriving in the archives for scholars to view, and authenticate, until sometime between 1978 and 1985.